Shigeko Kubota: Liquid Reality — on display now at MoMA — is a retrospective for Japanese American video sculptor and diarist Shigeko Kubota. The installation is also the first time in a quarter-century that her work has been shown as a solo exhibit .

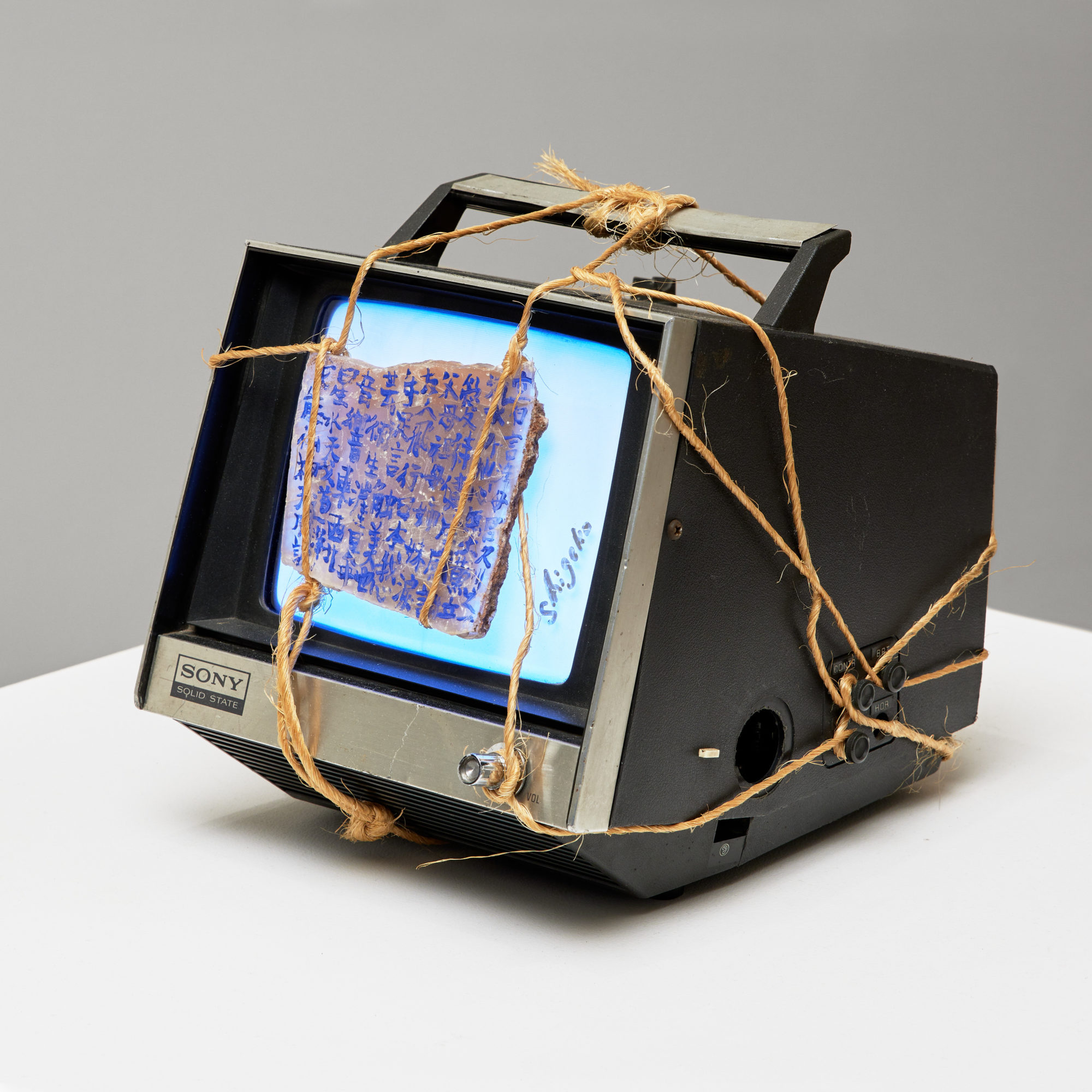

According to MoMA Magazine‘s Erica Papernik-Shimizu and Veronika Molnar, Kubota’s video sculptures “were among the first artworks to combine video technology with elements of the natural world, let alone sculptural form.”

Kubota’s later video diaries, as she called them, also illustrated a concept creators still grapple with in the era of social media: “[S]he was very much considering her own position in relation to her subjects, and exploring video’s paradoxical quality as both a distancing device and tool for self-examination.”

READ MORE: Everything Is Video (MoMA Magazine)

OK… But What Qualifies as Video Art?

In order to understand Kubota’s place in the modern art canon, it’s important to contextualize the medium and the artistic movement during which she created.

For a concise take on the subject, look no further than this video from The Art Assignment. Host and curator Sarah Urist Green makes a persuasive 10-minute “Case for Video Art” in which they remind 21st Century viewers that early cinema was naturally experimental, since the technology and the rules for creators were coevolving, making and breaking unwritten rules and attracting both artists and futurists.

Video art and film were both democratized with the advent of the Sony Portapak (In fact, Hermine Freed wrote, “The Portapak would seem to have been invented specifically for use by artists.”) and a cultural obsession with television. Uncoincidentally, art from the 1960s and ’70s was frequently multimedia, combining painting, sculpture, music, dance, and, yes, moving images.

However, in the Internet Age, “the line between video art and not video art is blurrier than ever,” Urist Green acknowledges.

Watch the video below to learn more.

More About Shigeko Kubota

The New York Times, in her obituary, noted Kubota as “one of the first artists to see the artistic potential of video technology, which she integrated in intensely personal sculptural works.”

The article also highlighted her connection to the Fluxus movement and contemporaries like Yoko Ono and Nam June Paik (her husband and fellow video artist, whom the article name drops before citing Kubota’s own bona fides, tsk tsk).

READ MORE: Shigeko Kubota, a Creator of Video Sculptures, Dies at 77 (New York Times)

For a more feminist review of Kubota, turn to Jonathan Keats’ take for Forbes. Writing about and placing the current MoMA exhibition, Keats acknowledges her relationship to Paik as both a partner and a fellow maker: “Kubota was married to another new media visionary, the Korean-American artist Nam June Paik, who is venerated today as the ‘father of video art.’ But Paik’s approach to the medium was too conservative by Kubota’s reckoning.”

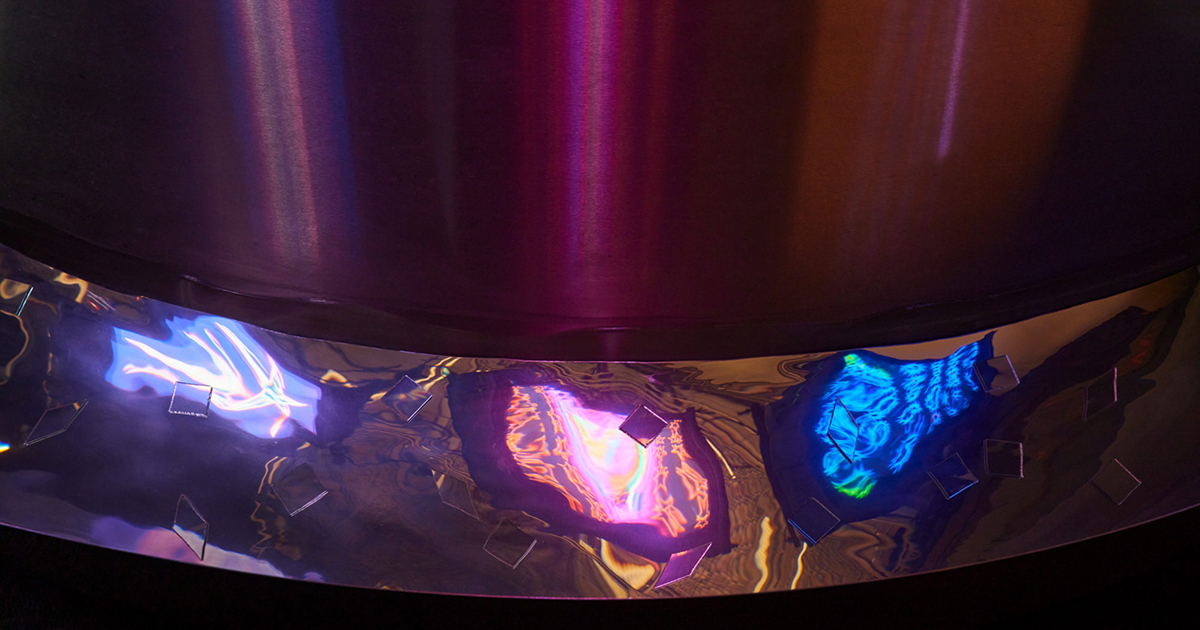

Rather than continue to needle her partner, she took matters into her own capable hands, experimenting with materials so that she became known for “creating a hybrid space where distinctions between image and reality lost meaning, pooling in pure experience,” according to Keats.

Now, more than five years after her death, Keats says, “Like an echo, or the roar of an ocean, Kubota’s video is everywhere and nowhere. Perhaps this can be seen as a premonition of our own age, in which people are tethered to the mobile technologies that are supposed to set them free. More optimistically, her work can be viewed as an escape we might yet make by privileging experiences over the mechanisms that deliver them.”