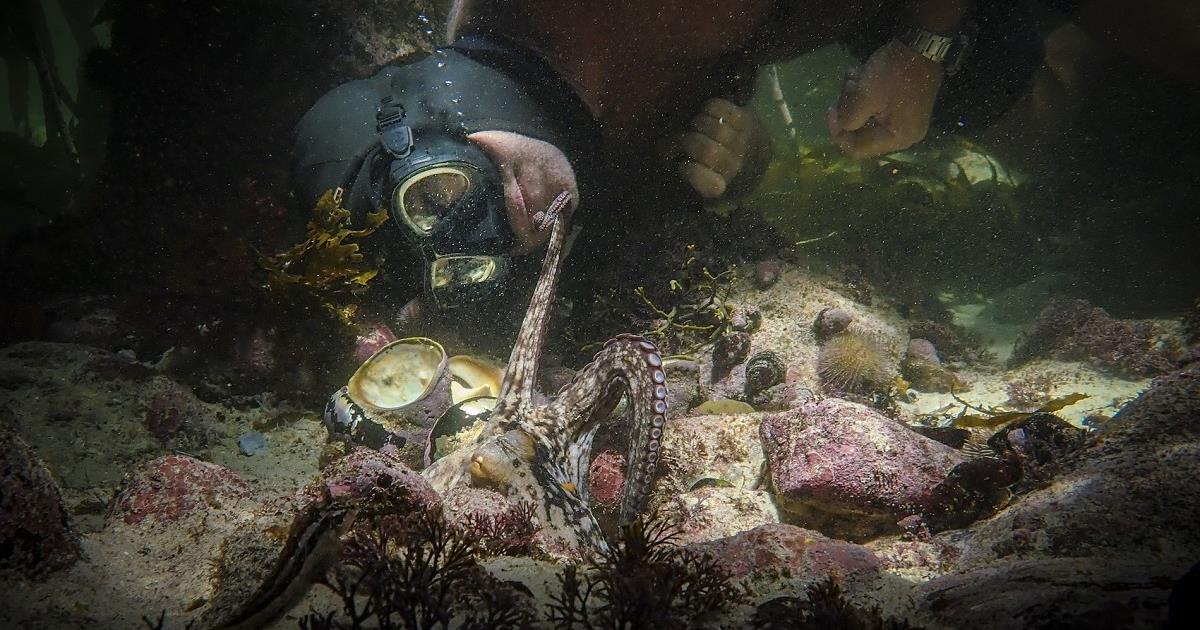

Now streaming on Netflix, Life in Color with David Attenborough is the latest nature series to be hosted by the renowned British naturalist. The three-part docuseries, which was produced by Humble Bee Films and Australian-based SeaLight Pictures, travels from the rainforests of Costa Rica to the snowclad Scottish Highlands to reveal how animals use color to survive and thrive in the wild.

“Animals of all kinds use color in a multitude of different ways,” says Attenborough. “New discoveries are giving us fresh insights into the lives of these animals and new cameras are allowing us to see into a world of color as never before. We’re only just beginning to understand the many ways in which animals use color, particularly those colors we can’t even see. For us color in the natural world is a source of beauty, of wonder, but for animals, it’s a tool for survival.”

“Attenborough’s Netflix documentary series Life in Color with David Attenborough is a stunning look at the animal kingdom, and how colors impact the natural world,” Brooke Mondor writes in Looper:

“In each episode, Attenborough shows a wide variety of colorful creatures and takes a deep dive at a specific way they use color: whether to stand out to find a mate, hide from a predator, or disguise themselves, so they can catch a meal. The scientific information is paired with beautiful cinematography, showing both extreme close-ups and aerial shots of stunning landscapes. And of course, much of the focus is on color, with dazzling shots of vivid hues.”

READ MORE: The Nature Doc That Everyone’s Binging On Netflix (Looper)

Innovative camera technologies — some developed especially for this series — allow viewers, for the first time, to see the world as animals do, revealing colors and patterns that are usually invisible to human eyes. Humble Bee Films and SeaLight Pictures teamed up with Prof. Viktor Gruev from Illinois University in the US and Prof. Justin Marshall from the University of Queensland in Australia to develop the specialist camera technology for the series. A UV beam-splitter camera system allowed the series to film colors in the ultraviolet range, while a new camera able to visualize polarized light allowed the filmmakers to detect otherwise invisible patterns on some animals.

Series producer Sharmila Choudhury detailed the two specialist camera systems in an interview with Margeaux Sippell for Movie Maker magazine. UV cameras, she acknowledged, have been around for a while, but haven’t really been used for broadcast filmmaking. “They’re mainly used for science,” Choudhury said:

“Ultraviolet cameras can’t film both in our human color vision and ultraviolet at the same time, so we had to adapt the system to have these two cameras — a beam splitter system, it’s called — where the light is split into two parts that the ultraviolet goes into one camera, and the other color range, red, green, blue — we call it RGB — goes into the other camera.”

The polarization cameras are so new, however, that before now they had only been used by scientists. These cameras were employed for a segment from the episode on fiddler crabs in the mudflats of Northern Australia, where the crabs use polarized light to spot other crabs from a distance.

Choudhury said the polarized cameras “had only recently in the last couple of years been developed by scientists in the lab for very different purposes. One was being used in the US for medicine to detect cancerous tumors, and another one was developed in Australia by a biologist who was studying underwater animals. But again, in tanks in his laboratory — so we had to work with the scientists to adapt those two cameras to take out into the field and to test them to film real animals. So that was the challenge.”

READ MORE: For David Attenborough, Life in Color Is a Lifelong Dream Fulfilled (Movie Maker)

Other animals featured in the series include the Mandrill baboons, the Costa’s hummingbirds, the Magnificent bird-of-paradise, the Bengal tiger and the Fiddler crabs. “Costa’s hummingbird is tiny, less than 10 centimeters in size, but it has one of the most extraordinary displays,” says Choudhury, who noted that the hummingbird’s display is over so quickly that it could only be captured with a super high-speed camera and powerful telephoto lenses.

The production team partnered with David Rankin, a researcher from the University of California, who staked out the best territories. Guthrie O’Brien, from the Life in Color team, acted as a spotter, with each bush and tree assigned a code. As the birds flitted back and forth, O’Brien called out the codes, while camera operator Barrie Britton rapidly swiveled the camera around to locate the birds with his lens.

“It took a lot of patience to get close enough to film the alpha male,” Choudhury recounts:

“I had to respect their boundaries, making small steps closer each day to gradually gain their trust. Our patience paid off. Towards the end of the three weeks, I didn’t have to hide as much from him and sensed a kind of mutual respect. Primates always give the impression they are not noticing humans, whilst keeping a close eye and maintaining the distance between them and the camera crew at their will. But when they recognize you and accept you are not there to do harm, if they decide, they will let you do your thing whilst they do their thing.”

“Nature documentaries often reveal beautiful moments our limited vision cannot see, and that’s even more true for Life in Color with David Attenborough,” Marco Vito Oddo writes in Collider ahead of a clip from the series:

“In the clip, the use of an ultraviolet camera shows the hidden scale patterns on fishes that, to us, look practically the same, even though they reveal that the fish are actually from different species. The short clip illustrates perfectly what we can expect from the show, which developed special tools to amaze the audience with the colors that are invisible to human eyes but vital to animal interactions.”

READ MORE: Discover the Secret Language of Fish In This ‘Life in Color with David Attenborough’ Clip (Collider)

Aside from the complex camera technology developed for the series, the production team also needed expert help when it came to setting up shots. Erin Berger, in Outside magazine, details the setup for capturing a ferocious battle sequence between two extremely territorial Strawberry poison dart frogs. “The aim was to demonstrate just how important color was in everything the frogs did, from warning off predators to showing potential mates their fitness,” she writes.

To capture the fight scene, the production team enlisted animal behaviorist Yusan Yang, whose research is featured in the docuseries. “Yang knew that a more toxic frog wouldn’t be shy around camera equipment, and that Panama’s Solarte Island would be an ideal place to shoot because the red-orange frogs there are among the most aggressive. She also knew that the two frogs would need to be the same color if they wanted to capture a battle,” Berger notes. But it was up to the camera crew to locate two male frogs close enough to each other’s territories for a potential clash, as well as setting up the shots and lighting before settling in to wait for an appearance.

“As anyone who read every single article about the Planet Earth II marine iguana scene may know (just me?), it’s not exactly a closely held secret that most nature films take cinematic liberties to tell a story,” Berger writes:

“The Life in Color team had to cross their fingers they’d witness a frog fight, but the rest of the visual storytelling was carefully planned out beforehand. The camera crew captured images like close-ups of the frogs’ pugnacious-looking little faces, and establishing shots of the intruder frog entering the scene, at different times using unobtrusive telephoto lenses. The footage could then be knitted together to create a cohesive story of two confident frogs who meet on a patch of rainforest that’s not big enough for the both of them.”

But the battle royale between the two poison dart frogs “plays out on screen exactly as it happened, enhanced only by slowing down certain clips for dramatic effect,” Berger notes. “In real life, you’d see two penny-sized frogs making jerky hopping motions at each other for a few seconds. The final scene plays out over several minutes, and it’s hard not to anthropomorphize the two angry little guys by the time we have a clear victor.”

“They just yielded themselves beautifully to drama, to humor,” Choudhury tells Berger. “They’re kind of the dream subjects for filming.”

READ MORE: Inside the Most Fascinating Scene from ‘Life in Color’ (Outside)

Like most of the nature specials produced by the BBC, many of which Attenborough hosts, Life In Color is rife with spectacular photography, whether it’s in macro — like an overhead view of flamingoes’ mating ritual — or in micro, like scenes of butterflies mating. The colors presented really pop, and they seem to be a good test of whether your TV is up to snuff or needs some recalibration (it seems that our 13-year-old Vizio is doing just fine in that regard),” Joel Keller writes in Decider:

“Where Life In Color shines to us is the technology used to capture what some species see that we can’t with our naked eyes. He explains some of the technology that is being used, like a two-camera setup with a UV filter that filters out everything but UV to one camera while simultaneously reflecting visible light to the other. But the technology isn’t explained all that much in the first episode, especially the one that shows the polarized view that the fiddler crab sees.

“The third episode, though, should go about explaining how the nature photographers set up these new rigs, and that makes gearheads like us happy.”

READ MORE: Stream It Or Skip It: ‘Life In Color With David Attenborough’ On Netflix, An Exploration Of How Wildlife Communicates Using Colors (Decider)

Want more? Watch the behind-the-scenes video from Mashable below, “How David Attenborough’s ‘Life in Color’ captured what the eye can’t see,” featuring series producer Sharmila Choudhury and executive producer Colette Beaudry: