TL;DR

- Tech giants continue to bet on XR devices one day replacing smartphones as the dominant computing platform globally, with billions of daily users.

- That day was supposed to have arrived already, so what happened?

- All consumer tech faces tradeoffs, but XR devices require so many points of optimization, including heat, weight and battery life, that the answer may lie not in new technology but in new science altogether.

READ MORE: Why VR/AR Gets Farther Away as It Comes Into Focus (Matthew Ball)

Efforts to build VR/AR or extended reality wearables have been going on for more than a decade — and we seem as far away as ever.

There have been technical advances, of course, with some use cases, but the day by which we’d all be accessing the internet (or metaverse) for mixed reality or immersive experiences is supposed to have arrived by now.

Matthew Ball, a tech investor and widely read commentator on the metaverse, is as nonplussed as the rest of the industry as to when it will happen.

“As we observe the state of XR in 2023, it’s fair to say the technology has proved harder than many of the best-informed and most financially endowed companies expected,” he writes in an exhausting 11,000 word blog post, which we’ve summarized.

“In 2023, it’s difficult to say that a critical mass of consumers or businesses believe there’s a ‘killer’ AR/VR/MR experience in market today; just familiar promises of the killer use cases that might be a few years away.”

Magic Leap was founded in 2010, the same year Microsoft started development on its HoloLens platform. The first Google Glass prototype was in 2011, Oculus was founded in 2012, with Facebook acquiring the company in 2014, and Amazon began development of its Alexa-based AR glasses sometime in 2016 or 2017. Recent reporting says Apple’s AR glasses, which were once targeted for a 2023 debut and then pushed to 2025, have been delayed indefinitely.

Despite the best efforts of the world’s leading tech and computing giants, no one has found the right formula.

“Many entrepreneurs, developers, executives, and technologists still believe in AR glasses that will eventually replace most of our personal computers and TV screens. And history does show that over time, these devices get closer to our face, while also more natural and immersive in interface, leading to increased usage too. But why is this future so far behind?” Ball asks.

As he points out, in 2015 and 2016, Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg repeated his belief that within a decade, “normal-looking” AR glasses might be a part of daily life, replacing the need to bring out a smartphone to take a call, share a photo, or browse the web, while a big-screen TV would be transformed into a $1 AR app.

“Now it looks like Facebook won’t launch a dedicated AR headset by 2025 — let alone an edition that hundreds of millions might want,” Ball writes.

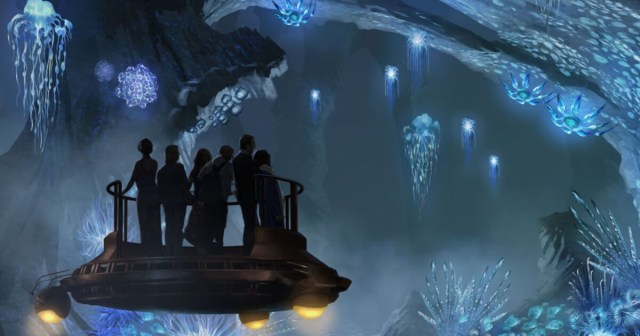

There is some growing deployment. For example, XR is selectively used in civil engineering and industrial design, in film production, and on assembly lines and factory floors. Some schools use VR some of the time in some classes (perhaps for virtual frogs to dissect). VR is also increasingly popular for workplace safety training; Johns Hopkins has been using XR devices for live patient surgery for more than a year.

The delay in XR progress is not for lack of investment. Meta alone has been spending $10-12 billion per year on its XR initiatives. Ball estimates that Meta has spent $50 billion to date, against $6 billion in revenue, but it’s not alone. Microsoft, Apple and others have spent millions if not billions on tech that hasn’t succeeded to break into the mainstream.

Perhaps that’s because, as Epic Games CEO Tim Sweeney intimated to Venture Beat last December, we need not just new technology but, to some extent, new science in order to build an AR platform that’s a substitute for smartphones.

“Many people I know believe that absent extraordinary advances in battery technology and wireless power and optics and computer processing, we simply cannot achieve the XR devices that would conceivably replace the smartphone — or merely engage a few hundred million people on a daily basis,” says Ball.

XR device batteries must be small and lightweight while also being powerful and efficient. The display (which produces still more heat, only this time an inch from the user’s face) adds still more weight. The minimum spec is typically defined as 8K pixels, although many believe 16K to be optimal. This means several times as many pixels as the average TV, which yet again translates into more cost, weight and battery drain.

Yet the number of pixels is only half of the equation. The other half is how frequently they are updated. Most video games target a 60 Hz refresh rate. Some titles will support 120 Hz or more. Since it needs to be operated outdoors, screen brightness needs to be exceptional (again generating heat). Devices need to be equipped with sensors and cameras and be able to do things that other devices cannot.

“All consumer tech faces tradeoffs and hard problems. But XR devices require so many points of optimization — heat, weight, battery life, resolution, frame rate, cameras, sensors, cost, size, and so on. If Zuckerberg can crack this, the financial returns may be extraordinary.”

Zuckerberg knows the challenge. In early 2021, he said, “The hardest technology challenge of our time may be fitting a supercomputer into the frame of normal-looking glasses. But it’s the key to bringing our physical and digital worlds together.”

The smart money — some would say the optimistic money — is on Apple. It is reportedly set to unveil a mixed-reality device soon and stands alone in its ability to “produce world-class hardware” that “works in harmony with a bespoke operating system and interface.”

Yet reports suggest the device will be at least $2,000, and more likely $3,000, “which will limit its appeal and suggests that it is primarily for those who use software to design 3D objects,” such as animators or architects — at least in the short-to-medium term.

Ball maintains that for VR to take off we need a device with an 8K display running at 120 Hz, “thereby avoiding nausea for a substantial portion of users,” that includes a dozen cameras, weighs less than 500 grams, and costs less than $1000, or perhaps even less than $500.

But then the application needs to be compelling, too.

Watching VR movies, VR sports, virtual meetings or classrooms or playing VR games. Lots of ideas have been tried but none has so far resonated with millions of users, let alone hundreds of millions.

“Without compelling experiences, users won’t buy VR devices at scale, and but without a large and active install base, developers won’t focus on these platforms. And to this end, many developers focus on 3D applications, but few on VR.”

To drive adoption, “VR games need to be better than the alternatives, such as TV, reading, board games, Dungeons & Dragons, video games, and whatever else,” he says. “But for the most part, VR loses the leisure war. Yes, it offers greater immersion, more intuitive inputs, and more precise (or at least complex) controls. But the downsides are many.”

The onramp to XR (AR/VR/MR, etc.) will be to incorporate it alongside existing devices and behaviors rather than displace them. Ball uses the example of GPS. We drive a car with GPS; we don’t drive GPS instead of a car, and GPS doesn’t replace the onboard computer either. What’s more, many of us travel more often because GPS exists.

“To exist, XR devices need not upend convention, just deliver better and/or faster and/or cheaper and/or more reliable outcomes. But even under these more moderated measures, the future seems far off.

“GPS began to see non-military adoption in the 1990s, but it took another two decades to mature in cost and quality to become a part of daily life.”