TL;DR

- Wim Wenders talks about his film “Perfect Days,” which began life as a commission for a promotional documentary about Tokyo’s unique public toilets.

- Wenders strove to make a verité drama that is neither quite documentary nor quite fiction but hopefully offers a truthful encapsulation of its subject.

- One metaphor Wenders uses is the Japanese concept of “komorebi,” which conveys the idea of shadow and light and by extension an act of ritual for the film’s janitor character.

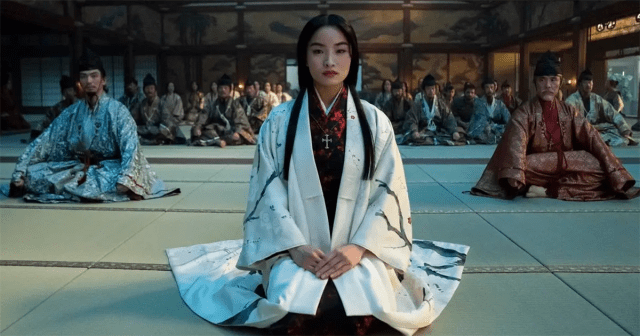

The slow, meticulous and mundane routine of a toilet cleaner in Tokyo is the subject of German auteur Wim Wenders’ latest film and it has critics waxing lyrical about its transcendental and poetical exploration of life.

Perfect Days was nominated for an Oscar for best international feature, and won Japanese screen icon Kôji Yakusho the Best Actor award at Cannes 2023 for his turn as the lead character Hirayama.

“I see out of the corner of my eyes,” the director told A.frame. “Films very often tell what’s in the center of your vision, and Hirayama, is a person who sees a lot more and pays attention to some of the little things we forget to. He sees the homeless man who lives next to one of these toilets; he respects, greets, and treats him like everybody else. Hirayama is a person who sees everything that gets lost so often in movies.”

Ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, The Tokyo Toilet Project invited contemporary designers and architects to create 17 public bathrooms in Japan’s capital. Wenders was initially invited to make a series of promotional documentary shorts about the unique facilities, but on seeing them himself he came up with an idea for a fiction feature.

With co-writer Takuma Takasaki, Wenders wrote a script in three weeks. The verité drama was shot in Tokyo over 16 days, with Wenders embracing a shooting style that exists between traditional documentary and narrative filmmaking.

The director added an arthouse touch by shooting in 4:3, a nod to the legendary Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu, but also a practical choice: “It is essential to see the floor,” he says of the toilets.

“Although it was a fictional story, we had a documentary approach. The camera was always on my DOP Franz Lustig’s shoulder — never on a tripod, never on tracks, never on a gimbal or a Steadicam or a crane. This fictional film with the totally fictitious character, Hirayama, was shot like a documentary.”

READ MORE: ‘Perfect Days’ Director Wim Wenders and Kôji Yakusho on Toilets and Tranquility (A.frame)

To make it feel even more authentic, their approach features mostly handheld camera work, and includes a lot of exterior scenes using available light.

The work of Ozu also inspired Wender’s approach, as he describes in a video featurette. “There was this heightened attention [in Ozu’s films] that looked at every object as if it only existed once and only there and he was so attentive to every detail.”

Since each of the toilet buildings are designed by a different architect, “they all have the specific presence,” he said. “And that is also captivating. It’s not as if Hirayama is treating all these toilets as if there were toilets, but he sees them specifically. When you go to these places, you realize the beauty is that they’re all so different, and that each of them forces you to see the world differently. That is a beautiful thing. So, in that way of paying attention to Ozu was ever present.”

Wenders explained to Mascha Deikova at CineD that he wanted to keep the protagonist’s history secret because “this story is not about any possible drama he had in the past. It’s about here and now and the universal humanity of the character,” he said.

“Generally, routine is considered something boring that you do automatically, without really being ‘present.’ To Hirayama, routine means beautiful processes you love doing and that give your life shape.”

READ MORE: The Quiet Frames of “Perfect Days” – Depicting Beauty in the Mundane (CineD)

With NPR’s Scott Simon the director goes further, describing toilet cleaning as a “mythical job.” He said, “You see him work cleaning toilets, and so you easily reduce his job to being a toilet cleaner. But slowly, you realize the richness of his life, and you realize that cleaning a toilet is a strangely metaphoric job.”

Komorebi as a Visual Metaphor

Another metaphor Wenders uses is the Japanese concept of “komorebi.” This term describes the dancing shadow patterns created by sunlight shining through rustling leaves and swaying branches. Every day, during his simple lunch in the park, Hirayama takes pictures of a particular tree with an old Olympus film camera.

“Black-and-white pictures might seem the same to an inattentive viewer. Yet, of course, they are all unique,” says CineD’s Deikova. “The whole concept behind komorebi is that it can exist only for a moment. So, this original passionate hobby is probably the most suitable visual symbol for the main character’s attitude about life.”

As the director explained in another video featurette, photographing Komorebi was a way of honoring the light and the trees. “[Hirayama’s] light photography became an act of saying ‘thank you’ to the light. And the simpler his life got, the happier he was. He became a monk without knowing it. I don’t think in his own thinking he was living the life of a monk — he was just living the life he started to like.”

Wenders says he doesn’t like to feel manipulated in the cinema and struck upon the ideal way to make the sort of film he like in Perfect Days. He explained his philosophy in a video featurette.

“I hate it when I see a movie and in everything that happens, I see this is constructed. Or I’m reminded of [something] 10 minutes later that will have [story] consequences. I hate it when story becomes so obvious that it’s a construction.”

He even finds this in some of his own films like The End of Violence and The Million Dollar Hotel. “I made movies where the little bit of story ruined the entire flow of credibility for me,” he says, “sometimes tiny elements of stories can become giant of disruption.”

But with Perfect Days he strove to create a documentary of a fiction, finding that one of the ways to do this was to film without blocking or rehearsing.

“We basically gave up rehearsing after a while,” he said. “Our documentary approach is a little risky for actors. A lot of actors don’t feel secure if they cannot rehearse and know exactly what they’re supposed to do.

“In my fictional films, I am always so happy if I manage just in one shot here or there [that captures] something that is utterly real and only happens at the moment. I’m ready for a documentary moment to appear in science fiction. On the other hand, in my documentary films, I’m often trying to bring in a little element of fiction because I think that’s how we live. We live in reaction to things that actually happen around us, and we live as a reaction to things we imagine.”

He continues, “The stories that happen are very different categories than the story we impose, let’s say, on an actress in a movie. So Perfect Days became a wonderful mélange of documentary and fiction.”

His hit documentary feature Buena Vista Social Club, about a troupe of musicians in Cuba, is a case in point. The very fact of his making a film helped the world “rediscover” their music and give them a platform to stage their first ensemble performance together at New York’s Carnegie Hall.

“I thought I was making a music documentary when I was filming a real life miracle. I know how in fiction and documentary things cross each other and you can never really define what it is. And that’s the beauty of it. In Perfect Days, I didn’t have to make that effort. It just happened that the routine of that man and his daily work and his going to work in the morning and driving a car and listening to music and coming home and taking a bath in the public bath and going to bed and reading.

“I always had to make an effort in fiction to make it feel like documentary and in documentaries to make them feel like fiction. But here it suddenly happened just on its own. Maybe we had created the conditions that that enable fiction and documentary to go so well together.”

Yakusho’s performance is largely silent but he is given a soundtrack to his mind. Often, the film finds him driving the streets of Tokyo listening to the Velvet Underground, the Rolling Stones, and Nina Simone — a soundtrack of Wenders’ own favorite music from the ‘70s and ‘80s.

“The songs are very much part of the storytelling process, Wenders tells A.frame, “to the point that we put them into the script when we wrote it. For instance, the lyrics to Nina Simone’s ‘Feeling Good’ were on the first page of the script. They were not even intended to be used in the film.

“For me, they described how I imagined this character, his philosophy, and his way of living. They were my prologue. It was only in the end that I realized they were the best way to end the film.”

Next, Watch This:

Why subscribe to The Angle?

Exclusive Insights: Get editorial roundups of the cutting-edge content that matters most.

Behind-the-Scenes Access: Peek behind the curtain with in-depth Q&As featuring industry experts and thought leaders.

Unparalleled Access: NAB Amplify is your digital hub for technology, trends, and insights unavailable anywhere else.

Join a community of professionals who are as passionate about the future of film, television, and digital storytelling as you are. Subscribe to The Angle today!