TL;DR

- Mixed reality — or spatial computing — is still an experiment, but Apple has spent billions of dollars developing the Vision Pro using passthrough technology that allows the wearer to see the real world while wearing the goggles.

- The Apple Vision Pro may be a marvel of modern industrial design, but what will the killer app for its mixed reality be, if there is one at all?

- The psychological effects of experiencing virtual and mixed reality for long periods have not been properly examined, but the evidence to date doesn’t bode well, in part because of how socially isolating it can be.

READ MORE: Where Will Virtual Reality Take Us? (The New Yorker)

As Apple releases its new mixed reality system Vision Pro the media tech industry is pondering what it is for. No-one knows the answer, and probably not Apple, but given its track record in defining new categories in consumer electronics, interest in its approach and capabilities are high.

Apple’s entrance into VR has symbolic weight, because the company has had so much influence on computers and phones, Microsoft exec and VR pioneer Jaron Lanier writes in The New Yorker.

Apparently Apple CEO Tim Cook “knows” that VR (or spatial computing) is the future of computing and entertainment and apps and memories, according to Nick Bilton at Vanity Fair.

READ MORE: Why Tim Cook Is Going All In on the Apple Vision Pro (Vanity Fair)

VR has long been an established industrial technology, used for designing cars and to train surgeons in new procedures, for example. It has also been used by artists to explore the nature of consciousness, relationships, bodies, and perception, writes Lanier.

In between the two extremes lies a mystery: “What role might VR play in everyday life? The question has lingered for generations, and is still open.”

Lanier considers the Vision Pro to be a virtual reality device, one that allows users to see the real world around them overlaid with 3D virtual objects. That’s because video of the user’s surroundings are streamed — almost live — and displayed onto a high resolution screen.

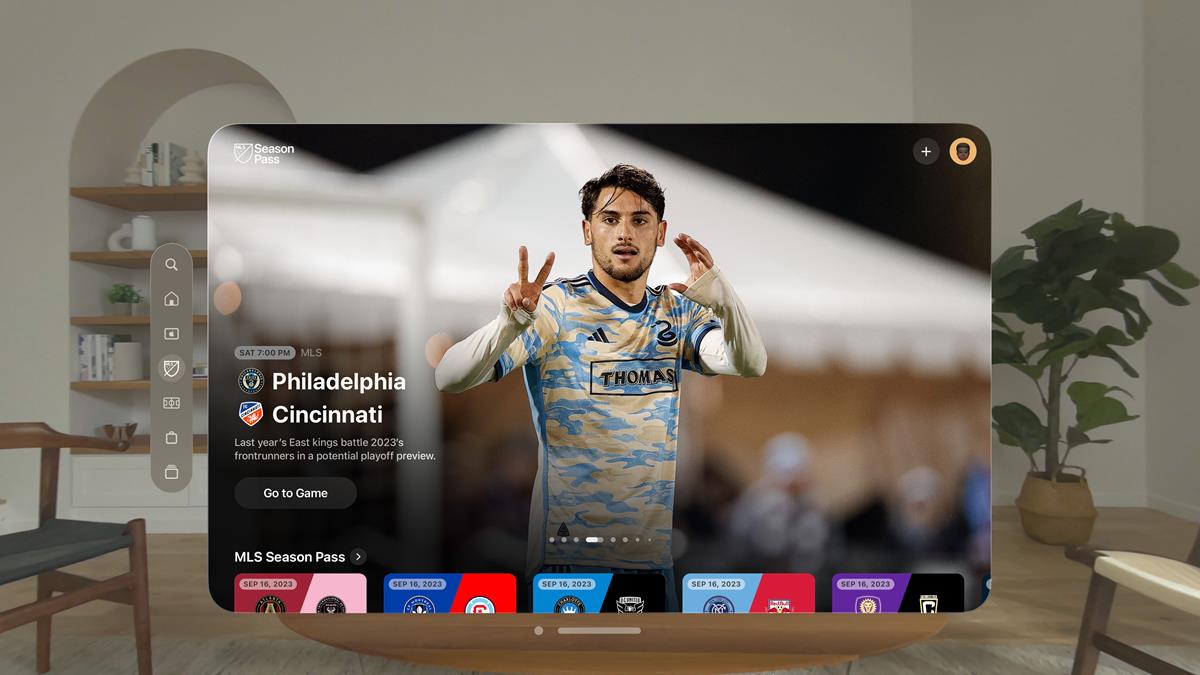

As Shira Ovide at the Washington Post explains, “When you strap on the Vision Pro, you can watch a movie through the screen on your face and see your living room around you. You can pull up a recipe app through Apple’s headset and position virtual cooking timers above your pots as you follow the instructions.”

She says, “But you’re not seeing the real world. You’re seeing a nearly live streaming video of your living room or kitchen with apps superimposed on there.”

READ MORE: Apple’s Vision Pro is ‘spatial computing.’ Nobody knows what it means. (Washington Post)

It’s called real-time passthrough video, and Meta’s $500 Quest 3 headset works the same way.

Director James Cameron explained to Bilton that the imagery in the Apple Vision Pro looks so real because it is writing a 4K image into users’ eyes. “That’s the equivalent of the resolution of a 75-inch TV into each of your eyeballs — 23 million pixels,” he said, later adding that he thinks the product is “revolutionary.”

Bilton listed a number of problems with the product — none of which were insurmountable. For instance, the unit’s $3500 price tag could be subsidized by Apple if it wanted with “as much financial impact as Cook losing a nickel between his couch cushions.”

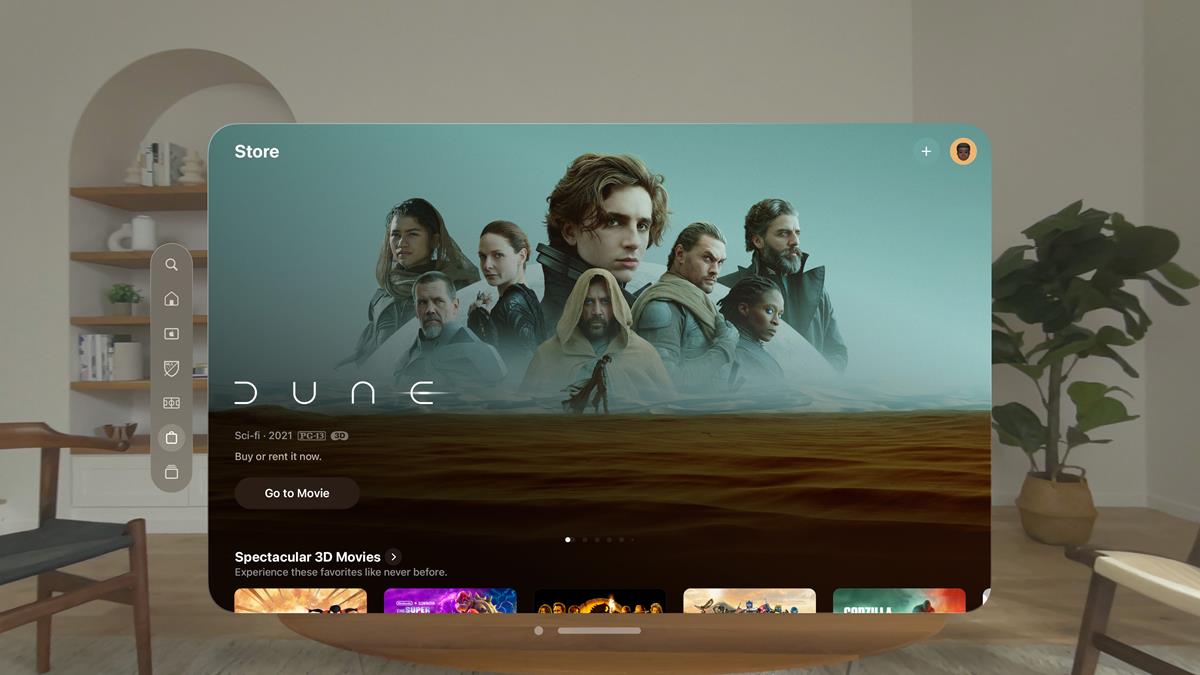

It’s not the weight or the size because V2.0 will improve on this, or how Meta, Netflix, Spotify, and Google are currently withholding their apps from the device: “Content creators may come around once the consumers are there, and some, like Disney, are already embracing the device, making 150 movies available in 3D, including from mega-franchises like Star Wars and Marvel,” Bilton notes.

No, what bothers Bilton about the Vision Pro is just how good the experience is. Clearly wanting to keep getting invites to interview Apple bosses and get behind closed doors previews, Bilton says that every other routine computing experience — and even the actual world round us — pales besides the hyper-real version of it viewed through Cupertino’s new googles.

“In the same way that I can’t imagine not having a phone to communicate with people or take pictures of my children, in the same way I can’t imagine trying to work without a computer, I can see a day when we all can’t imagine living without an augmented reality.”

This is because with the Vison Pro you “actually feel like the person is in front of you and you can reach out and touch them,” he gushes. “I saw the world around me. I didn’t feel closed off or claustrophobic. I left the Apple offices… and when I opened my laptop, a relatively new computer, it felt like a relic pulled from the rubble of a Soviet-era power plant.”

Around 180,000 people have been tempted to buy a Vision Pro in the opening weekend of online preorders, according to figures quoted by Vanity Fair. Morgan Stanley anticipates that sales will ramp up to two million to four million units a year over the next five years, and it will become a new product category for the company. But others, like Apple supply chain analyst Ming-Chi Kuo, thinks it’s going to remain a niche product for some time.

David Lindlbauer, a professor leading the Augmented Perception Lab at Carnegie Mellon University, doubts that we’ll see people talking to their friends while wearing Vision Pro headsets at coffee shops in the near future. It’s simply strange to talk to someone whose face you can’t fully see.

“Socially, we’re not used to it,” Lindlbauer told Vox. “And I don’t think we even know if we ever want to get used to this asymmetry in a communication where I can see that I’m me, aware of the device, can see your face, can see all your mimics, all your gestures, and you only see a fraction of it.”

Lanier notes that research by a Stanford-led team has found evidence of cognitive challenges with such camera-based mixed reality. They shared their findings in a new paper that reads like a cautionary tale for anyone considering wearing the Vision Pro anywhere but the privacy of their own home.

READ MORE: Seeing the World through Digital Prisms: Psychological Implications of Passthrough Video Usage in Mixed Reality (Virtual Human Interaction Lab)

“Your hands are never quite in the right relationship with your eyes,” he says. “Given what is going on with deepfakes out on the 2D internet, we also need to start worrying about deception and abuse, because reality can be so easily altered as it’s virtualized.”

As explained by Vox reporter Adam Clark Estes, a big problem with the passthrough video technology is that cameras — even ones as high-tech as those in the Vision Pro — don’t see the way human eyes see. The cameras introduce distortion and lack the remarkable high resolution in which our brains are capable of seeing the world. What that means is that everything looks mostly real, but not quite.

So, when the headsets came off, it took time for the researchers’ brains to return to normal, so they’d misjudge distances again. Many also reported symptoms of simulator sickness — nausea, dizziness, headaches — that will sound familiar to anyone who’s spent much time using a VR headset.

READ MORE: What wearing Apple’s Vision Pro headset does to our brains (Vox)

Tech analyst Benedict Evans noticed that in videos Apple released to developers last year to showcase what the Vision Pro can do: “Apple doesn’t show this being used outdoors at all, despite that apparently perfect pass-through. One Apple video clip ends with someone putting it down to go outside.”

READ MORE: Vision Pro: What has Apple built, what is it for, what does it mean for Meta, and why does it cost $3,500? Check back in 2025. (Benedict Evans)

Lanier’s concerns run deeper than user experience. He thinks virtual reality apps for the Vision Pro will come from all kinds of companies, and “could agitate and depress people even more than the little screens on smartphones.”

He is also worried about the engineering and support effort it will take to keep a system as complex as this always up to date.

More problematically, Lanier just doesn’t think users are going to want to be in virtual reality for anything more than specific experiences.

“Apple is marketing the Vision Pro as a device you might wear for everyday purposes — to write e-mails or code, to make video calls, to watch football games,” he says. “But I’ve always thought that VR sessions make the most sense either when they accomplish something specific and practical that doesn’t take very long, or when they are as weird as possible,” he says.

“Venture capitalists and company-runners talk about how people will spend most of their time in VR, the same way they spend lots of time on their phones. The motivation for imagining this future is clear; who wouldn’t want to own the next iPhone-like platform? If people live their lives with headsets on, then whoever runs the VR platforms will control a gigantic, hyper-profitable empire.”

But Lanier doesn’t think customers want that future. He says, “People can sense the looming absurdity of it, and see how it will lead them to lose their groundedness and meaning.”

To Lanier, living in VR makes no sense to who we are as human beings. “Life within a construction is life without a frontier. It is closed, calculated, and pointless. Reality, real reality, the mysterious physical stuff, is open, unknown, and beyond us; we must not lose it.”

Discussion

Responses (1)