When Sir Roger Deakins talked to No Time To Die director of photography Linus Sandgren about shooting Bond, they both agreed that it had specific challenges. “It’s like the ultimate challenge of your own abilities. You have to learn how to work on these types of production,” Sandgren said to a sagely nodding Deakins.

In a way Sandgren had been preparing for Bond for most of his life. The old films had inspired him to play like the British spy when he was a boy and then learn to scuba dive when he was a teenager. When the offer came in to shoot the 25th film of such an illustrious and international series, he was flattered but ready.

But the history of Bond wasn’t the only thing that persuaded him to accept the challenge. “Also I was very interested in Cary Joji Fukunaga the director, from his work. I felt that in our initial chat we connected on so many levels in regards to how he wanted to make this film and in regard to how he looked at films in general,” the DP said.

“He’s not afraid of following the script in the direction that he feels the script needs to go. His films looks very different, they’re very different types of films but there’s definitely a strong filmmaker behind them.

“He wanted Bond 25 to be an epic cinematic journey, both adventurous and emotional, that would make audiences close their eyes in fear, laugh and cry. To me, that is exactly what a Bond movie should be.”

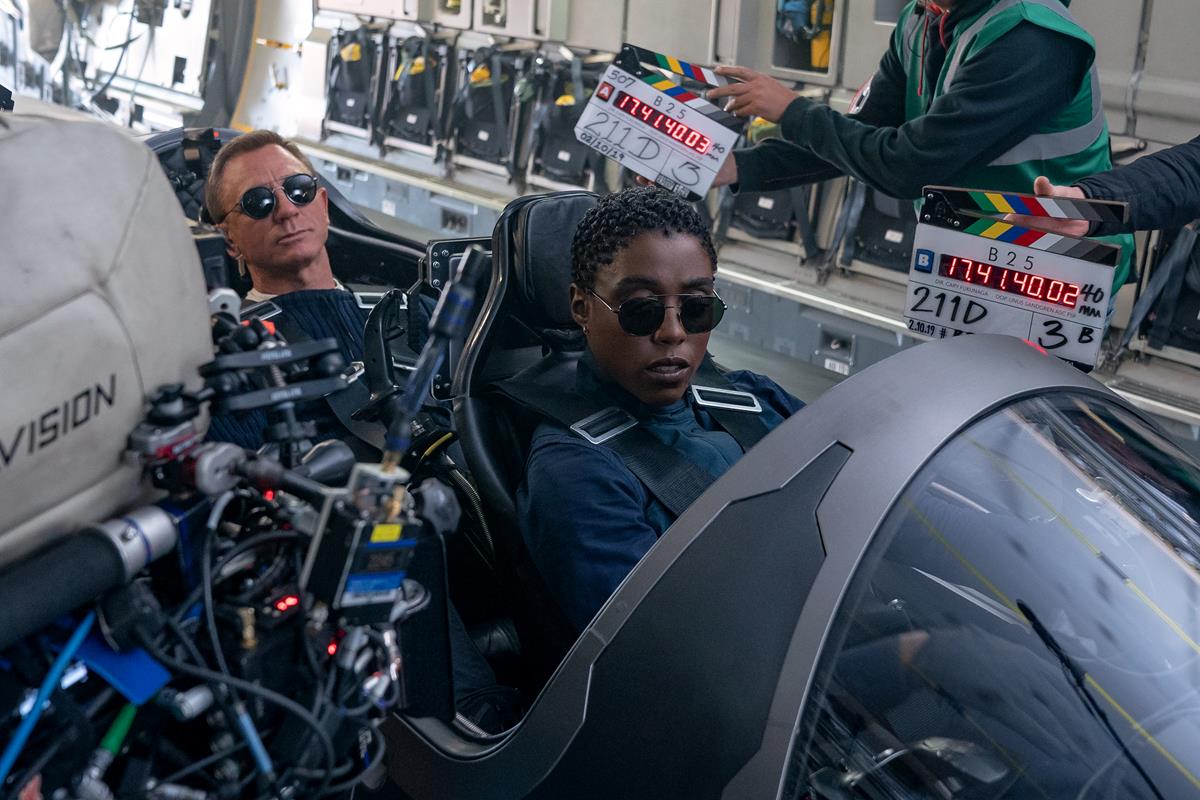

Sandgren told IBC 365 about Bond’s new purpose with the accent on the emotional notes, “We wanted to combine the legacy of action, glamour and escapade at the heart of Bond with the more intimate and emotional version played by Daniel in our storytelling.”

READ MORE: Shooting Bond: Behind The Scenes of No Time To Die (IBC 365)

Fukunaga had had his eye on Sandgren, too, as he told American Cinematographer. “I’d seen a few of Linus’ films, but it was his visceral work on First Man that made me think he’d be perfect for Bond,” Fukunaga said. “I liked how he pulled off a mixture of highly technical cinematography and simple but elegant lighting approaches to night exteriors and interiors.”

American Cinematographer goes on to explain how film was the only capture choice for No Time To Die. “The production was captured on a combination of 35mm and 65mm film negative. The filmmakers wanted smooth transitions between the two gauges, so entire sequences were designed for one format or the other, with no intercutting.

“The production was shot mainly on Kodak Vision3 500T 5219, though Vision3 250D 5207 and 50D 5203 were employed as well, the latter specifically for 35mm-captured day exteriors. The crew shot 1,007 rolls of 35mm — and more than 1.7 million feet of 35mm and 65mm total.”

The majority of the picture was captured in anamorphic 35mm — which Sandgren regarded as “the classic Bond format” — with Panavision’s Panaflex Millennium XL2 camera.

“Film is much more colorful [than digital] and it always gives me joy to get the negative back slightly enhanced by the processing of the film itself,” Sandgren explained. “When you watch this film in IMAX you don’t see the edge of the frame. There’s more of the picture above your head, below your feet as if you’re inside the helicopter, inside the movie.”

After much testing, Sandgren chose Panavision G Series Anamorphic Primes for the Panaflex Millennium XL2. “We shot some tests, and wow, how they performed!” Said Sandgren. “They’re fast and sharp, and I learned to love them more than the Cs. They’re beautiful and gentle but with lively, soft flares.”

READ MORE: Rehired Gun: No Time to Die (American Cinematographer)

Fukunaga was a G Series fan too, “I love Panavision anamorphics. I’d had more experience with the C and E series, so I was interested to see how the G Series performed in the variety of dark and light sets we had.”

With Sandgren extolling the virtues of the IMAX format, it was up to A-camera/Steadicam operator Jason Ewart and B-camera/Steadicam operator Ossie McLean to handhold the IMAX cameras. “Those cameras are a lot heavier and quite awkward to operate,” Ewart says. “They weren’t designed for action sequences. We did quite a lot of handheld with them, which was challenging, to say the least. Their size and weight took a lot of getting used to, and it was physically demanding to follow these fast-paced fight and action scenes.”

Camera moves called for varying degrees of planning, as Fukunaga explained. “Some moves were thought about ahead of time,” he adds, “certainly for action scenes and scenes that needed previs, but for the most part, the actors, Linus and I would [map] out the camera positions once the blocking had been set.”

“Sometimes a simple, intimate, handheld shot was much better than a dramatic crane shot,” Sandgren added. “The range in this film is as wide as it can be!” One notable crane shot featured in a scene where Bond, showing up at a Spectre party in a dark ballroom, is revealed by a spotlight to be surrounded by unfriendly figures. The first portion of the scene was covered on Steadicam and dolly as Bond moves about, and then a high-angle setup revealed the sea of opposition he faces.

At the end of the long shoot with various delays, the director was generous with his praise for Sandgren, “Linus is one of the most supportive collaborators you could find,” Fukunaga said. “Inevitably, time and budget constraints weigh down on creative choices, and when I was at the point of bending to compromise, Linus would stand up with his persuasive smile and his laser focus on the end result, and say, ‘Well, you could do it the right way or you could do it the wrong way.’”

In preparation for shooting No Time To Die, Sandgren and his team traveled to the IMAX headquarters for a viewing party to get a feel for the format and what it can achieve.

“We watched films in IMAX, both shot, digitally projected in IMAX and then on film, and we saw 3D films that had shot stereoscopic IMAX,” he recounted to Collider’s Steve Weintraub:

“Incredible underwater footage, it’s just insane how they made these movies with two IMAX cameras connected. Now there’re cameras with two rolls of 65 waiting for fish to eat something and then capture that, so that was pretty insane. We watched a bunch of things at IMAX to see what happens when the format opens up and how to actually frame for IMAX, and how to compose for IMAX, and how the frame opens up when you get into IMAX sequences.”

Sandgren had shot in IMAX on First Man, and had learned a great deal from the experience, but that was only for a single sequence of the Moon landing, and he was still somewhat daunted by the idea of using the unwieldy IMAX cameras throughout the entire shoot.

“In the beginning, it may have been a little more daunting to work with that sort of big camera. Then I think it was interesting because we ended up deciding, which I think is the right [way] to do IMAX, is to frame for the middle of the frame or 2:40:1, that’s your composition,” Sandgren recounted. “So that it actually is very easy to shoot it in a combined format, or it’s going to go 2:40:1 for release and a lot of the image is cropped out, but it’s still, you frame, compose for 2:40:1, just have to make sure the equipment and lighting and stuff can’t be in the rest of the image.”

LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION! SPOTLIGHT ON FILM PRODUCTION:

From the latest advances in virtual production to shooting the perfect oner, filmmakers are continuing to push creative boundaries. Packed with insights from top talents, go behind the scenes of feature film production with these hand-curated articles from the NAB Amplify archives:

- Savage Beauty: Jane Campion Understands “The Power of the Dog”

- Dashboard Confessional: Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s “Drive My Car”

- “Parallel Mothers:” How Pedro Almodóvar Heralds the New Spanish Family

- “The Souvenir Part II:” Portrait of the Artist As a Young Woman

- Life Is a Mess But That’s the Point: Making “The Worst Person in the World”

The DP estimates that the finished film contains between 40 and 50 minutes of IMAX footage. “One challenge was also, the DB5 car was so small,” he said. “Putting an IMAX camera on, it really changed the balance of the car. You had to put two cameras on. It was better to two cameras on at the same time. We had these stunts scenes where two IMAX cameras on that little DB5 in order to just actually keep it balanced. Then we’ve got two shots in the same setup, so that was pretty good.”