There’s arguably nobody better to lead a film production in the midst of a pandemic than the director of the movie Contagion. For that decade-old film, Steven Soderbergh had sought the insight of top epidemiologists to describe just how a pandemic starts, operates and finally ends. They described the probable start scenario as being a wet market somewhere in Asia with a bat or similar animal as the source, transferring a Coronavirus to a human host — sounds all too familiar.

When the HBO Max feature No Sudden Move got shut down from their Detroit base in March 2020, not only did Soderbergh fear for the production, he worried for his industry. Suitably armed with his Contagion research and because he just wanted to help, he started to work on the industry protocols that would allow the film business to get back to work.

Soderbergh saw that the COVID protocols he was part of could benefit others. At their core they could be applied to other businesses, or even schools. Ultimately, he was pretty proud of the fact that the resumed production of the movie never saw any positive cases.

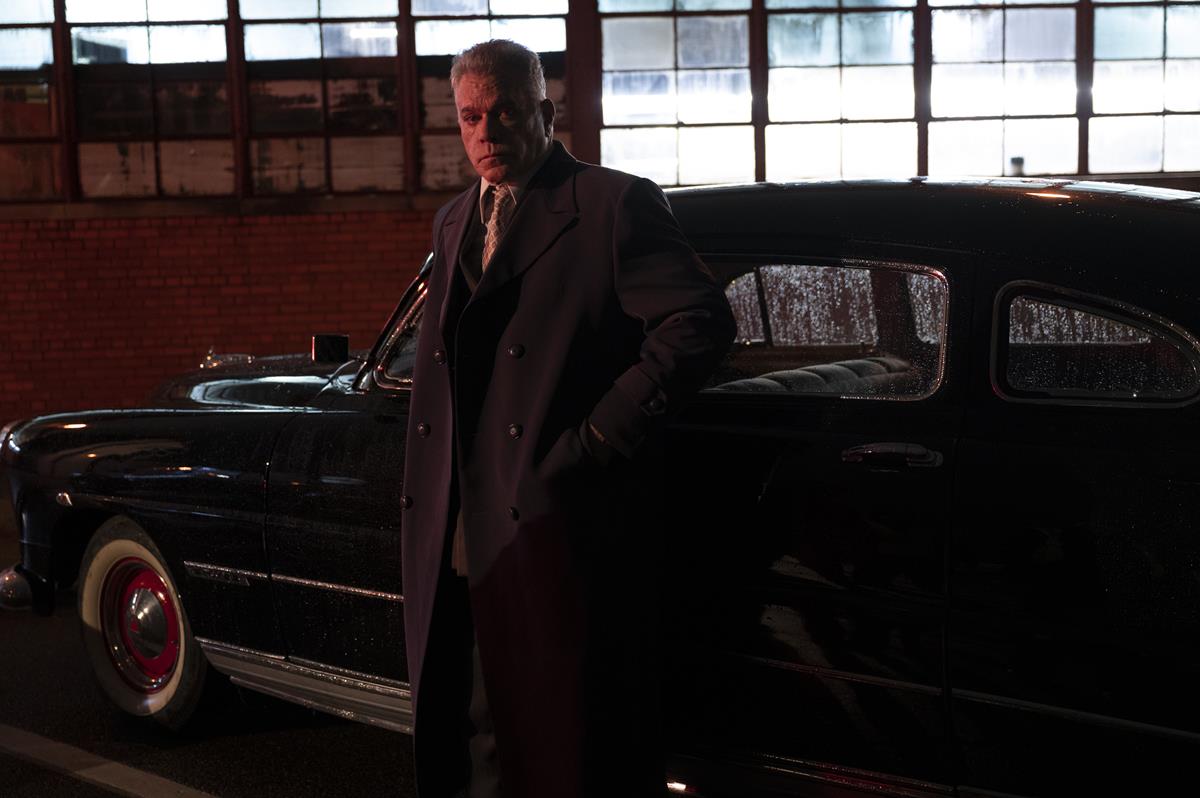

The resumption of the movie happened in October of last year and has resulted in what Variety called “An ambitious light-spirited high-twist modernist noir in the tradition of Devil in a Blue Dress and Soderbergh’s own Out of Sight.” But let’s dig a bit deeper down under the production itself.

First, a word of warning for anyone who wants a comment from Soderbergh’s director of photography. Most people will know that the credited Peter Andrews is Soderbergh himself. The name is a tribute to his late father, who shared the same first name. With this in mind, we looked for a close collaborator of his who could shed some light on what it was like working with the man, especially on the new movie.

Nat Jencks was the colorist of No Sudden Move, but has worked with Soderbergh in various creative roles since Soderbergh started shooting digitally on his film CHE. He also worked on movies from Soderbergh’s iPhone shooting phase, namely Unsane and High Flying Bird. Jencks commented with a smile in his voice about those projects, “The detour into the iPhone world was fascinating and interesting. But from my point of view as the colorist I loved the return to digital cinema cameras.”

The Grain Game

When Jencks first heard that the new Soderbergh movie was to be a fifties noir melodrama, he immediately had a ton of questions. “This was a really fun movie to work on because of the period nature of it and kind of raised some really interesting questions,” the colorist recounts. “Because with a period piece there’s a couple different aspects of it. I mean, one is you’re literally capturing that time period, you know, the costuming and everything, what’s in front of the lens. But beyond that, there are questions of the aesthetic of the time period and the sort of ethos of it, in other words what’s behind the lens… how much of what’s behind the lens, the aesthetic and the literal technology look of it should be tied to the fifties also?

“We were shooting on the RED Monstro sensor with very intense anamorphics. The lens coverage on the sensor was not entirely designed to cover the widest edges of the frame, there was very intense distortion at the far right and left edges of the frame and the initial framing had that cropped out. But when Steven saw how the optics were interacting with the image, he loved it, and was like, ‘Oh, I want to include that.’ So we actually widened out the image masking, and included those side parts, where there was very intense lens distortion. You got these really wild effects as the camera pans around bending the picture.”

— No Sudden Move colorist Nat Jencks

“You can sort of overthink these things, perhaps, and one doesn’t want to get too dogmatic about this stuff — ultimately Steven will make these choices based on what feels right — but it’s interesting to consider nonetheless… the difference between telling a story about a time period versus telling a story from that time, if that makes sense.

“On No Sudden Move, one of the things that we looked at really early on was comparing various film stocks both modern and older… one option was film emulation for Kodak early 5247 and 5248 film stock, which is of course what would have been used in that sort of early fifties era. That was an interesting time for film, it had just transitioned from the 3-strip Technicolor process to Eastman Kodak single strip process. It was the very early days of those film stocks, and that was something I was interested in exploring. But as we dug into it, we found that literal emulations of those stocks leaned towards a more muted color palette, which we didn’t feel was right for the film.

“It becomes another thought experiment… I mean some of these things are just historical accident, the aesthetic of the time certainly wasn’t going for anything muted or understated, any of the muted characteristics of those early stocks was just a limitation of those film stock at the time. In fact the earlier Technicolor 3-strip process with dye transfer prints were much richer, so this historical accident gave us this more muted color palette which wasn’t the representation of what we were going for.”

Jencks ended up using emulations of more modern reversal stocks, which had a higher saturation and color separation to really give that thick, deep, almost like a wet feel of the image. Then the discussion veered towards grain and what kind they wanted. These days you can customize that kind of thing.

“I spent a lot of time looking at grain and film grain and worked quite a bit with a company called LiveGrain. Sonny, who runs the company, was aware of the project and I talked to him about getting an actual emulation of that early Kodak 5248 film stock. He had some cans of that, and had been planning on bringing into their system eventually. They manually clean it, and do some proprietary processes to characterize the different film stocks. He pushed 5247 to the head of the queue for us and we got it just in time and liked it, which was fun. You know, those earlier film stocks were quite slow, so it actually meant that there was a little bit of a finer grain structure ASA 25, or ASA 50 something like that. The grain structure is actually much tighter than modern film stocks, which are often 200 or 400 ASA.”

LiveGrain has worked on everything from Netflix’s The King to the latest Halloween remake. It’s a proprietary and very involved piece of software which emulates film grain and texture. “Unlike a lot of grain processes, which do more of a straight overlay of a grain pattern, LiveGrain does an analysis of the image underneath and attempts to simulate what the grain would actually look like on that image based on the different color channels and how the grain would interact with those different color channels.”

The Shoot and Those Lenses

With all this talk of film stocks you might be forgiven for thinking that No Sudden Move was shot in film, but this is Soderbergh so it had to be some kind of digital capture. In fact he used the RED Monstro camera, but what was completely left field was the glass. The only lenses used on the movie were Kowa anamorphics, and they caused Jencks some interesting challenges.

“We were shooting on the RED Monstro sensor with very intense anamorphics. The lens coverage on the sensor was not entirely designed to cover the widest edges of the frame, there was very intense distortion at the far right and left edges of the frame and the initial framing had that cropped out. But when Steven saw how the optics were interacting with the image, he loved it, and was like, ‘Oh, I want to include that.’ So we actually widened out the image masking, and included those side parts, where there was very intense lens distortion. You got these really wild effects as the camera pans around bending the picture.

“There was also very intense vignetting, as well as image distortion on those lenses. That presents a unique challenge for color grading as well. In the sense that if we wanted to it would not be difficult to invert the vignette and correct for it. The same thing goes for the image distortion for that matter, but those were characteristics of the lenses that were by design and Steven loved.

“Steven was being very intentional with it. It can impact the color as, say you have a shot with Benicio Del Toro on the far left of the frame, and he’s in a vignette with that, that darkens the image significantly. Then we cut to a close-up, where he’s in the center of the image and not in the vignette. Well, do you then match the two of them so that he is the same exposure? Or do you leave it to the viewer’s brain to understand that in that first shot, when he’s in the vignette, that is not what we would call a scene referred exposure change, that it’s not that the room is darker over there, but that it’s being imposed by the lens, and that the viewer sort of understands that difference in exposure.

“You know, it’s a question, one that doesn’t have an answer, right? If we’re talking about it philosophically, I like to leave things closer to how they are in-camera; for example, say we have a front-lit shot with high contrast and then cut to someone that’s in front of a back-light from a highly exposed window behind them and it’s flaring the image, I will let it flare. As opposed to trying to bring the black level down to make the two match.

“We intuitively understand when we see that image with the flare is something optical that’s happening in camera and in fact it’s quite interesting. I think generally the same thing is true with things like vignetting. But, of course, you can talk all you want about these things, but if in the actual cut in the actual film, in the situation I describe, perhaps if you cut from someone that’s dark, because they were in a vignette to someone that’s centered in a close up, and they’re brighter, well, sometimes that feels like a jolt. So you correct it so that it flows.”

Jencks achieved a fair amount of work for No Sudden Move, but as he says, “Nothing crazy.” He’s obviously used to working with Soderbergh and says that what he gets is often a surprise. “Its always interesting. With Steven each film is truly different and its own beast.

“On this film, some of the scenes in particular were kind of like solving a puzzle in terms of color. Some had fairly complex setups in terms of the physical layout of a room or a house with great mixed lighting which of course made the image very interesting but also sometimes quite a challenge for color.

“Mixing that with the eccentric nature of the lensing created this sort of puzzle-like nature to some of the scenes. But, you know, for me, it was really fun.”

Discussion

Responses (1)