TL;DR

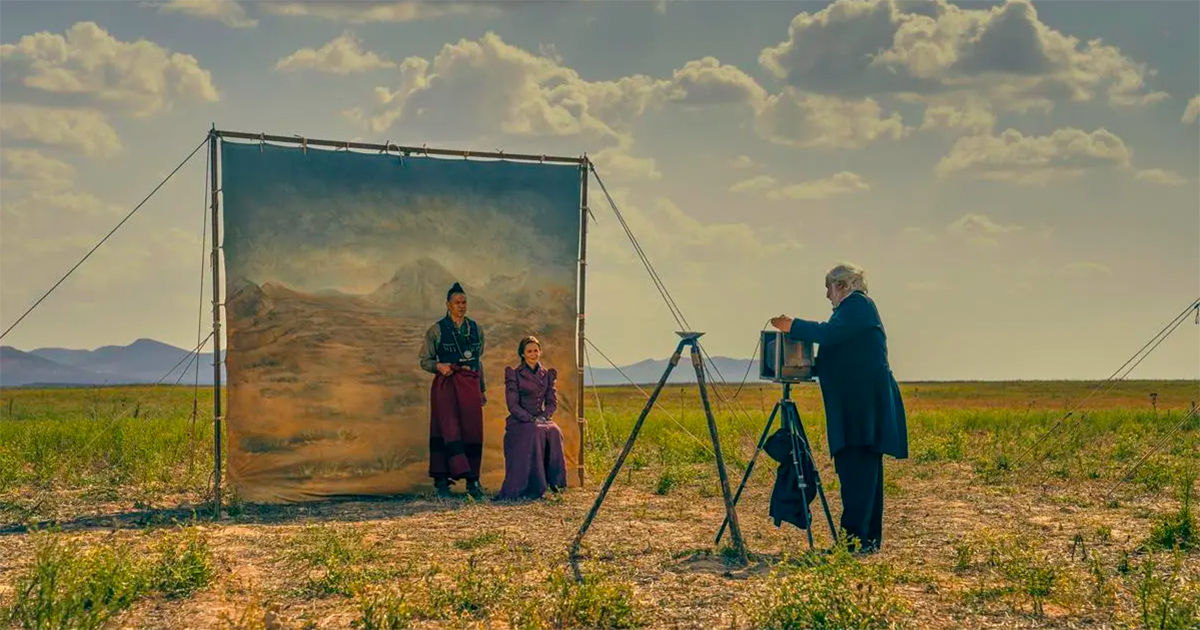

- Cinematographer Arnau Valls Colomer created a co-production episodic Spaghetti Western, filmed in Spain in the Castilla-La Mancha region and the Castile and León region.

- The English is classified as a Spaghetti Western while paying homage to the classic Western style.

- Valls Colomer shared how he would pull references and think about how the original cinematographers of this genre would film the scenes.

Co-produced by the BBC and Amazon Prime Video, The English is an episodic about the multinational land grabs in the American midwest just before the turn of the 20th century. NAB Amplify spoke with Arnau Valls Colomer, the sole cinematographer for all six episodes.

When Valls Colomer read the script for The English, he was tempted for a second to pursue a new way of shooting Westerns: a reinvention. But the production veered away from reinvention to more of an homage. Valls Colomer explained the thinking: “We were tempted to reinvent but decided to make an homage to the classic imagery of the Western but to do it in a modern and contemporary way. We’re shooting digital but didn’t want to create an old or vintage look, it needed to be cleverer than that.”

The show would be shot in Spain, but not in the searing heat of the Almerían deserts where many Spaghetti Westerns (like The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) were shot. They needed areas that would more resemble the journey Emily Blunt’s character makes; from New Orleans to Nebraska.

Castilla-La Mancha is a region in central Spain southeast of Madrid, and further north is Castile and León, which has the high plateaus ringed by mountains. Both would make believable stand-ins for the wide-open spaces of Nebraska, Wyoming and Kansas.

Adding in some clever framing, beautiful silhouettes, and a few digital set-extended mountains would complete the disguise.

But also essential to the look of The English was the way it was shot to tell the story and live with the challenging shoot schedule. They decided to use a static camera, partly due to the use of heavy Panavision anamorphic lenses and accessory-laden Sony cameras, which were hard to move quickly, but also to create an observing aesthetic that was witnessing the action and not following or chasing it.

“The style was composed and quiet but with lots of angles, we had three cameras running at the same time. But it doesn’t look like a three-camera show because the shots are so static. The style becomes the language of the shoot suiting the dialog scenes particularly as they’re elevated with that lack of movement,” Valls Colomer says.

“We realized how good the static style was for us and pushed it even more finding it a very effective way of shooting six hours in 90 days.”

But he also wanted the Technicolor look. “The lighting should also be an homage to the classic Western so we played with the Technicolor blue of the sky and tried to find the right skin tone that looked orangey like the Westerns but not too much so the audience would understand it was a modern image.” Valls Colomer found a similar simplicity in the color grade, trying not to use some of the techniques like masking that weren’t around a few decades ago.

But if you wanted the iconography of the Hollywood Spaghetti Westerns, it’s all there, generally romanticized but beautifully done; your television has never looked so gorgeous. “The Western is purely cinematic anyway and doesn’t exist in the real world. It’s fairytale really so you can do whatever you want,” Valls Colomer commented, referring to the freedom he had to shoot from director Hugo Blick.

This included shooting night scenes under the stars using day-for-night shots composited against studio-controlled action scenes for the actors. “There were a couple of scenes where the two leads are talking underneath the stars with just a candle next to them. As a cinematographer when you read these scenes you wonder how you are going to make them believable with a magic quality to them.

“I actually imagined what the original cinematographers would do back in the day of the Westerns. They would build an enormous set and paint the background with beautiful stars. But I wanted to see that with the enormous landscape lit by the stars, so how do I do it without having a backdrop?” Valls Colomer said.

“We also wanted that feeling of infinity where you would see the landscape extends so much. So we built a set and put a blue screen on it. We then shot the backgrounds with day for night effects, but the actors were in the studio where I could control the light.

“This was the basis of our approach and led our thinking; as in how did the cinematographers of the day achieve the shots and what would be the new version of that with the latest technology?”

As most drama-driven episodic are now produced, The English was shot like a movie. A 90-day shoot in Spain extending from late spring 2021 through the end of the summer also included a COVID break. But Valls Colomer explains that the Spanish seasons dictated the shooting schedule. “Late spring and early summer work very well in Spain for the exteriors, and then when August arrives we mainly shoot interiors because of the harsh and high light.”

But the Spanish magic hour is about 8:30 PM for master shots, which considerably changed their film schedule. “Normally what you do on films is you start on a wide shot and then do the close-ups. Here we did it the other way around, during the day we’d do the close-ups with dialog scenes where we would light them and then knowing that the end of the day would be an amazing for wide shots, we’d do that.”

Shooting anamorphic for television is no longer forbidden, and in fact different broadcasters or streamers indulge in aspect ratio tricks to find a hook to keep their audiences interested. But for the way Valls Colomer shot The English, his use of embedded grain proved a sticking point for the BBC and their online service, iPlayer.

“They did fight against the grain as I was applying a texture which uses grain according to the exposure,” he said. “It’s not like one layer but it reacts to the light, I use it on every film. The BBC wasn’t sure about it but I explained the process and they were fine with it.”

Shooting with Panavision vintage anamorphic Primo lenses harkened back to older Westerns, but Valls Colomer mixed them with smaller and lighter C-series anamorphics. As the shoot was static, they could use these big lenses without moving them too much. But they also had some special features. “They had the bokeh and the flares and are very well built so they don’t distort that much,” the DP said.

“I was shooting in a very old-fashioned way, putting in a lot of light and making the lens perform, shooting in a way as if I was working on negative in the 1950s. So, a good T-stop and not wide open, a very old-fashioned style.”

The lenses also had breathing effects that changed the shape of the bokeh depending on where the focus was. “It moves the background bokeh with those old lenses and we used it a lot for gun close-ups and things like that.”

The cameras were all Sony VENICE using the Super 35mm sensor option at 4K, which Valls Colomer found as the perfect foil to the vintage glass. “I did some tests and it works very well with these old lenses to have a very sharp sensor. We found a sweet spot with both technologies,” he said.

“Even now I would shoot the same way and I know there are new cameras out like the ARRI. The combination works well for me.”

Valls Colomer received great plaudits for his work on The English, not just from his contemporaries but also film fans who loved what he’d done. It has certainly raised his profile, and he recently shot a Penelope Cruz movie, En Los Margénes (On the Fringe), and the secretive Apartment 7A, a prequel to Rosemary’s Baby with Ozark breakout star Julia Garner.