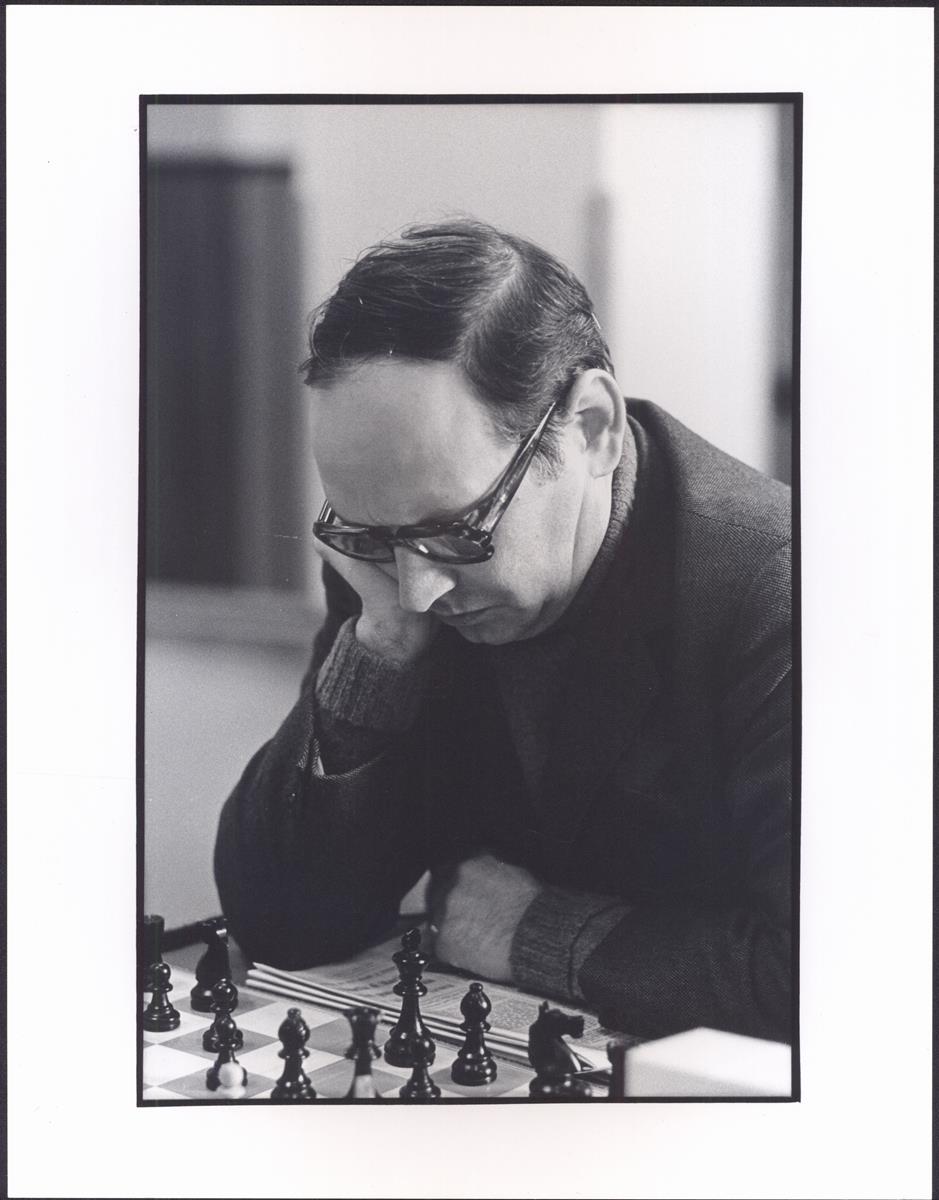

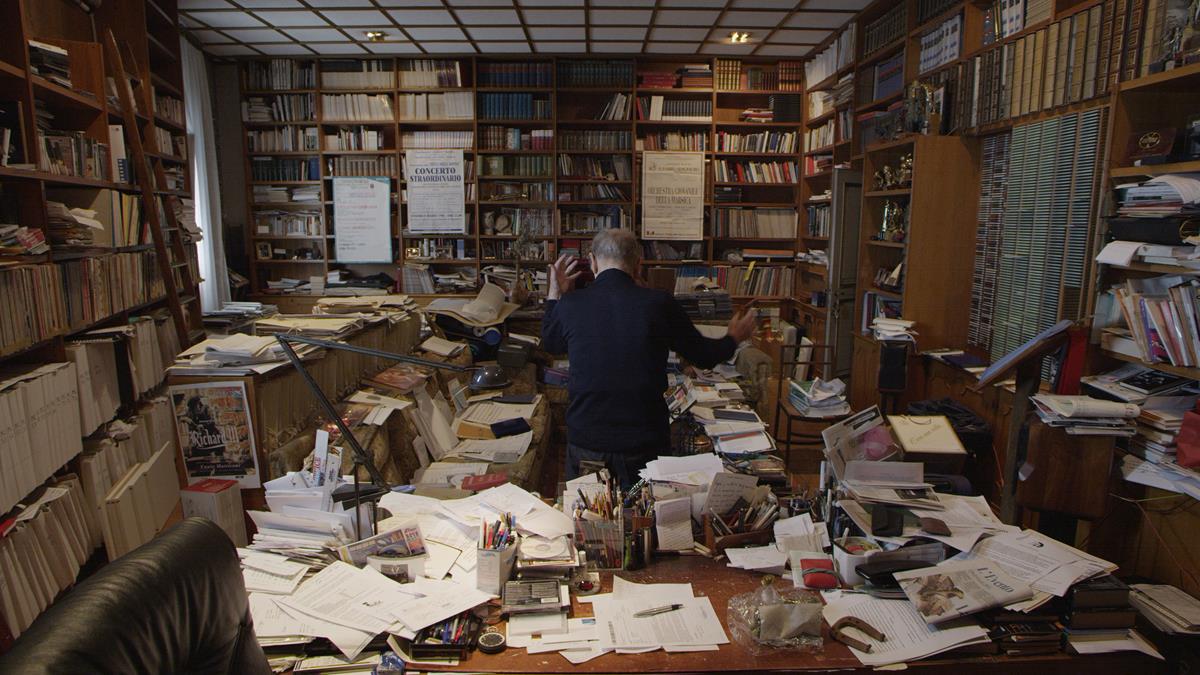

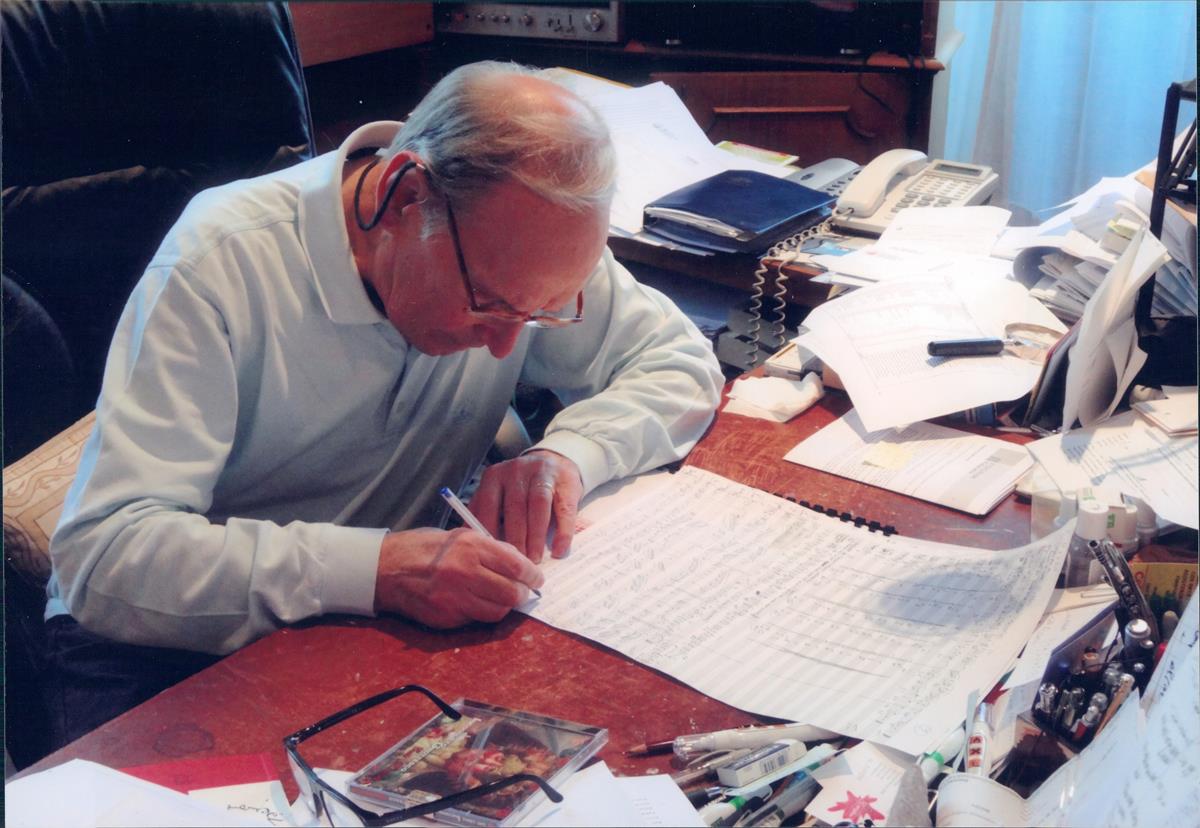

A documentary about the great film composer Ennio Morricone might logically start with the signature tune from one of his classic westerns. Instead, Ennio begins very quietly with just the ticking of a metronome and footage of the man himself working studiously — and working out — in his paper-strewn flat.

“Watching Ennio working is like watching an athlete,” comments director Roland Joffe in the film, which premiered at the 2021 Venice International Film Festival and is being released to cinemas.

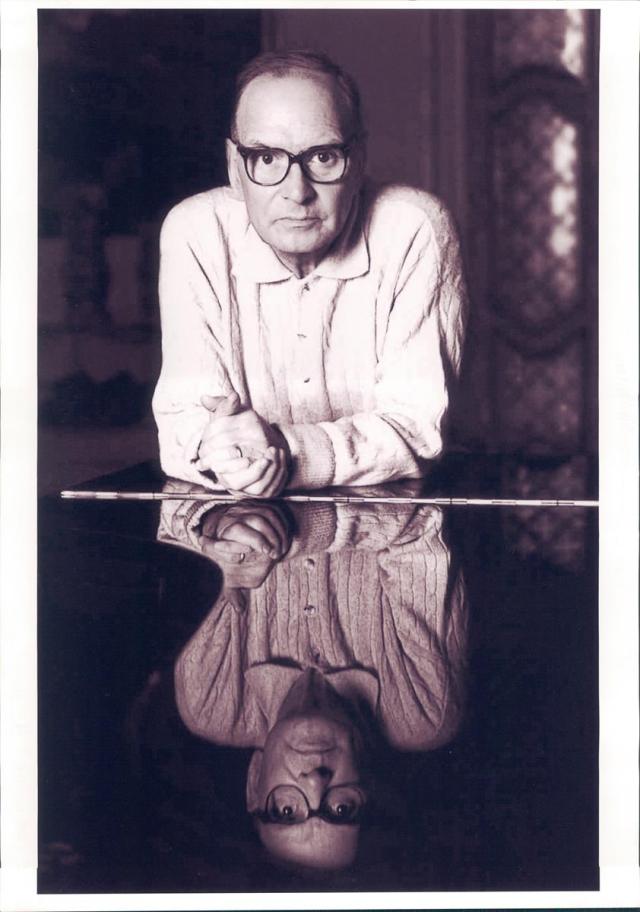

Morricone, who is interviewed for this film before his death aged 92 in 2020, comes across as a quiet, humble, intelligent man who took composition very seriously but not without humor. He also elevated music composition for film to an artform.

The Italian is one of the most influential composers in the history of cinema, with a filmography that includes more than 70 award-winning films. This documentary, produced by Dogwoof and directed by Giussepe Tornatore (with whom he worked on several films including Cinema Paradiso), features snippets of testimony from Wong Kar Wai, Bernardo Bertolucci, Quentin Tarantino, Clint Eastwood, John Williams, Hans Zimmer and Bruce Springsteen.

“This was the most creative music I had heard in a theatre,” says Springsteen on watching The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, “and the only one I rushed out of the cinema to buy the music for.”

These interviews were filmed over five years and are intercut with fragments of Morricone’s private life, recordings from his acclaimed world concert tours and copious clips of classic films as you’d expect, but it is Morricone’s own observations which provide most enlightening.

“In the movies mixing sound without a balance (without silence) can damage the movie and the music,” Morricone says. “Music is an abstract element added to the film and it’s not necessary — but when we need to hear it, we need to let it be free.”

His formative years as a jazz trumpeter and avant garde musician, notably with “Il Gruppo” (with whom he performed for 20 years), play heavily into his inventive sound for cinema.

Gunfight At Red Sands and Bullets Don’t Argue — both from 1963 — were his first westerns, for which he is credited under the pseudonym Dan Savio because of the opprobrium he felt he would receive from fellow composers.

NOT WHODUNNIT, BUT HOW-DUNNIT — DIGGING INTO DOCUMENTARIES:

Documentary filmmakers are unleashing cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality to bring their projects to life. Gain insights into the making of these groundbreaking projects with these articles extracted from the NAB Amplify archives:

- Crossing the Line: How the “Roadrunner” Documentary Created an Ethics Firestorm

- I’ll Be Your Mirror: Reflection and Refraction in “The Velvet Underground”

- “Navalny:” When Your Documentary Ends Up As a Spy Thriller

- Restored and Reborn: “Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)”

- It WAS a Long and Winding Road: Producing Peter Jackson’s Epic Documentary “The Beatles: Get Back”

Classical composer Goffredo Petrassi, for instance, thought scoring music for film “totally anti-artistic.” Petrassi believed, says one commentator, that “commercial music for the cinema was, for an academic musician, like prostitution.”

Yet director Sergio Leone liked what he heard, in particular the innovative use of guitars to sound like riding horses.

“He came to my house,” Morricone recounts. Under the impression he was meeting Dan Savio, Leone was surprised to find in Morricone an old schoolmate who, as 10-year-olds, had shared the same classes.

“That afternoon he took me to see [Akira Kurasawa’s] Yojimbo and explained to me his next film, A Fistful of Dollars had something in common with it.”

The genesis of this soundtrack came from an arrangement Morricone had made years earlier for the record album Pastures of Plenty by American singer Peter Tevis.

“Leone liked it and said why don’t you find me the backing track,” Morricone, who rewrote it and invented a new melody with a whistle, recalls.

There’s even an interview with musician and frequent collaborator Alessandro Alessandroni, who provided that whistle for the film’s score.

“When I saw the movie I was quite surprised because that music is unique,” says Eastwood. “At that particular time no one had tried something so operatic for a western. His music helped dramatize me — which is hard to do.”

Along with the whistle, the score for A Fistfull of Dollars included an electric guitar, the lashing of a whip, the piffero, an anvil, and a bell. He essentially set out a new language for cinematic composition.

Yet Morricone surprisingly admits that he always disliked this score, perhaps because he felt it was a straitjacket to his creativity.

“I always encouraged Sergio to forget it in later films but he insisted ‘give me some trumpet, do the whistle,’” he says.

Indeed, Oliver Stone appears saying that he wanted the composer to work on one of his films and that he instructed Morricone to reproduce the quirky sounds that appear in the Dollars trilogy, likening them to the cartoon sounds of Tom and Jerry.

Morricone was so offended he refused.

For the Italian it was his way or the highway. He was on the point of walking out on movies on several occasions where the director wanted to use pre-recorded music and not rely exclusively on Morricone’s original composition. For Morricone this was more than a point of pride; having a blank slate was the only way he felt free to create.

In editing For A Few Dollars More, for instance, Leone had used the trumpet theme (called Deguello) from the John Wayne western Rio Bravo as temp music. It fitted the scene perfectly and Leone wanted to keep it. Morricone objected

“You want to use an existing piece in the main scene, and I just do the background music? I said, ‘I quit.’”

Rather than give up Morricone, Leone gave up the Deguello, but asked the maestro to write him something similar.

“I thought of a song I’d written years earlier for a TV show sung by one of the Peters Sisters, a contralto with a deep extraordinary voice.”

Morricone rewrote it for trumpeter Michel Lacerenza, incorporating the tonal flutters to mimic the Deguello. Also in For A Few Dollars More, Morricone quotes the opening of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor (later deployed by Andrew Lloyd Webber in Phantom of the Opera) to give a pivotal gunfight an operatic grandeur.

During this time, “Sergio realized how important Ennio was to the soundtrack and that Ennio was beginning to find his own audience,” says Bruno Battisti D’Amario, the guitarist who played on The Good, The Bad and the Ugly.

Raffaella Leone, Sergio’s daughter and a producer in her own right, says there was a complicity between the two “also a lot of discussions — let’s say violent ones. I think that my father depended on Ennio’s music and wanted his movies to depend on music. The music was much more than a soundtrack it essentially was the dialogue of the movie.”

The character played by Charles Bronson in Once Upon a Time in the West is a case in point. He plays the harmonica more than he speaks.

“It is a voice,” says Raffaella Leone. “Entrusting so much of that character to someone else meant putting yourself in their hands. Leone never worked with anyone else.”

Morricone’s music became so integral to Leone that he even had the theme playing on set while they shot Once Upon A Time in America with Robert DeNiro. Morricone had written the score months, even years, before the film was made.

“On this film, the collaboration with Sergio began when he described the movie to me,” he says. “He described it to me in great detail even explaining the framing.”

Synonymous with Leone as he is, the composer worked with a multitude of directors and in all sorts of genres. One of his most celebrated was for period epic The Mission (1986), directed by Joffe, for which Morricone combined an oboe theme with ethnic instruments and a motet — an ancient Catholic musical form.

“There was nothing I was more sure of than that he would win the Oscar,” says the film’s producer, David Puttnam.

Instead, the award went to Herbie Hancock for his arrangement on Round Midnight, a controversial choice given that most of the music used in the film pre-existed.

The snub rankled Morricone. “Herbie Hancock is a good musician, a good pianist and a good trumpeter but half of the film’s music was repertoire and should not have been in the original music category.”

About The Hateful Eight, Morricone says, “I felt like I was avenging myself on the western movie.” That’s because Tarantino wanted Morricone to emulate his work for Leone, but the composer had no interest in repeating himself so he wrote a symphony.

Ironically, it was the only one of six nominations for which Morricone won the Oscar.

Tarantino himself calls Ennio his favorite composer. “I don’t mean movie composer — that’s ghetto. I’m talking about Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert.”

LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION! SPOTLIGHT ON FILM PRODUCTION:

From the latest advances in virtual production to shooting the perfect oner, filmmakers are continuing to push creative boundaries. Packed with insights from top talents, go behind the scenes of feature film production with these hand-curated articles from the NAB Amplify archives:

- Savage Beauty: Jane Campion Understands “The Power of the Dog”

- Dashboard Confessional: Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s “Drive My Car”

- “Parallel Mothers:” How Pedro Almodóvar Heralds the New Spanish Family

- “The Souvenir Part II:” Portrait of the Artist As a Young Woman

- Life Is a Mess But That’s the Point: Making “The Worst Person in the World”

That may be hyperbolic, but his legacy is huge and grown in stature in recent years. Tarantino says he grew up listening to “Ecstasy of Gold,” the electrifying soundtrack to Eli Wallach running around the graveyard in “Ugly,” and used by Metallica to warm up the crowd every time they go on stage.

“I love the sounds, the layering in his music,” says the band’s frontman, James Hetfield. “He has made a lot of people sing his song and it gets my heart going.”

The only regret from Morricone in such a storied career is that when Stanley Kubrick asked him to do A Clockwork Orange it was Sergio Leone who turned it down. He wanted Morricone to himself.