TL;DR

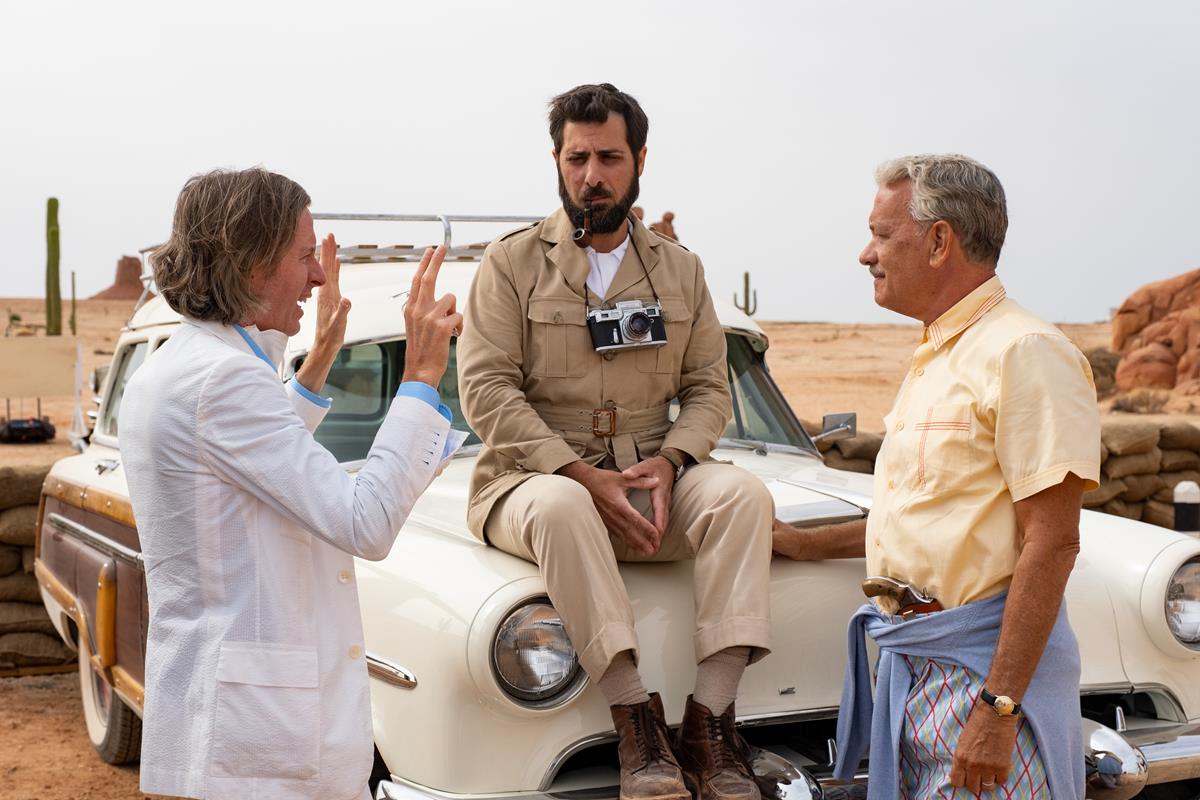

- “Asteroid City,” Wes Anderson’s new film, is set in a midwestern desert and involves a group of scientists, military personnel and students who encounter an alien at a meteor crater.

- Cinematographer Robert Yeoman faced challenges shooting under bright, direct sunlight in the desert, maintaining consistent light in day exteriors, and working with a minimal crew and no artificial lighting.

- Yeoman used techniques from early filmmakers, such as shooting outside with some bounce to compress the contrast range and using sunlight for interiors.

- Anderson’s preference for single camera setups and choreographed camera movements contribute to his distinct filmmaking style.

- Despite Anderson’s films being meticulously planned, Yeoman emphasizes the importance of flexibility and spontaneity on set, pushing himself to create visually interesting shots.

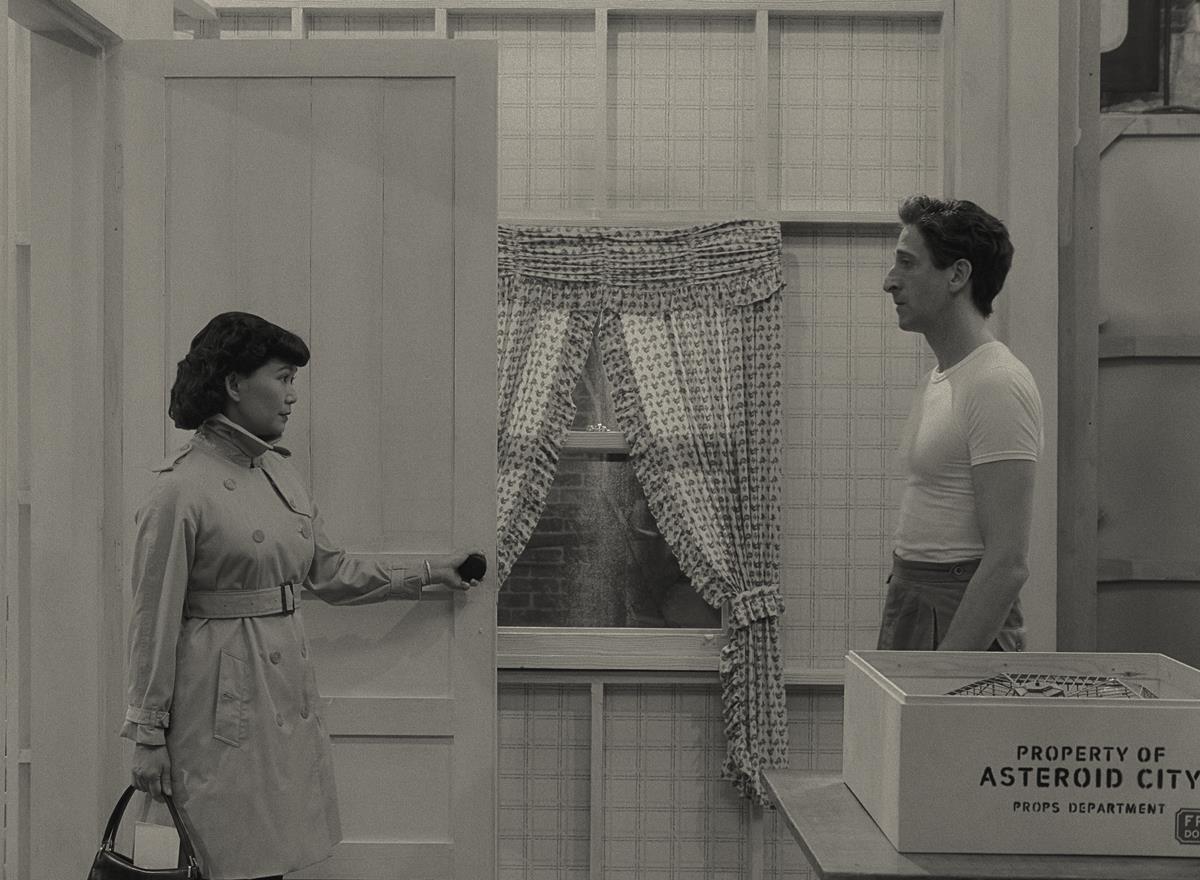

Pictured above: Jason Schwartzman as “Augie Steenbeck” and Scarlett Johansson as “Midge Campbell” in Wes Anderson’s “Asteroid City,” a Focus Features release. Credit: Courtesy of Pop. 87 Productions/Focus Features

Wes Anderson’s new film Asteroid City is set in a Southwestern desert in the 1955, but really in a place that could only exist in Anderson’s imagination.

The story, involving a number of scientists, military personnel, and “Junior Stargazer” science students, finds the group gathered at giant meteor crater for a ceremony honoring the children’s inventions, only to find everything thrown into chaos when an actual alien arrives.

Shot in the flat desserts of Chinchòn, Spain — a small town not far from Madrid — cinematographer Robert Yeoman, ASC had to face a lot of things that people in his field generally try to avoid like the plague: Shooting under the kind of bright, direct sunlight that tends to yield blown out highlights and extremely deep shadows.

But Anderson’s entire aesthetic and approach to filmmaking would make it highly unlikely he would ever try to make life easier by shooting on a soundstage (or, God forbid, in front of a volume!).

Yeoman, who has shot all of Anderson’s live-action films since his directorial debut Bottle Rocket, decided to address the situation in the way the earliest filmmakers did. They shot outside with just some bounce to compress the contrast range somewhat and they used sunlight for interiors, too.

As Yeoman told Jim Hemphill at IndieWire, “I knew that inside locations like the diner would need light, so I just asked if we could put skylights in the diner and any building where we knew we were going to be shooting day interiors.

“[Production designer] Adam Stockhausen put skylights in and we covered them with very soft diffusion material and it worked out beautifully. We never used any lights, and that was Wes’ dream,” he said.

“It was a constant challenge maintaining consistent light in the movie’s many day exteriors. On other movies, I would be tempted to bring in some big lifts and put giant silks up to soften the light, but it was too windy out there in the desert.”

The filmmakers watched some movies shot in similar locations with minimal amounts of artificial light, such as Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas, shot by Robbie Mueller, and the DP started to feel comfortable leaning into the approach.

He also explains to Hemphill that it’s not just lighting that Anderson likes to keep simple, it’s also crew. And the virtual elimination of lighting units went a long way to keeping things light and nimble.

“Often,” Yeoman says, it was “just [Anderson], myself operating, a focus puller, a second AC with a slate, a dolly grip and a boom guy,” While the director does use a small, handheld monitor as a small concession to 21st century convenience, “he sits next to the dolly [and] watches the actors.”

READ MORE: ‘Asteroid City’ Has the Precise Camerawork of a Wes Anderson Film — but Now in Desert Sunlight (IndieWire)

From the time Anderson directed the animated Fantastic Mr. Fox (shot by Tristan Oliver), he fell in love with the idea of creating animatics and, on his next live-action film, he swapped out the storyboards he’d previously relied on for the more fleshed-out moving approach of the animatic and he’s never looked back.

In an interview with Tim Molloy at MovieMaker Magazine, Yeoman notes that while Anderson’s films are famously planned out in great detail, with camera positions and movements designed into the animatics, he still likes to show up to the set with some sense of flexibility, rather than having an exact plan for everything that happens that day.

“‘I want to be open to something that spontaneously might happen on set,’” he explains. “‘I do make my own diagrams of camera positions and lighting ideas that I share it with my gaffer. But there’s always some nervousness when I show up in the morning, because I want to push myself to that place where you’re not sure about things.

“When I feel totally secure and confident and sure, I might lapse into something a little more conventional, whereas if I keep my edge, I might come up with something that’s a little more interesting visually.’”

The cinematographer is very supportive of Anderson’s single camera approach, despite the fact that second, third and even fourth cameras are very common on movie sets. “I find that we can often move faster with one camera than with two cameras,” he says.

“Two cameras often means you’re getting coverage. Coverage is great, but with Wes, every shot is specific for the particular moment that he wants. A lot of great directors have a distinct style because they believe there’s one place to put a camera and to tell a story, and that’s the place we’re going to commit to.”

READ MORE: Asteroid City Cinematographer Robert Yeoman on Why He and Wes Anderson Never Settle (MovieMaker Magazine)

Of course, a Wes Anderson movie wouldn’t be a Wes Anderson movie without enough choreographed camera movement to make a Max Ophüls film feel like Andy Warhol’s Empire in comparison. “There’s a scene where Jeffrey Wright is giving a speech,” the DP told Esquire’s Tom Nicholson. “Wes was eager to do it all in one shot, he [Wright] walks to one end of the stage and the other, so we had to make a track that would go sideways and in and out — typically you might use a Steadicam or a Technocrane to do a shot like that. But because Wes is so precise on the framing and compositions, even if you’re off a little bit, that’s not acceptable.”

READ MORE: Wes Anderson’s Cinematographer Has Some Thoughts About Your TikToks (Esquire)

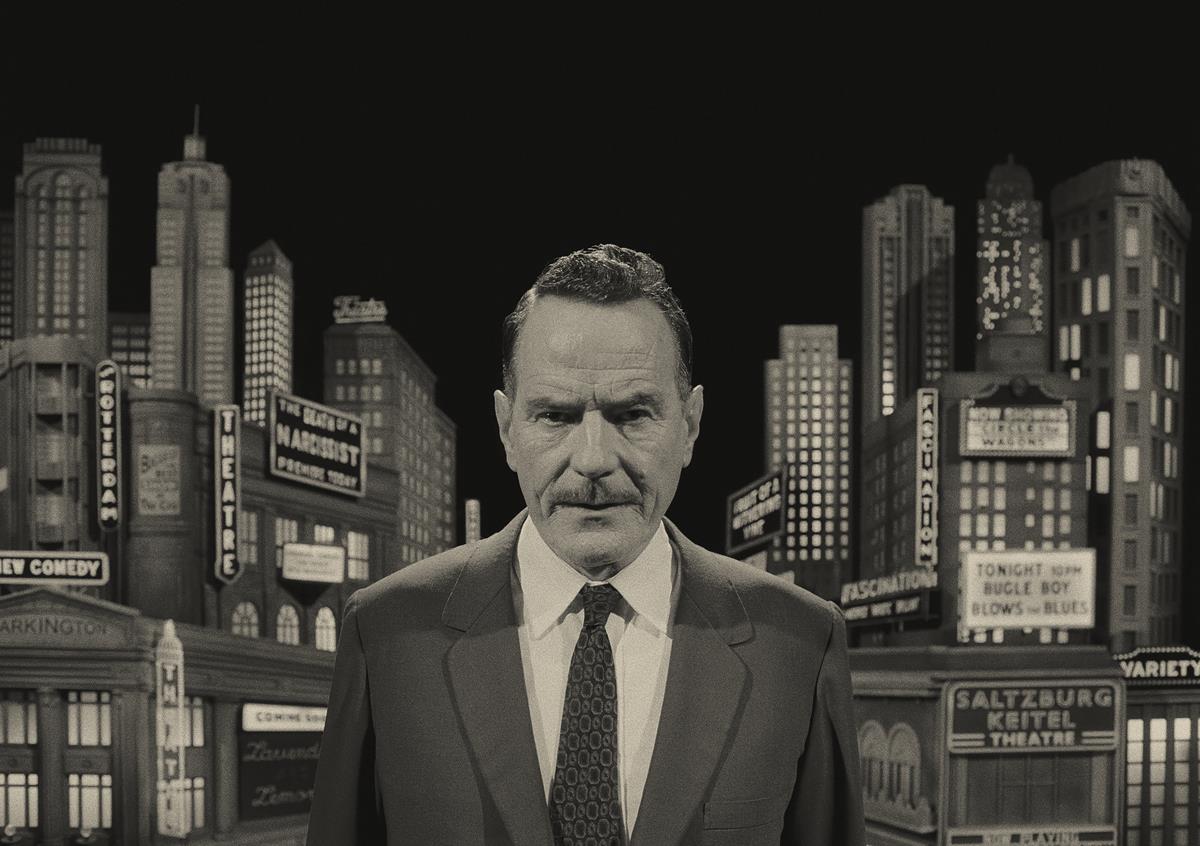

To continue the conversation about camera movement, it would be appropriate to cite what may well be the only profile of a dolly grip ever to appear in The New York Times. Written by Melena Ryzik, the piece about Mumbai-born Sanjay Sami, who started out working on Bollywood movies and has been designing track and pushing and pulling dollies on Anderson’s movies since 2006, references a scene in which Adrian Brody makes his way “through a long theater space in an exquisitely detailed choreography of sets, props, walls, actors, dialogue and camera,” which, as Brody explains to Ryzik, “has to come off of a set of tracks and then be loaded seamlessly onto another set of tracks and hit numerous precise marks at very specific timings.”

“The thing I love is, with Sanjay, we essentially are using the same equipment that we might have used on a movie 75 years ago,” Anderson told Ryzik, “but we’re arranging it in a way that it hasn’t been arranged before.”