TL;DR

- After a decade of streaming, TV delivered online looks remarkably like cable, writes New York Times TV critic James Poniewozik.

- Enticing viewers to binge watch or dropping episodes weekly enables creators to extend story arcs and go deeper into character, but sometimes the dramatic tension gets lost in the process.

- Interactive experiments like Netflix’s “Kaleidoscope” are dismissed as not being the revolution streaming once promised.

READ MORE: Streaming Changed TV. Is TV Changing Streaming Back? (The New York Times)

The biggest impact that streaming TC has had on the business and aesthetics of television could be its ability to tell stories over longer arcs — but that’s not always a good thing.

Assessing a decade of streaming, The New York Times TV critic James Poniewozik says binging has transformed storytelling and viewing habits but we may be starting to hit that transformation’s limits.

“Giving viewers the option to binge when they please has encouraged a form of storytelling more focused on the season and less on the episode,” Poniewozik writes, adding, “I think something more nuanced is going on: Decision by decision, TV is collectively feeling its way toward figuring out which viewing experience works best for which kind of series.”

He cites two examples: Game of Thrones, though its episodes only occasionally focused on single stories, “might not have become as big a phenomenon without the weekly hype cycle.”

On the other hand, FX on Hulu’s The Bear, whose entire season dropped at once last summer, prompted more buzz and discourse than many of FX’s weekly series. “It may be that this kind of dramedy — character-based, relatively short, not driven by big plot detonations — is better taken in one gulp,” Poniewozik suggests.

READ IT ON AMPLIFY: What Streaming Audiences View and Value (and What They Don’t)

Either way, though, streaming TV is remarkably the same as cable shows of old since in almost every case “you progress, scene by scene, episode by episode, through a narrative order chosen by a creator, not by you or by the roll of some automated dungeon master’s eight-sided die.”

Poniewozik is referring to experiments in non-linear storytelling, which puts the onus on the viewer to chop and change story order and endings.

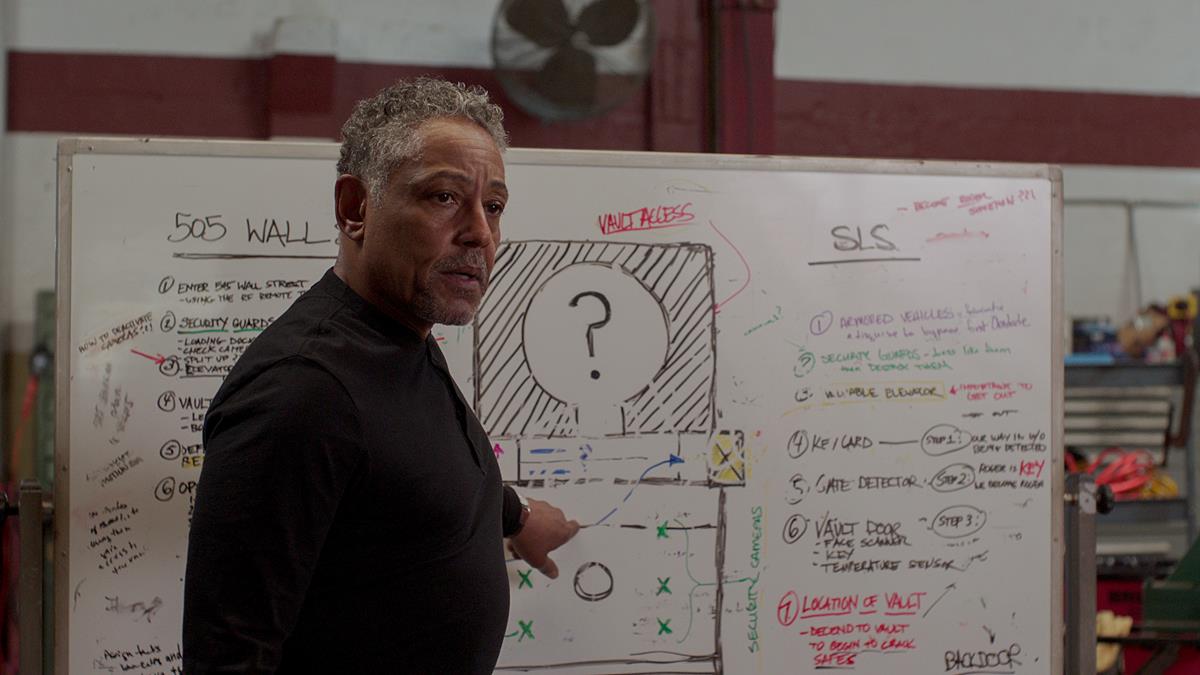

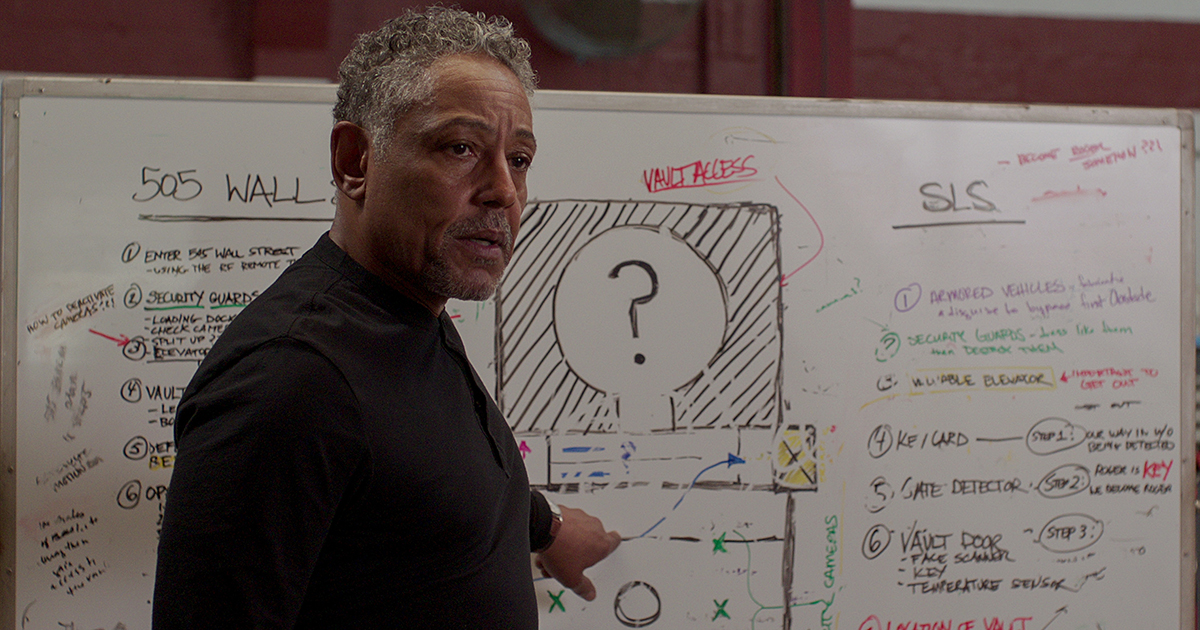

Netflix heist drama Kaleidoscope is the most recent example, but there have been several others. Netflix’s interactive film/show/game Black Mirror: Bandersnatch was perhaps the most successful in allowing viewers to choose the path the story followed. So did the Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt special Kimmy vs. the Reverend; the animated Cat Burglar added a trivia-game element. Netflix was not alone in this either, with Steven Soderbergh going the choose-your-own-adventure route in the HBO series/app Mosaic.

The critic dismisses Kaleidoscope with a shrug, calling it “not especially noteworthy, except for one gimmick,” and more broadly says attempts at interactivity “have gotten no more traction than Smell-o-Vision, maybe in part because our culture already has a popular and relatively young form of interactive amusement, the video game.”

Instead, TV’s dominant format continues to be the static season, in which episodes are served up in a set progression. Often — even on streaming — they arrive once a week.

“The only choosing viewers do is what to watch, when to watch and whether to fill their couch-side snack bowl with chips or pretzels.”

The downside to this is the flabby nature of some shows which are padded out to retain viewers over more hours (or weeks if being gradually released) than is necessary for the story.

READ IT ON AMPLIFY: Platforms Are Using Audiences as a New Means of Distribution (and Here’s Why That’s a Problem)

I’m a fan of William Gibson’s The Peripheral adaptation made for Amazon Prime but this show could have benefitted from a tighter runtime over fewer episodes. Arguably, Andor, the Star Wars prequel series for Disney+, got its quotient of run time to emotion right. Importantly, its episodes ranged around the 40-minute mark. In an interview with Rolling Stone, showrunner Tony Gilroy, dismissed “the idea that you have to wrap up every episode in a bow” and defended the series’ slow-burn start as a necessary “investment.”

The three-season arc of His Dark Materials produced by Bad Wolf for the BBC is a superb example of treating the source material and the audience with respect, devoid of unnecessary padding, when in other hands you can imagine the storylines being strung out and the drama dissipating.

As Poniewozik concludes, streaming has “added to TV’s bag of tricks, giving creators the option of making more unitary long-form works.” Other times it imposes the expectation of length where it isn’t needed.