“The scene wasn’t working. It was a moment from the Pixar film Coco, still in production at the time — the part when the family of Miguel, the main character, finds out he’s been hiding a guitar. It takes place at twilight or just after, a pink-and-purple-tinged time of day everywhere, but even more so in fictional Pixarian Mexico. And Danielle Feinberg, the photography director in charge of lighting the movie, didn’t like it. She pressed Pause with a frown.”

Source: Adam Rogers, Wired

AT A GLANCE:

Over at Wired, Adam Rogers walks us through the complex process for lighting computer animated films in an excerpt from his forthcoming book, “Full Spectrum: How the Science of Color Made Us Modern,” available May 18 from HMH Books & Media.

“Lighting a computer-rendered Pixar movie isn’t like lighting a film with real actors and real sets,” Rogers observes. “The software Pixar uses creates virtual sets and virtual illumination, just 1s and 0s, constrained only by the physics they’re programmed with.”

Lights, pixels, action, indeed. “Real-world cameras and lenses have chromatic aberration,” Rogers continues, “sensitivities or insensitivities to specific wavelengths of light, and ultimately limits to the colors they can sense and convey — their gamut. But at Pixar the virtual cameras can see an infinitude of light and color. The only real limit is the screen that will display the final product. And it probably won’t surprise you to hear that the Pixarians are pushing those limits too.”

Returning to the example of Pixar’s Coco, Rogers describes how a research trip to Mexico influenced the final look of the film. Recalling the greenish tint of fluorescent-lit interiors the filmmakers had seen while on the trip, Feinberg opted to use that same effect for the pivotal scene inside Miguel’s home. The choice was an unusual one because the conventional language of cinema usually classifies greenish light as “spooky,” Rogers notes. It was a risk, but director Lee Unkrich agreed with the decision, and “the green glow, which usually had one narrative meaning, assumed another.”

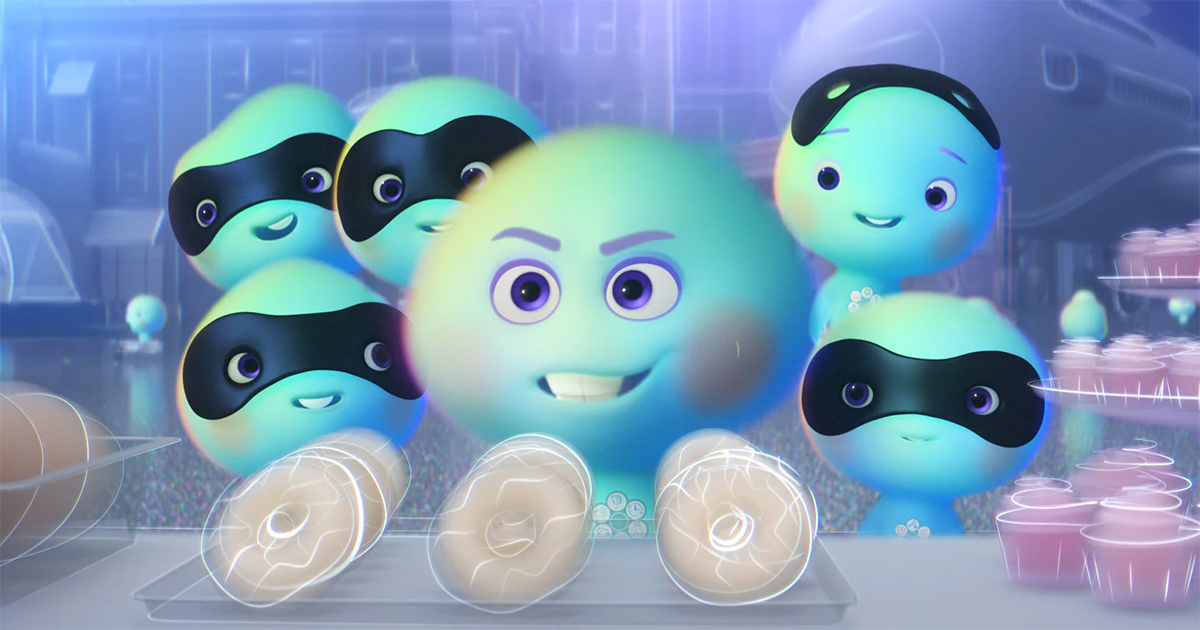

From the near absence of green in the first act of WALL-E and the luminous orange marigolds that populate Miguel’s trip to the Land of the Dead in Coco, to the cool blue luminosity of the afterlife and the warm sepia tones of New York City in Soul, Pixar develops a story-specific color script for each of its films. But Coco’s Land of the Dead sequences, which use every color on the spectrum and take place at night and in the absence of weather, presented major challenges to the filmmakers. “Those are three pretty typical things we use to support the story,” Feinberg said. The solution was to vary the amount of luminance, or light, to elicit emotion. “Control the lighting, control the colors, control the feelings. That’s filmmaking,” Rogers writes.

Always working with an eye towards the future, Pixar is also pushing the limits of color as it can be perceived by the human eye. Rogers describes the studio’s special screening room boasting a custom-built Dolby Cinema projector head with six beams of light coming from a single source and a dynamic range more than 10 times brighter than a “civilian-class” Dolby Cinema. “We’ve goosed this projector with an extra 600 percent laser power. We can get well above a thousand nits on this screen. It’s one of the most linear, perfect reference color-grading displays you can conceive of,” said Pixar senior scientist Dominic Glynn.

“This projection room is where wide-color-gamut, high-dynamic-range colorcasting abilities merge with Pixar’s creation of virtual sets, each with their own virtual physics of light,” Rogers writes. “People like Glynn can actually generate a world of color wholly unlike the one you and I usually live in.”

Want more? Head over to Wired to read the full story: How Pixar Uses Hyper-Colors to Hack Your Brain.