TL;DR

- AI isn’t necessarily your friend or your foe. It’s the basis for a new set of tools that creatives can use, if they choose to explore its potential.

- Photoshop and other editing programs have utilized versions of AI tools (e.g. Spot Healing Brush) for much longer than the general public has been using the term “AI.”

- One way of looking at AI is to consider the idea that all art, all creativity is in a sense generative. Large language models are in many ways modeled after the way humans view the world and create things in it.

- We may be entering the age of curation. AI will remove barriers to creation, but that doesn’t mean it will generate content with vision or good taste, which may be what differentiates creatives in this new art economy.

Is your general attitude toward technology predictive of your sentiment toward AI? Maybe.

That’s one of my takeaways after watching friends and colleagues Frederick Van Johnson, Pratik Naik, Doc Rock, and Pye Jirsa discuss AI and the future of digital storytelling.

First, it’s important to establish that no one in this conversation is a technophobe nor an AI-disastrist. In fact, Naik says that he came to photography via his love of technology and gear and that same enthusiasm has helped him to embrace AI tools.

“When AI started to slowly roll about, it brought back this full circle moment, where I realized that I need to go back and start embracing technology and staying on top of that to ensure that I can bring my vision to life,” Naik says.

In the world of Midjourney and DALL-E and more, Naik says, “Now there’s less and less of a barrier in order for us to actually show what’s in our mind. And that’s opening up a whole other spectrum of people and bringing them into this visual and digital art side.”

Doc Rock agrees, noting that AI tools are in a long line of technology that have helped people overcome gatekeepers who’d prefer certain arenas to remain rarified and inaccessible. AI, Doc Rock says, now “makes it so that anyone who has an interest in the process can” participate, and he thinks that increased accessibility to storytelling tools will be good for humanity.

However, Naik doesn’t only see blue skies ahead. He understands that disruption will lead to job losses for some: “I’m excited to see where that leads us but also, understand, very scared as well for creatives, especially when it comes to jobs, when it comes to, you know, being able to seek out the people who actually have a talent of doing everything manually and seeing how good they are at understanding the tools that we’ve grown up with, versus somebody who’s just come into the field and typed a few prompts and got something really beautiful.”

Doc Rock answers fears about AI taking away opportunities by focusing on the continued human involvement: “This is what a lot of people are misunderstanding about the AI. The AI is not this nebulous cloud of nothing. It has been backfilled with actual knowledge from actual people who actually wrote all this stuff.”

Jirsa predicts creatives will take on a new role: “I think humans, over the next 10 years, our job is going to be curation. Our job is going to be not so much the technical skill, but curating the experience. But at a certain point, I do believe it comes down to just plain authenticity.”

Of course, that doesn’t mean those who ignore technological advances are in the clear. Doc Rock says, “I think if you’re worried about your job, I will give you my favorite line ever. AI will not take your job, but somebody using AI absolutely will.”

To mitigate that, Doc Rock says, creatives should try out the tools and get firsthand experience before declaring themselves in the anti-AI camp. It’s important, at a minimum, to have a general understanding of what you’re afraid of and why, he thinks.

Naik encourages us to keep “your mind open to the possibility [of AI being helpful], so that if in the future, you need to use it, you have it.”

AI FOR GOOD

Jirsa is excited about using AI tools to automate or decrease dull tasks. He says he’s excited about “workflow possibilities” and eliminating “the things that we don’t necessarily want to be doing,” citing color grading as one tedious example.

Naik says his wife, fine art photographer Bella Kotek, is already putting AI to good use for her work.

“One of the things that like Midjourney has enabled us to do is actually cut down on production time,” he explains. “So for instance, instead of actually taking the model and going into the woods, we can actually shoot it in studio, use Midjourney to create very elaborate backdrops and composite it, saving a lot more production time than actually going into the space, trying to find the exact, perfect location.”

And in his own professional life, Naik says AI has rescued photographs he’s taken and cropped for social media, bringing new possibilities to life via upscaling.

DIGGING INTO THE DEBATES

But how is AI likely to affect the value of our art, or our understanding of what art is? Will we differentiate between purely human-created and AI-generated art? Maybe.

Naik cites “AI Drake” as his turning point from believing that humans will continue to value the effort of making art. He thinks the end product is really what will continue to matter, not the process of creation.

“There is no fighting against [AI-generated art] because the result is so freakin’ good. And it’s only going to get better,” Jirsa says.

He realized much of these debates amount to inside baseball. “Most people probably don’t care. In the long run in our little bubble, we care because we are artists,” Naik predicts. “But for a lot of people out there, the general public, as long as he gets that final goal in a shorter amount of time, that is ultimately what matters.”

But Naik doesn’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing for creatives and for art. “In this overarching conversation, the vision, and curation, is what is going to stand out amongst everything. So we need to really harness that [AI is] bad news for people who have bad vision and horrible tastes.”

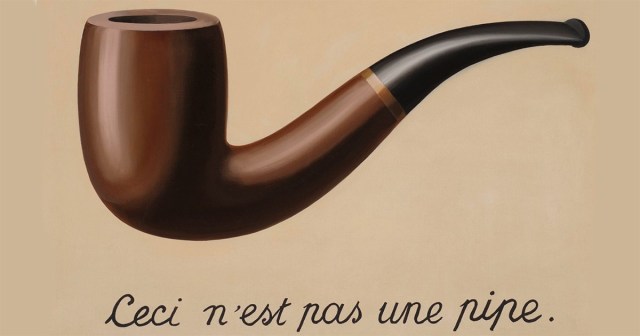

Van Johnson notes that these conversations aren’t really new. The specifics have changed, but the concerns haven’t. From the dawn of photography, every advance has had detractors who say that new tools cheapen the art, whether going from black-and-white to color, adding in Photoshop augmentations, even shooting RAW vs JPEG files.

Besides, Naik argues, “ AI has always been in our tool set. Why are people complaining now? For example, we’ve always had the neuro filters in Photoshop. People never really said much. Then we’ve had the Spot Healing Brush, which is AI driven… but doesn’t make it any less ours.”

We’re “rearranging chairs for no reason,” Van Johnson says, “because the bigger picture is the content.”

But what about the role of ethics here? Is it really OK to use AI to emulate a certain style?

“A human can learn how to paint just like Picasso; you could spend a lifetime figuring it out. And now you can do it, the machine can do it much quicker, does it make the machine wrong?” Van Johnson asks. “Because it can do it faster? I don’t know.”

Jirsa is in the camp that believes very little, if any, artwork is truly original. Even before the advent of AI, he says, “every piece of artwork was already generative. It was already an amalgam of like, everything that you had seen.”

As a photographer, Jirsa says, “I’m just synthesizing everything that I’m seeing and putting my own spin on it.”

Naik agrees: “Subconsciously, we’re just a large language model that doesn’t create the source,” meaning the things and art that have influenced us as artists and creatives.

Maybe our future isn’t so different after all.