Are film and TV dramas that play out entirely on a computer screen any more than a gimmick? The mastermind behind global horror smash Unfriended and new feature Profile believes he has helped create a new genre — and Hollywood agrees.

“From video chatting to texting, to sexting, our modes of living and loving have become inseparable from different types of screens — computers, phones, tablets,” says Timyr Bekmambetov. “And if our stories hope to stay true, I believe they must move on as well.”

Last year, with all our lives gone digital, Universal inked a deal to partner with the Kazakh-Russian filmmaker on five new features to be made in what Bekmambetov calls his Screenlife format.

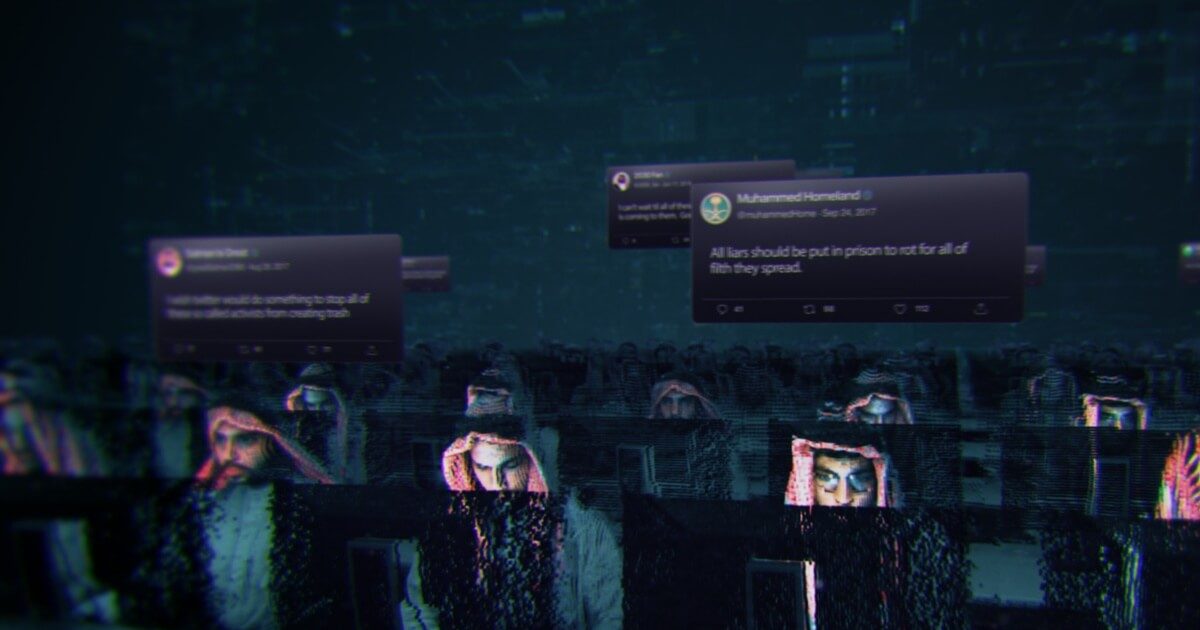

In a Screenlife film, viewers see the action play out from the POV of the computers, tablets and smartphones used by the characters.

He founded the tech startup Screenlife Technologies to develop products based on AI and deep learning for the mass production of Screenlife content. The technique has earned Bekmambetov’s Bazelevs production company a place in Fast Company’s Top 10 Most Innovative video companies in the world.

The format’s debut was 2014 teen horror Unfriended, which Bekmambetov produced for director Levan Gabriadze. When the $1 million budgeted movie was picked up by Universal and went on to make $65 million, spawning a sequel in 2017, it made people forget the critical and commercial aberration that was the director’s last studio outing — a 2016 remake of Ben Hur.

“I think we were a little bit ahead of the time with Screenlife. COVID really changed the world. Now, no one has the question, do we need Screenlife? It is a way to talk about us, our civilization, our lives, our wishes, everything, that traditionally we can’t always capture.”

— Timyr Bekmambetov

“When you’re making a movie for over $100 million, there are a lot of scared people,” Bekmambetov told Slashfilm. “You feel a responsibility. You don’t have a lot of freedom. 99% of movies are made by a collective brain and made by formulas. With Screenlife, because it’s not expensive, you can make your own choices.”

He continues, “With traditional movies, you have the script, the shoot, and the edit. You can change, but you can’t change too much. Until the last second with Screenlife, you can alter or change the whole story. It is one of the biggest changes.”

Over the last forty years, as digital communications have taken over more of our lives, filmmakers have wrestled with how to show it on screen. Looking over the shoulder of the actor as they type into the internet on PC or phone and receive an answer immediately dates the film because the technology goes out of date so quickly and it can also be a dramatic black hole. It’s not cinematic.

READ MORE: ‘Profile’ Director Timur Bekmambetov Believes Screenlife is the Future of Cinema (Slashfilm)

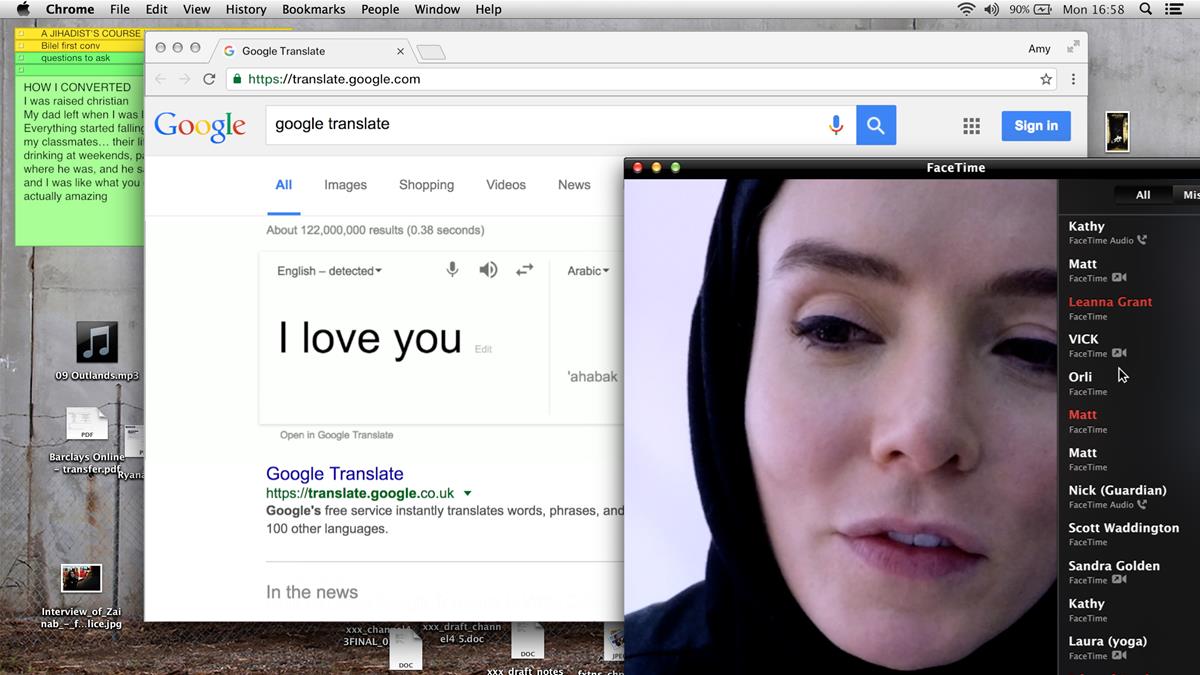

Screenlife, on the other hand, can show the inner life of the character. Bekmambetov contends, “From what you see on the screen, you can get a sense of a character. Like, if somebody is looking up how to buy a cheap dog, you can assume he’s probably lonely. It takes 10 seconds to show he’s lonely rather than minutes in traditional filmmaking.”

A Screenlife Production in “Profile”

Bekmambetov’s latest film, actually made in 2018 but given theatrical release by Focus Features last month, shows the development of his thesis, not least in its subject matter.

Profile is inspired by the 2015 nonfiction bestseller “In the Skin of a Jihadist” by a French journalist who now has round-the-clock police protection and has changed her name to Anna Erelle.

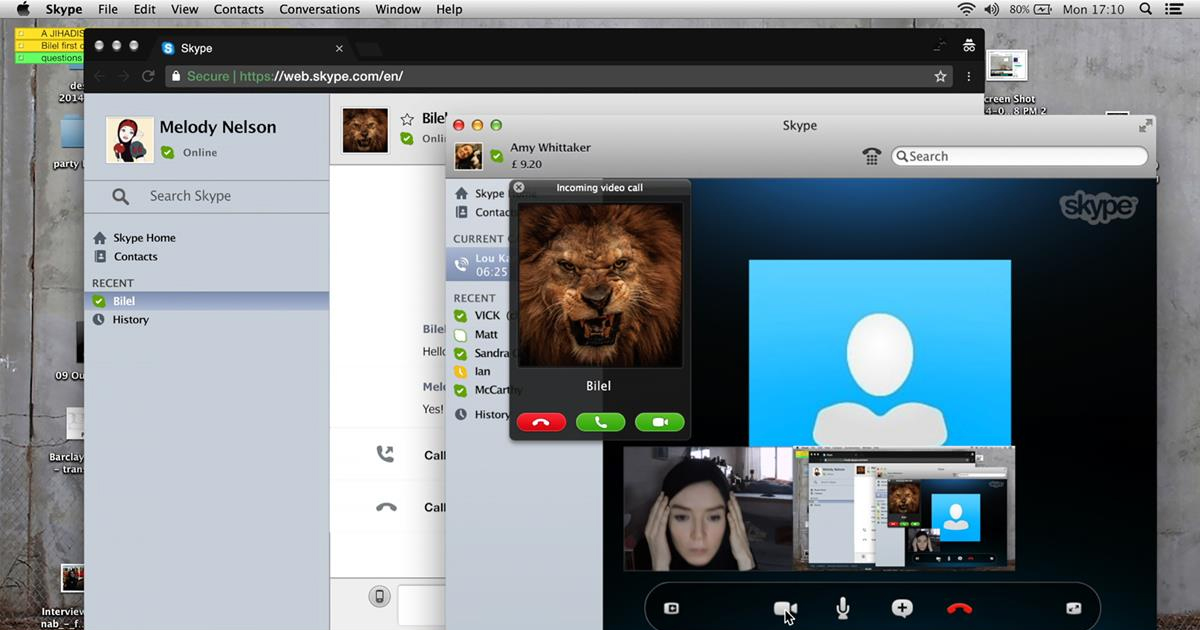

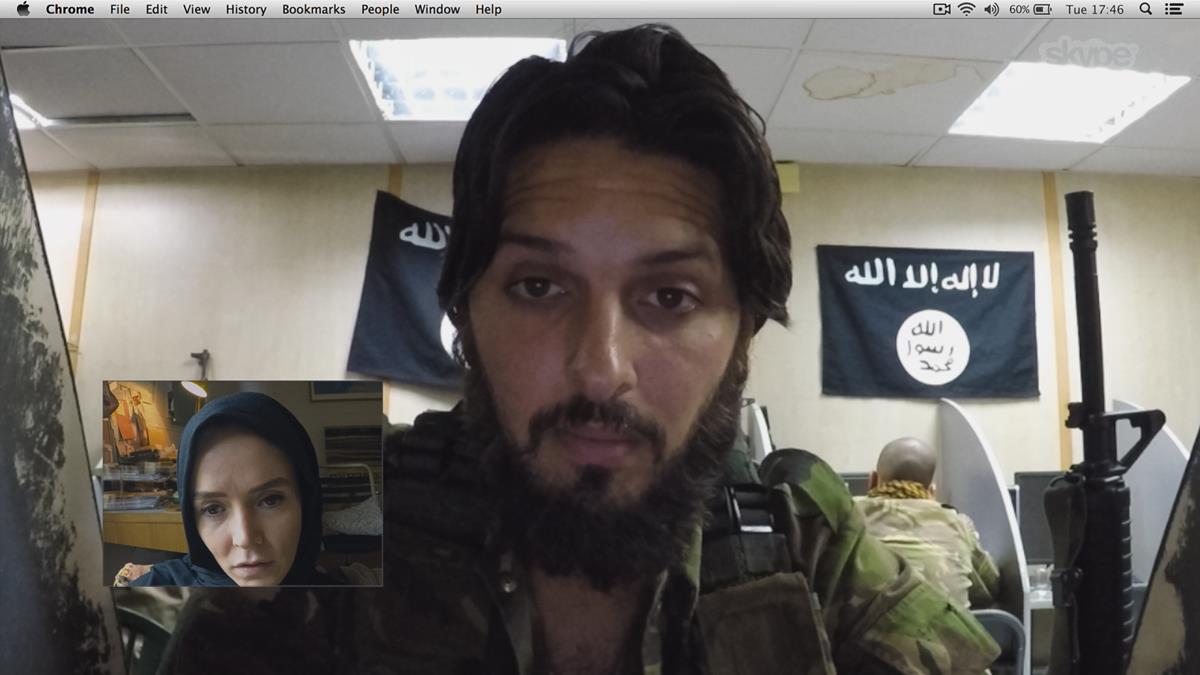

In the film, the journalist character Amy Whittaker (Valene Kane) creates a fake Facebook account to ensnare a jihadist and moments later is fielding friendly messages from Abu Bilel (Shazad Latif), a London-born militant who is eager to connect with the young woman who reposted his videos.

“The first movies [including Unfriended] were almost like animated movies, because all these motion designers created the rhythm and the choreography,” Bekmambetov explains to Moviemaker Magazine. But with the Screenlife software that Profile was created within, the actors themselves are performing all of the computer movements — whether executing a Google search or chatting with one another — in real time.

“The uniqueness of Profile is that we created the real folders and real environment and the actors did it themselves,” Bekmambetov says. “We recorded their faces and their behavior and their manipulation with the screen at the same time. This is what is revolutionary for Screenlife.”

So when actor Kane, Skypes with the terrorist, while also simultaneously text chatting with her boyfriend or her boss, she does not have to pretend to be multitasking. She really is performing those simultaneous actions during the sequence. According to Bekmambetov, this leads to more natural performances and also gives space for the actors to improvise.

READ MORE: Profile Director Timur Bekmambetov Tells Intimate Stories Onscreen — Computer Screens (MovieMaker Magazine)

Taking the specific Screenlife format of Profile into account, Bekmambetov made the unorthodox choice to cast the film entirely online, via taped submissions and Skype.

“It was important to see how actors would look on a computer screen,” he explains in the film’s production notes. “I decided to cast actors without meeting them in person because that’s how the audience will see them.”

Once the field of candidates was winnowed down, casting director Jon McClary arranged Skype readings for pairs of actors, as well as Skype meetings with Bekmambetov and the individual actors.

“The uniqueness of Profile is that we created the real folders and real environment and the actors did it themselves. We recorded their faces and their behavior and their manipulation with the screen at the same time. This is what is revolutionary for Screenlife.”

— Timyr Bekmambetov

Rehearsals were unconventional too. Since the characters’ Skype conversations would take place in real time, without cuts, Bekmambetov says, “the actors needed to be able to play that whole time in close-up… to rehearse it like a play in the theatre.”

Once production got underway, the actors were deliberately separated to simulate the distance between their characters. Kane would stay in London, and Latif would travel to Cyprus, where Bazelevs has a production office and a local team that could organize the innovative shooting process.

Explains Bekmambetov, “I wanted Val and Shazad in two different countries, far from each other, to make their communication process feel absolutely real: Skyping with each other, suffering from sound issues and screen glitches. And Cyprus had the right look for the Middle East.”

The production rented a house in London for the 10 days of shooting, with Bekmambetov directing the shoot from the ground floor. The first floor was the set for Amy’s flat.

The Screenlife shooting process requires different tools, techniques and technology than traditional movies. Rather than filming the actors with cameras in three-dimensional space, the format calls for recording screens, be it that of a computer, iPhone or tablet.

For Profile, GoPros were mounted on the back of a given device and fixed as close as possible to the device’s built-in camera to reproduce that camera’s angle. Some devices had a microphone mounted on the back as well.

Because the cast members were the ones using the devices, actors became their own cinematographers. Bekmambetov gave the cast directions about manipulating their devices, emphasizing naturalism.

“I explained to the actors that they shouldn’t overthink the composition of the shot,” Bekmambetov says. “They needed to move computers and phones organically. We all know how to make Instagram photos, we know how to shoot ourselves. The actors could compose their shots because they do it in real life, too.”

“From video chatting to texting, to sexting, our modes of living and loving have become inseparable from different types of screens — computers, phones, tablets.”

— Timyr Bekmambetov

While traditional camera rigs weren’t necessary, a traditional, well-equipped sound station was a must for recording in Amy’s flat. A special microphone was attached to Kane’s laptop to record the interaction of fingers and keys, typing and clicks. A separate microphone recorded voices.

Kane had a host of activities to manage on her laptop: typing, Skyping, Facetiming, messaging, opening document files, Googling, watching videos, and more. “It took a little time to settle into the process. It was a completely different way of working, typing something to the computer while you’re staying in character. You’re really watching videos, which does inform the work you’re doing, but you also have to do everything within a certain amount of time.”

Bekmambetov argues that a traditional filmmaking approach to this true story wouldn’t have worked. “The whole story happens in the digital space,” he tells MovieMaker. Showing two people sitting in the rooms and chatting with each other is an unfeasible pitch. But it works in Screenlife, he adds, “as soon as you see the screens, then it’s a drama, it’s a thriller, it’s a romance.”

Some critics agree: It was garlanded with awards at the Berlin Film Festival and SXSW.

Screenlife Multiplies

Berkmambetov is no ingénue. He broke out with Russian fantasy epics Night Watch (2004) and Day Watch (2005) and made his directorial debut in Hollywood with the blockbuster Wanted (2008) starring Angelina Jolie and Morgan Freeman. He also produced the startling POV action thriller Hardcore Henry, but it is Screenlife projects that are now filling up his IMDB page.

Following Unfriended he produced Searching (2018), a mystery thriller directed by Aneesh Chaganty in Screenlife and starring John Cho, which raked in $75 million.

In 2019, he produced a 10-episode original series Dead of Night for Snapchat, with the story revolving around a viral outbreak that turns people into zombies. It scored with more than 14 million unique viewers in the first month of release and got extended for the second season.

“When you’re making a movie for over $100 million, there are a lot of scared people. You feel a responsibility. You don’t have a lot of freedom. 99% of movies are made by a collective brain and made by formulas. With Screenlife, because it’s not expensive, you can make your own choices.”

— Timyr Bekmambetov

Earlier this year, Berkmambetov’s Screenlife production R#J premiered at Sundance and won a special prize at SXSW. It retells Shakespeare’s classic tale of forbidden romance, Romeo and Juliet, through texts, FaceTime, and other social media touches.

At SXSW he also presented iBible, a Screenlife rendition of the Book of Genesis, with God speaking with the voice of Morgan Freeman and using a smartphone to create the universe.

He’s in collaboration with Sony Pictures on a follow up to Searching and with MarVista on a new YA drama #fbf starring Ashley Judd and CreeCicchino.

“I think we were a little bit ahead of the time with Screenlife,” Berkmambetov tells Slashfilm. “COVID really changed the world. Now, no one has the question, do we need Screenlife? It is a way to talk about us, our civilization, our lives, our wishes, everything, that traditionally we can’t always capture.”

Discussion

Responses (1)