TL;DR

- Writer Kyle Chayka examines the impact that social media newsfeeds have had on taste. He argues that by favoring engagement and removing human curation, we have created a more homogenous culture, both online and in real life.

- He says that the equation of success with engagement has also acted as a new kind of gatekeeper, since anyone can publish content online, but trends largely dictate whether anyone will have the opportunity to experience it.

- Despite the current ubiquity of algorithmic feeds, Chayka has a few ideas for how we can reclaim or develop our individual sense of taste.

Did the advent of the “curated” social media feed spell the end of good taste — or any taste at all? And is there any art still challenging us to consider what we actually like, as creatives shift from following their muse to gaming the algorithm?

In his new book, “Filterworld,” journalist Kyle Chayka considers the origins and inadvertent consequences of a society that consumes content, rather than appreciates art.

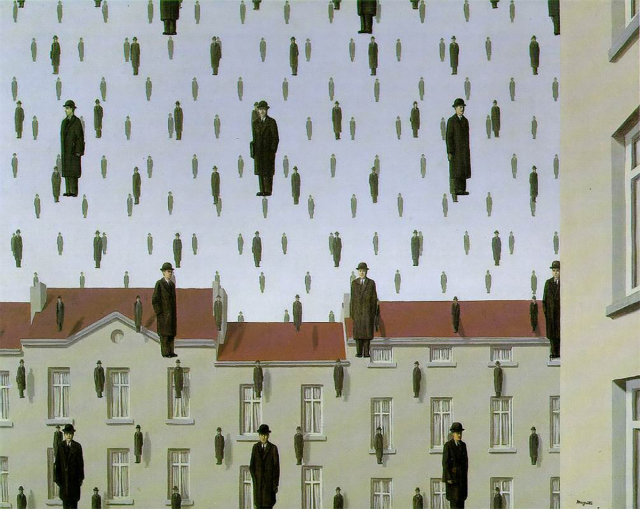

Chayka tells Esquire that the era of passive consumption (perhaps coupled with an aversion to anything that smacks of elitism) “makes the cultural landscape less interesting, but it also takes away this opportunity for us to encounter art that is really shocking or surprising or ambiguous.”

Coffee Shop and Content Conformity

This online phenomenon has had IRL consequences. “[T]he coffee shop aesthetic was kind of the canary in the coal mine. It was the most visible symbol of this homogenization that was happening over the Internet,” Chayka recalls to Lizzie O’Leary, host of Slate’s “What Next: TBD.”

(If you don’t know what he’s talking about, Google “hipster coffee shop in [your city/town].” Chances are good that it features white subway tiles, mid-century modern-esque furniture, and a fiddle leaf fig tree.)

How did this happen? “Instagram and other feeds have really shaped how we see everything in the world. Like, all forms of culture has to, kind of, flow through them,” Chayka says.

READ MORE: Have Algorithms Ruined Our Culture? (Slate)

“Algorithmic feeds and recommendations have kind of guided us into conforming to each other and kind of having this homogenization of culture where we all accept the average of what everyone’s doing,” Chayka explained to Fresh Air’s Tanya Mosley.

These recommendations are acting on “us in two different directions,” he says. “For us consumers, they are making us more passive just by, like, feeding us so much stuff, by constantly recommending things that we are unlikely to click away from, that we’re going to tolerate, not find too surprising or challenging. And then I think those algorithmic feeds are also pressuring the creators of culture, like visual artists or musicians or writers or designers, to kind of shape their work in ways that fits with how these feeds work and fits with how the algorithmic recommendations promote content.”

Although creators now have a way to bypass traditional human gatekeepers (the editors and critics and producers), Chayka says they’ve traded a regime dictated by personal tastes and connections for one ruled by engagement metrics.

“On the internet, anyone can put out their work, and anyone can get heard,” he says. “But that means to succeed, you also have to placate or adapt to these algorithmic ecosystems that I think don’t always let the most interesting work get heard or seen.”

Capitalizing on the Algorithm

While consumers are at the mercy of “the algorithm,” let’s not forget that these feeds are managed by corporations that tweak them to benefit their metrics (and their bottom line).

Chayka cites Netflix’s home page as a prime example of how a company leverages its algorithm to serve you content that they want you to watch.

“There’s this problem called corrupt personalization, which is the appearance of personalization without the reality of it,” Chayka explains. “Netflix is always changing the thumbnails of the shows and movies that you are watching in order to make them seem more appealing to you.”

In fact, in May 2016, Netflix Head of Product Creative Nick Nelson touted this as an example of an improved user experience.

Unfortunately for them, Chayka says, “An academic did a long-term study of this by creating a bunch of new accounts and then kind of giving them their own personalities. …what this academic found was that Netflix would change the thumbnails of the shows to conform to that category that the user watched, even if the show was not of that category. …the algorithm, in that way, is kind of manipulative and using your tastes against you.”

Chayka is worried that this is set to get even worse as gen AI proliferates. “AI is kind of promising to just spit out that average immediately… It’ll take in every song, every image, every photograph and produce whatever you command it to. But that output will just be a complete banal average of what already exists.”

READ MORE: How social media algorithms ‘flatten’ our culture by making decisions for us (NPR)

Is There Any Hope?

Riding the wave of early ‘00s nostalgia is a longing for oddity and sense of serendipity that was a hallmark of the pre-newsfeed Internet. Is there any way to regain it?

“People are starting to get bored of this whole situation,” he tells Mosley. That gives him hope. He predicts: “As users start to realize that they’re not getting the best experience, I think people will start to seek out other modes of consumption and just build better ecosystems for themselves.”

(We built it, so we can break it, I suppose?)

Chayka points to the EU’s regulatory efforts (including the Digital Services Act) as a step in the right direction for breaking the absolute power of the algorithmic newsfeed. Short of that, in the US, we could stand to break up some of the Big Tech monopolies.

“I think increased competition — like if we can break down the monopolies of Meta and Google — would actually lead to a wider diversity of experiences,” Chayka told O’Leary.

In the interim, Chayka suggests to Esquire’s Jon Roth: “One answer to Filterworld, to the dominance of these algorithmic feeds, is to find those human voices. Find tastemakers who you like and really follow them and support them and build a connection with those people.”

You can also choose to completely eschew social media, as Chayka did for a period of time.

However, Chayka found “the Internet was no longer designed to function without algorithmic feeds,” as he writes for the New Yorker. “… Blogs and other Web sites whose function was to aggregate headlines or highlight trends, like the original Gawker, had vanished in favor of a network of feeds. The New York Times app, which in the absence of Twitter became my primary way of checking the news, featured a ‘For You’ tab, much like TikTok’s, that suggested articles based on ones I’d clicked previously. …. But that kind of algorithmically guided consumption was exactly what I was trying to avoid. What I was after, most of all, was a little bit of the feeling I’d had online in the early days of the Internet: a sense of creative possibility and even of self-definition.”

READ MORE: Coming of Age at the Dawn of the Social Internet (New Yorker)

So how do you develop a sense of personal taste? He tells Roth “[t]astemaking is almost just being more conscientious about cultural consumption, being more intentional in the way that we’ve become totally intentional about food, right?”

Chayka wishes that we’d translate our foodie culture to the arts: “I would love it if people took more pride in going to a gallery, going to a library, going to a concert series at a concert hall. I think those are all acts of human tastemaking that can be really positive.”

Addressing the charge of elitism, Chayka says, “It’s just about creating a human connection around a piece of culture that you enjoy, and that should be open to anyone.”