TL;DR

- To what extent will AI impact elections worldwide? One camp warns of AI leading to a deluge of misinformation, especially on social media. The other finds the fears largely overblown, pointing to research indicating that AI may lead to more misinformation during elections, but with little effect.

- While misinformation has always been a feature of politics, reports say, the relatively easy-to-use AI technologies risk increasing the scale and quality of false content that might circulate online.

- Time is running out for more research, for legislative guardrails, and for technology counter measures: “It’s the ‘red queen problem’ — we run as fast as we can to stay in the same place.”

READ MORE: Elections and Disinformation Are Colliding Like Never Before in 2024 (The New York Times)

Experts fear 2024 could be the year a viral undetectable deepfake has a catastrophic impact on an election. An estimated 2 billion people, or around half of the world’s adult population, are expected to head to the polls in 2024, including in the US, the EU, India and the UK.

“Almost every democracy is under stress, independent of technology,” Darrell M. West, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution think tank told The New York Times. It is, he said, a “perfect storm of disinformation.”

However, recent academic research on online misinformation suggests multiple reasons why we might want to be cautious about overhyping the future impact of AI-generated misinformation.

The NYT lists dozens of national elections to be held this spring, including in India, where the prime minister has warned about misleading AI content. Elections for the European Parliament will take place in June as the EU continues to put into effect a new law meant to contain corrosive online content. A presidential election in Mexico, also in June, could be affected by a feedback loop of false narratives from elsewhere in the Americas.

The US, of course, already in the thick of a presidential race marked by resurgent lies about voting fraud, goes to the polls in November.

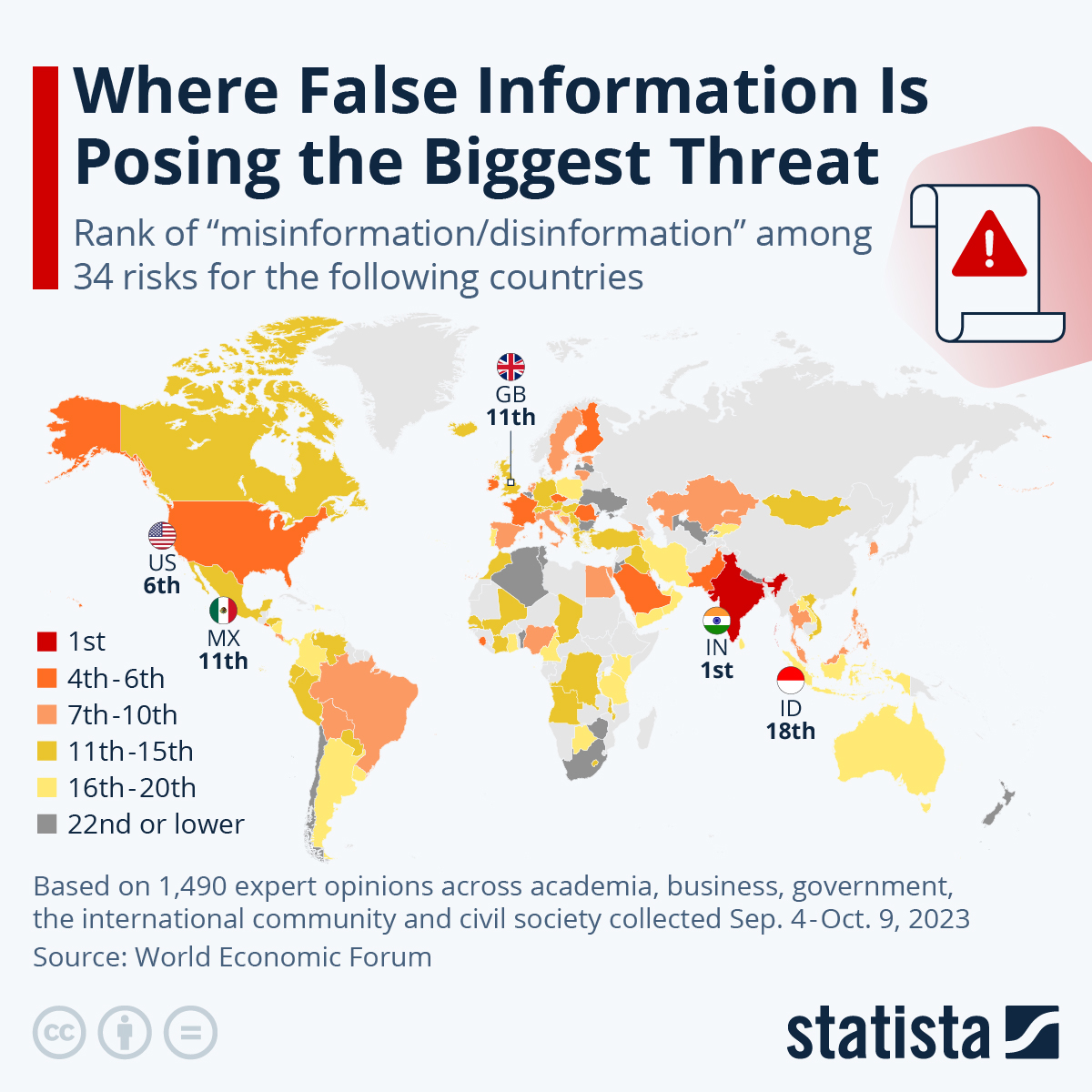

A chart from Statista based on the World Economic Forum’s 2024 Global Risk Report, above, shows the varying degree to which misinformation and disinformation are reckoned to be problems for various countries over the next two years.

“AI technologies reached this perfect trifecta of realism, efficiency and accessibility,” Henry Ajder, an expert on AI and deepfakes and adviser to Adobe and Meta, tells Hannah Murphy at the Financial Times. “Concerns about the electoral impact were overblown until this year. And then things happened at a speed which I don’t think anyone was anticipating.”

The political establishment in many nations, as well as intergovernmental organizations like the Group of 20, appears poised for upheaval, Katie Harbath, founder of the technology policy firm Anchor Change told the NYT. Disinformation — spread via social media but also through print, radio, television and word of mouth — risks destabilizing the political process. “We’re going to hit 2025 and the world is going to look very different,” she said.

The threats range from enemy states seeking to discredit democracy as a global model of governance to internal rogue political actors intent on sowing false narratives. Then there are those that are merely trying to generate engagement and profit, through advertising clicks for example. There are also secondary effects.

In politics, candidates now have the “ability to dismiss a damaging piece of audio or video,” Bret Schafer, a propaganda expert at the Alliance for Securing Democracy, says to the Financial Times. The concept, known as the “liar’s dividend,” was first outlined in a 2018 academic paper arguing that “deepfakes make it easier for liars to avoid accountability for things that are in fact true.”

Some experts worry that the mere presence of AI tools could weaken trust in information and enable political actors to dismiss real content. One study found news coverage around fake news has lowered trust in the media, and there is evidence this is already occurring with AI. A recent poll, for example, found that 53% of Americans believe that misinformation spread by AI “will have an impact on who wins the upcoming 2024 U.S. presidential election,” despite the fact that as yet there is no evidence to suggest this is the case.

READ MORE: The rising threat to democracy of AI-powered disinformation (Financial Times)

Others say fears, for now, are overblown. AI is “just one of many threats,” James M. Lindsay, SVP at the Council on Foreign Relations told The New York Times. “I wouldn’t lose sight of all the old-fashioned ways of sowing misinformation or disinformation,” he said.

On the other hand, artificial intelligence “holds promise for democratic governance,” according to a report from the University of Chicago and Stanford University quoted in the NYT. For example, politically focused chatbots could inform constituents about key issues and better connect voters with elected officials.

Which is correct? Drawing on a decade of research on the relationship between social media, misinformation, and elections, The Brookings Institution argues that the answer may be both — many fears are indeed overblown, and yet AI may alter the media landscape in unprecedented ways that could result in real harms.

Brookings analysts Zeve Sanderson, Solomon Messing, and Joshua A. Tucker review the academic literature to explain why online misinformation has been less impactful than the coverage it receives in the media would suggest. For instance, the think tank reports research that false news actually constitutes a minority of the average person’s information diet. One recent study quoted estimated that for the average adult American Facebook user, less than 7% of the content that they saw was related to news even in the months leading up to the 2020 US elections.

They also argue that American voters have generally made up their minds long before election day “it is not a stretch to say that 90% of Americans probably already know the party of the candidate for whom they will vote for President in 2024 without evening knowing who that candidate is — and seeing misinformation likely won’t change most people’s vote choices or beliefs.”

The analysts also state that generative AI will change the production and diffusion of misinformation, potentially in profound ways.

“Given this context, we attempt to move away from general fears about a new technology and focus our collective attention on what precisely could be different about AI — as well as what lawmakers could do about it.”

So, what can be done about it?

The Brookings Institution calls for more research, and quickly. “The risk of either over- or underestimating the impact of AI is greatest without rigorous research, as conventional wisdom will define how we talk about and perceive the threat of AI. It’s not too late to prioritize that research by, for example, earmarking more National Science Foundation grants focused on AI.”

One question research might help answer is whether AI-generated misinformation is more persuasive when it’s highly personalized or presented in the form of video evidence. And will TikTok serve GenAI content to users across the demographic spectrum?

“Without rigorous research, we risk making the same mistakes we made previously with social media,” they argue.

READ MORE: Misunderstood mechanics: How AI, TikTok, and the liar’s dividend might affect the 2024 elections (Brookings)

The problem is exacerbated by the lack of resources being used by major social media platforms to address misinformation. Pretty much everyone agrees with this, outside of Meta, YouTube and X, which claim they are doing everything they can to weed out deepfakes (although not to keep extremist views or conspiracy theories off their platforms).

Some are offering new features, like private one-way broadcasts, that are especially difficult to monitor. Politicians are planning livestreamed events on Twitch, which is also hosting a debate between AI -generated versions of President Biden and former President Trump.

The companies are starting the year with “little bandwidth, very little accountability in writing and billions of people around the world turning to these platforms for information” — not ideal for safeguarding democracy, Nora Benavidez, senior counsel at advocacy organization Free Press, told the NYT.

There’s also the inability of technology and legislation to keep pace with developments in AI. “There is a constant adversarial dynamic where the tech gets better before the detection tech,” Renee DiResta, a Stanford research manager told the Financial Times. “It’s the ‘red queen problem’ — we run as fast as we can to stay in the same place.”

Beyond detection, many platforms have been exploring using watermarking or other indicators to assign a signature of authenticity to content before it is published. Both Google and Meta have been introducing invisible watermarking for content generated by their own AI tools.

But sceptics note that this is a work in progress, and only an effective solution if widely and consistently adapted. Meta’s global affairs head Nick Clegg has spoken publicly about the need for common industry standards, while TikTok said it was assessing options for a content provenance coalition.

The Financial Times reports a faint glimmer of hope: that the authenticity crisis will eventually come full circle, with voters returning back to legacy institutions over social media platforms for their information.

Bret Schafer, of Alliance for Securing Democracy, told the Financial Times, “If I’m an optimist here, in five years my hope would be that this actually draws people back to trusting, credible, authoritative media.”