Director Lisa Immordino Vreeland may have first set out to make a movie about Truman Capote’s oeuvre, but it’s clear that fate and Hollywood had other plans.

Immordino Vreeland elected to pivot when she learned that Ebs Burnough’s “The Capote Tapes” would likely debut before she could finish her Capote documentary. To differentiate the projects, producer Mark Lee suggested that they contrast Capote with his friend, rival, and fellow gay Southerner, Tennessee Williams.

“I’d done all my research on Truman, so I put everything on the backburner and immersed myself in Tennessee’s world,” Immordino Vreeland explains.

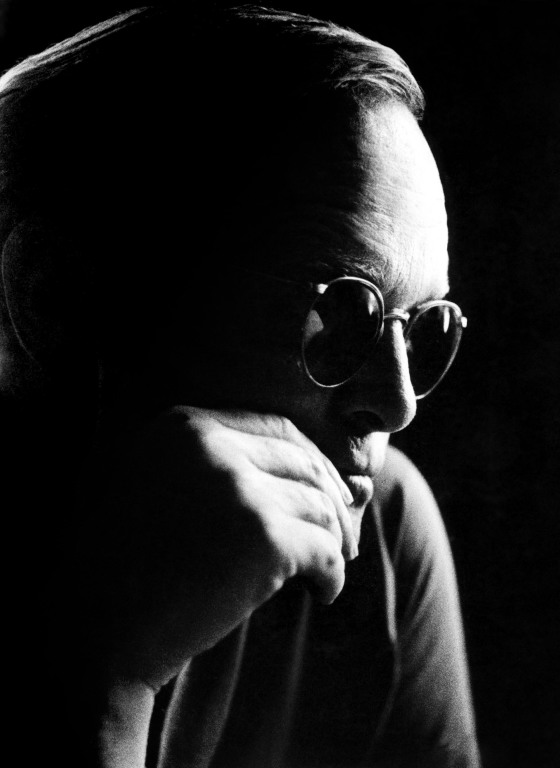

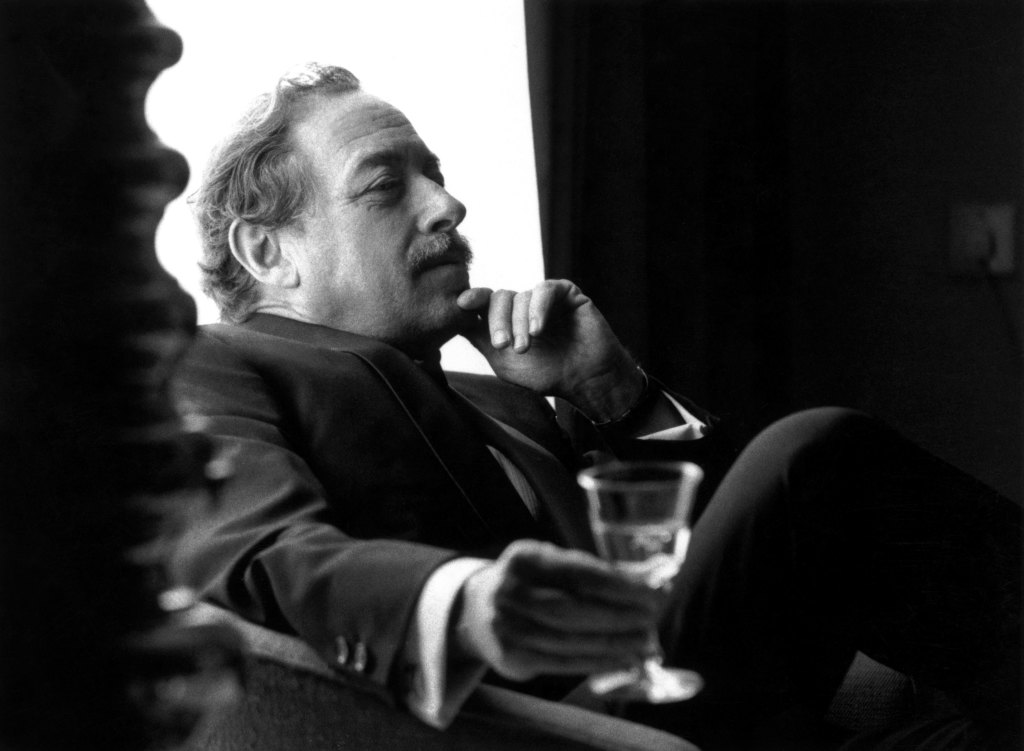

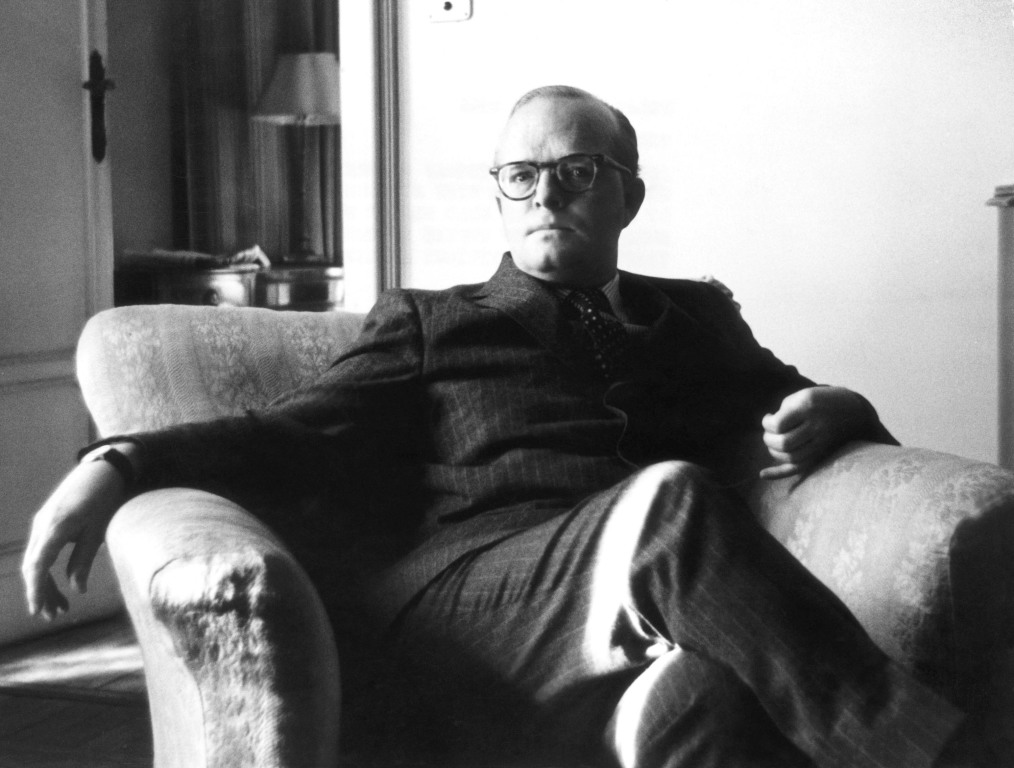

During that process, she became smitten with Tennessee Williams. Capote was certainly a larger-than-life figure (deliberately so), but Williams’ authenticity seems to have won her over.

Telling Their Own Stories

“Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation” is the rare documentary that foregoes talking heads. Instead, Immordino Vreeland clarifies she “wanted to make a movie about two writers telling their own stories, in their own words.” She did that quite literally by combining archival interviews, footage from film adaptations of their plays and books, and voiceovers from actors Jim Parsons (Capote) and Zachary Quinto (Williams).

The film is structured without chronology, as an imagined conversation in the style of Miguel Covarrubias’ 1930s Vanity Fair column. She stitches together real letters and exchanges with others in order to both illuminate their friendship and illustrate their individual career paths.

Immordino Vreeland explained the logic and structure in a Q&A with Eye for Film’s Anne-Katrin Titze. “It was so nice to focus in on a certain time, a certain relationship and be very precise about it, not having to deal with the breadth of their lives.”

She’s very clear that she aimed to create “not a biographical film, not a biopic. It’s just this intimate moment in their lives where we as the audience are dropping in on a conversation that they are having.”

That intentional intimacy and intensive research had an unintended side effect: Vreeland Immordino fell in love with one of her subjects. She tells Titze, “I really did fall in love with [William’s] written word and also as a person. There was a tenderness to him, an honesty to him. There’s something slippery about Truman Capote’s personality. He was always a mise-en-scène of himself, while Tennessee was just there. Something I understood and connected with much more.”

READ MORE: Immordino Vreeland on falling in love with Tennessee Williams (Eye for Film)

Despite very similar backgrounds as self-styled men, gay Southerners with literary ambitions and bulldogs, ultimately many of their connections were superficial. Immordino Vreeland explains they were “two very different people who often crossed paths in life,” including during some stints in Europe and through shared circles.

“When you let your subjects speak for themselves, it makes them feel more real and authentic.” Immordino Vreeland says.

A Reintroduction for the 21st Century

She believes both Capote and Williams are and will remain fixtures in the American literary canon, despite a changing place in their conversation around their work and an emphasis on the end of their lives.

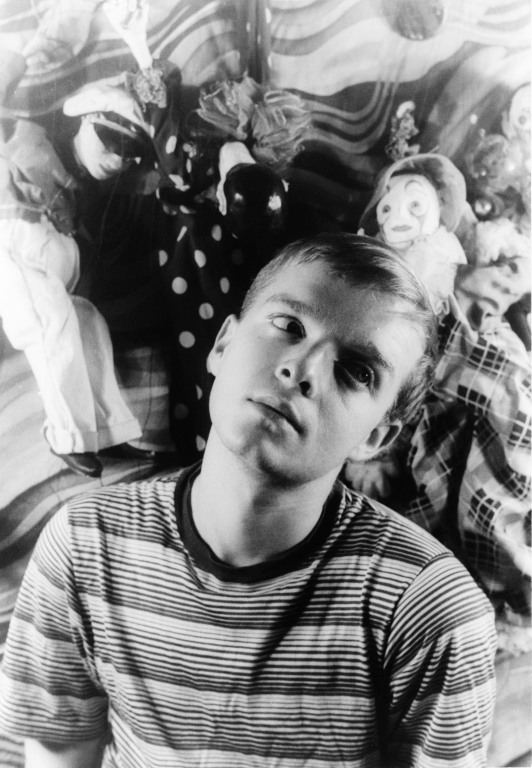

In an interview with Screen Slam, Vreeland Immordino explains, “I do feel like I have the good fortune to be able to redefine them for our generation and then really introduce them to a younger generation. I have a 19-year-old, and there’s not that much focus on these things anymore, on these people. And I think that what’s happened to both the legacy of Truman Capote and to the legacy of Tennessee Williams is that is been kind of lost in the end of their lives.”

In order to capture the deeper and less sensational aspects of these men’s lives, she emphasizes their work and writing over their public personas. “People don’t remember their words. You have to remember that they were writers.”

In terms of Capote and Williams’ significance, she says: “Their words have given this richness to American culture, and they’re never really going to disappear. They’re part of the literary imprint of America in the 20th century.”

In reminding her audience who these men were, she also creates a flow and scope for her documentary. She says, “I was more interested in constructing an entire movie around their friendship, letting these writers speak for themselves about their creativity, their process, what drove them to write, the struggles and passions of being an artist, the difficulties of trying to make a name for yourself, and maintaining that kind of success at a certain level.”

Explaining the structure of the project and its unconventional nature, Immordino Vreeland says, “I’m sure that people are going to find it kind of confusing at times, but I wanted it to be this kind of dreamscape. I think it worked. I’m not sure it would work with all subject matters.”

Jim Parsons and Zachary Quinto as Capote and Williams

Regarding Parsons and Quinto, who she tapped to animate these men, Vreeland Immordino says they are “kind of a dream team, honestly. … They were my plan A.”

In terms of her directorial vision, she explains, “We didn’t want them to sound like Truman and Tennessee. We wanted the emotions to come out of the words.”

They’re part of the literary imprint of America in the 20th century.

Lisa Immordino Vreeland

WATCH FOR MORE: Lisa Immordino Vreeland talks about her 20th century obsession (Screen Slam)

In a Zoom Q&A for Salon, Jim Parsons and Zachary Quinto share their own thoughts about authentic representation, gay friendship, and more.

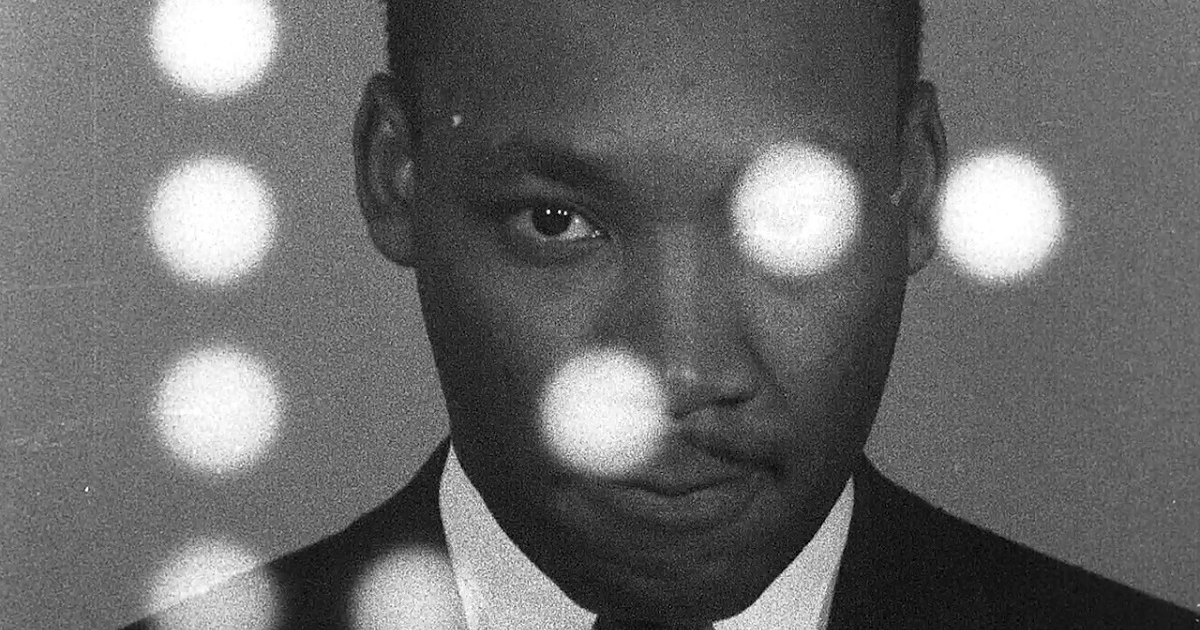

Like the authors they portray, Parsons and Quinto are both open about their lives as gay men in America. Unlike Capote and Williams, they exist in a time and space where that fact is allowed to be an element of their personas, rather than the defining characteristic.

Quinto tells Salon’s Gary Kramer: “Truman and Tennessee occupied a very specific kind of space in which they were both these incredibly flamboyant people at a time when you really only had two choices: you were either in the closet or so far at the other end of the spectrum, that there was no denying your identity. Both of these guys fall into that category. There was an edge to that at the time; they both were in relationship to, and that edge informed their relationship to one another.”

This role was not the first opportunity for Quinto to tackle Williams’ complexities. Nearly a decade earlier, Quinto portrayed him for a Broadway revival of “Glass Menagerie” opposite Cherry Jones. He drew on that experience, as well as Immordino Vreeland’s extensive research.

Of Williams and that Broadway production, Quinto says, “He is a singular voice who processed his own traumas. I always felt that Tennessee was at once chasing something and running from something, all the time in his writing and his work. And playing his most autobiographical character in his most autobiographical play, I really felt connected to him and his lineage in a way that made me feel this was an organic progression.”

Parsons also came into this project with affinity for Williams. He tells Kramer, “I knew Tennessee very well from seeing and reading and watching movie versions of his plays. I had also read the John Lahr biography, which was just sensational. The only thing I knew about Capote were two films … He was very new to me as far as his writing.”

Both Quinto’s and Parsons’ preexisting esteem for Immordino Vreeland is also clear from this Q&A.

Parsons says documentaries about art and artistic types are his favorite films to watch, and he was an admirer of Immordino Vreeland’s work before this project. “I was not only a fan of the movies Lisa had made, but also movies like that.”

For his part, Quinto says Immordino Vreeland “brings this incredible insight into iconic people and really humanizes them and brings an audience into their sphere of influence with an effortless intellect and emotional thread.”

Speaking of threads, Quinto says the experience enabled him to learn about the writers’ relationship as Immordino Vreeland intended. “There’s a kind of prickly playfulness that exists between them that captures something ephemeral and carries it through the intervening decades since they’ve been gone. I love that about” the film.

READ MORE: Parsons and Quinto dish on their friendship, playing and reading literary rivals (Salon)

Whether or not Immordino Vreeland succeeds in her vision for an intimate conversation relies, perhaps, on the viewer’s imagination and understanding of the subjects as much as the editing and structure of the film.

Reviews and Critiques

The Guardian does not quite pan the documentary but concludes that its premise is not entirely successful. David Smith writes that Immordino Vreeland starts with a “shaky premise and never quite joins the dots.”

He backs up his assertion with an assessment from Williams’ biographer John Lahr, who argues the documentary does not live up to its name (“An Intimate Conversation”): “It made no case. There’s no conversation. It looked meaningful but it had very little content. It didn’t explore the psychologies of either man.”

Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw writes, “The film simply places Capote and Williams alongside each other as if in a diptych.”

READ MORE: Is Immordino Vreeland’s latest film a successful in its talking-head free form? (The Guardian)

Neither Capote nor Williams ought to be defined by the Hollywood films that came of their work, and yet, the documentary is obliged to lean on their movies over the books or plays.

Peter Debruge, The Guardian

Variety’s review finds fault with a thornier aspect of the film: reliance on others’ interpretations of Capote and Williams’ work.

Peter Debruge writes, “Neither Capote nor Williams ought to be defined by the Hollywood films that came of their work, and yet, the documentary is obliged to lean on their movies over the books or plays.” This is both a criticism and an acknowledgment of the constraints of her chosen art form and the materials available from that period.

Additionally, Debruge observers that “unlike Immordino Vreeland’s previous subjects, Capote and Williams were wordsmiths, not visual artists, which makes them harder to represent on-screen. As such, the resulting project feels better suited to book form than that of a feature-length movie.”

Unfortunately for Vreeland, the type of book to which Debruge compares her film to is less instructive biography and more casual enthusiast’s collectible. “It’s a pleasure to spend an hour and a half in the resurrected company of these two intellects, but the experience feels like the lazy alternative to reading biographies about either man, while the iMovie-style editing strategy of slow-fading between layers of old photographs makes them feel like ghosts of a long-forgotten past.”

NOT WHODUNNIT, BUT HOW-DUNNIT — DIGGING INTO DOCUMENTARIES:

Documentary filmmakers are unleashing cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality to bring their projects to life. Gain insights into the making of these groundbreaking projects with these articles extracted from the NAB Amplify archives:

- Crossing the Line: How the “Roadrunner” Documentary Created an Ethics Firestorm

- I’ll Be Your Mirror: Reflection and Refraction in “The Velvet Underground”

- “Navalny:” When Your Documentary Ends Up As a Spy Thriller

- Restored and Reborn: “Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)”

- It WAS a Long and Winding Road: Producing Peter Jackson’s Epic Documentary “The Beatles: Get Back”

READ MORE: Is “Truman & Tennessee” more coffee table book than conversation? (Variety)

iNews UK’s James Mottram differs in his assessment. He writes, “It is a great shame that neither Truman Capote nor Tennessee Williams are around to witness Lisa Immordino Vreeland’s new documentary about them. Forced to share equal billing, the looks on their faces would surely be priceless. But these friends and rivals are both beautifully served in a film that brings them vividly back to life.”

READ MORE: Why Immordino Vreeland’s latest film is innovative (iNews UK)

“Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation” premiered at the Venice Film Festival last year and was selected for the 2020 Telluride Film Festival. It is now playing in select theatres and is also available to watch online via Kino Marquee.