TL;DR

- The third episode in Season 2 of FX anthology “Feud: Capote vs. The Swans” travels back to 1966 for Truman Capote’s high society New York ball, which is recreated in the style of a documentary that was never actually shot.

- Director Gus Van Sant shoots in the style of Albert and David Maysles and other mid-1960s documentarians who practiced the Direct Cinema aesthetic: black-and-white, handheld, favoring immediacy and reportage over gloss and precision.

- The Maysles did spend time with Capote in 1966, filming documentary short “With Love From Truman,” but it had nothing to do with the ball.

- Producing a faux documentary gave Van Sant the freedom to run around with a handheld camera, and allowed viewers to see the Swans’ many layers of masks.

The third episode of Season 2 of FX anthology series Feud: Capote vs. The Swans travels back to 1966 for Truman Capote’s “best party ever.”

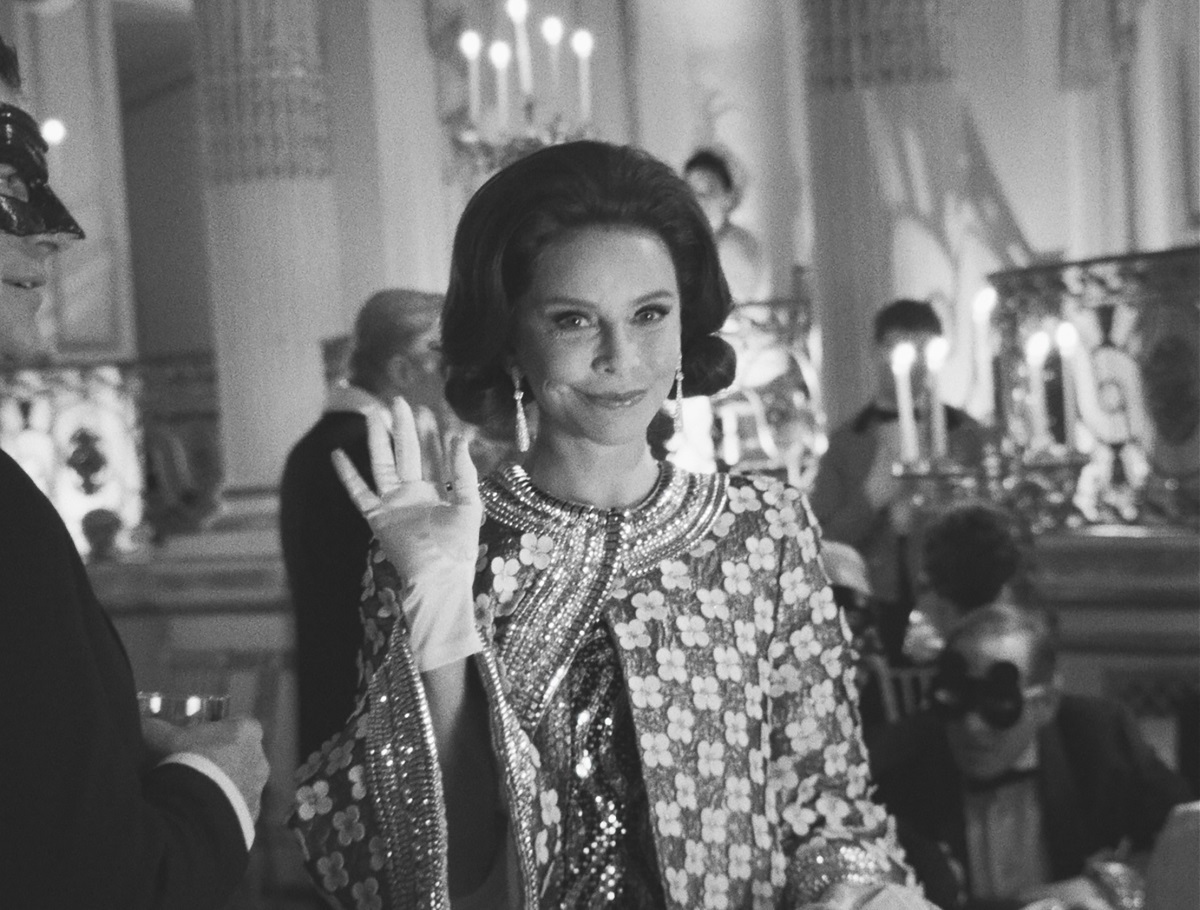

“Masquerade 1966” relives the legendary Black and White Ball hosted by the infamous writer at New York City’s Plaza Hotel — a lavish event boasting a guest list that included everyone from Frank Sinatra and Andy Warhol to Lauren Bacall, Ben Bradlee, the Kennedys, the Agnellis, the Vanderbilts, and the Astors. “As spectacular a group as has ever been assembled for a private party in New York,” according to The New York Times.

Director Gus Van Sant and showrunner Ryan Murphy present the hour-long episode as a black-and-white documentary of the party and Capote’s (Tom Hollander) weeks of preparations for his big night.

At its heart, it’s a flashback episode, with the Swans — Babe Paley (Naomi Watts), Slim Keith (Diane Lane), and Lee Radziwill (Calista Flockhart) — seen in various states of anxious planning. Creating even more drama, two of the high society Swans are under the impression that they would be the event’s “guest of honor.”

The documentarians catching this all, though rarely glimpsed, are depicted as real-life filmmakers Albert and David Maysles. But no such Maysles documentary was ever shot, let alone released. “It was an invention of Ryan [Murphy’s] to pretend like Truman hired somebody to shoot the ball, and then decide to not to go through with it at the end,” Van Sant tells The Hollywood Reporter. “So that was our concept, and our footage that we shot was supposedly their unused footage.”

As THR’s Mikey O’Connell points out, there is a seed of truth here. The Maysles did spend time with Capote in 1966, filming documentary short With Love From Truman. It just had nothing to do with the ball.

READ MORE: ‘Feud: Capote vs. The Swans’ Director on Dramatic Liberties Taken for Black and White Ball Episode (The Hollywood Reporter)

“That was an invention,” Van Sant confirms to Joy Press at Vanity Fair. He did watch footage from the short film the Maysles shot of Capote when he was younger, but creating a faux-documentary gave Van Sant the freedom to run around with a handheld camera, and allowed viewers to see the Swans’ many layers of masks.

READ MORE: Feud: Capote vs. The Swans Digs Far Below the Surface (Vanity Fair)

But though this peek behind the scenes is imagined, “it feels oddly real—like watching never-before-seen footage unearthed from an archive,” according to Coleman Spilde of The Daily Beast. “The episode is a fine example of how to meld past and present, fiction and reality, for something unique.”

Van Sant explains the aesthetic he deployed, saying that in the ‘60s, cinematographers were freeing themselves of the tripod.

“It’s been emulated to the point that now it’s our standard movie style, which is handheld. And handheld today means, like, jerk it around on your shoulder and move it. The people in the ‘60s were trying to hold it really still. They were also trying to get the action, so that was one little aspect of emulating their style. They weren’t trying to make it bumpy, they just…didn’t have a tripod!”

Matt Zoller Seitz at Vulture calls it “the stylistic peak of the series” and talks to Van Sant about creating it with DP Jason McCormick.

“I’ve watched the work of a lot of documentarians, particularly ones who were part of the same movement as Albert and David Maysles,” Van Sant relays. “There was also D.A. Pennebaker, and Frederick Wiseman and Richard Leacock. The films they made were always fascinating to me. They were informing the French New Wave, partly, and by the 1980s, their work influenced MTV videos, as well as films like Oliver Stone’s JFK, which utilized MTV-style camerawork that was emulating the work of documentary filmmakers from that period.”

The director adds that if you construct reality properly, it really doesn’t matter where you put the camera. “If it’s a reality that makes sense, you could shoot it from the corner of the room with your phone. That’s what those documentarians were doing: They went to a location and put themselves someplace, and it was usually the wrong place in relation to where the action was going to be, so they’d have to zoom in to get to the shot they needed. Or they’d try to run over there. A lot of times they got a bad shot. But it was the action you were looking at anyway. You can kind of force yourself into their situation.”

READ MORE: Gus Van Sant’s Maysles Masquerade (Vulture)

Van Sant does in fact sneak in a few shots from the actual event shot by newscasters of the arrival of some of the guests. And there was no shortage of film of Truman Capote to help recreate his character.

The director is no stranger to experimenting with form, often in stories that meld reality and drama whether giving William S. Burroughs a supporting role in Drugstore Cowboy, or interpreting the life of HarveyMilk (Milk), or shooting Elephant and Last Days, which are reactions to Columbine and the death of Kurt Cobain but not conventional docudramas. His most formal exercise was remaking Hitchcock’s Psycho shot for shot.

“I always try to make a story conform to the reality as I know it,” he told The Daily Beast. “When I first started out with Drugstore Cowboy, I was putting so much emphasis on blocking. I ended up doing it in the way I understood Stanley Kubrick did his filmmaking: He would work on a scene first and would figure out the shots afterwards. After that, I started working in that manner,” he said.

“As I got more familiar with my cinema, the blocking started to become more and more complicated, because I realized that anything that happens in reality defies the logic of how you would block it in visual fiction. Even with something that happens in a simple, given space, like a convenience store, the way people move and what they do is very surprising.

“If you were to shoot a basic interaction between two people in a convenience store with your phone and then watch it a couple of times, you’d realize the blocking of reality is quite unexpected. People might enter and exit before they even do anything! Odd things happen all the time. If you can capture those moments and use them in your fiction, you can represent reality in an almost spooky way.”

He adds in the same interview, “Emulating different forms to show different things has always been something to work on, like having a recipe to make. We were doing the same kind of thing on the third episode of Feud but with the films of the Maysles and D.A. Pennebaker.

“We were trying to approximate a documentary of the Black and White Ball so we could see what it would have been like to capture the black-and-white ball, as opposed to explaining it cinematically. It was an experiment. We were emulating films that existed. Their chaos was inspirational.”