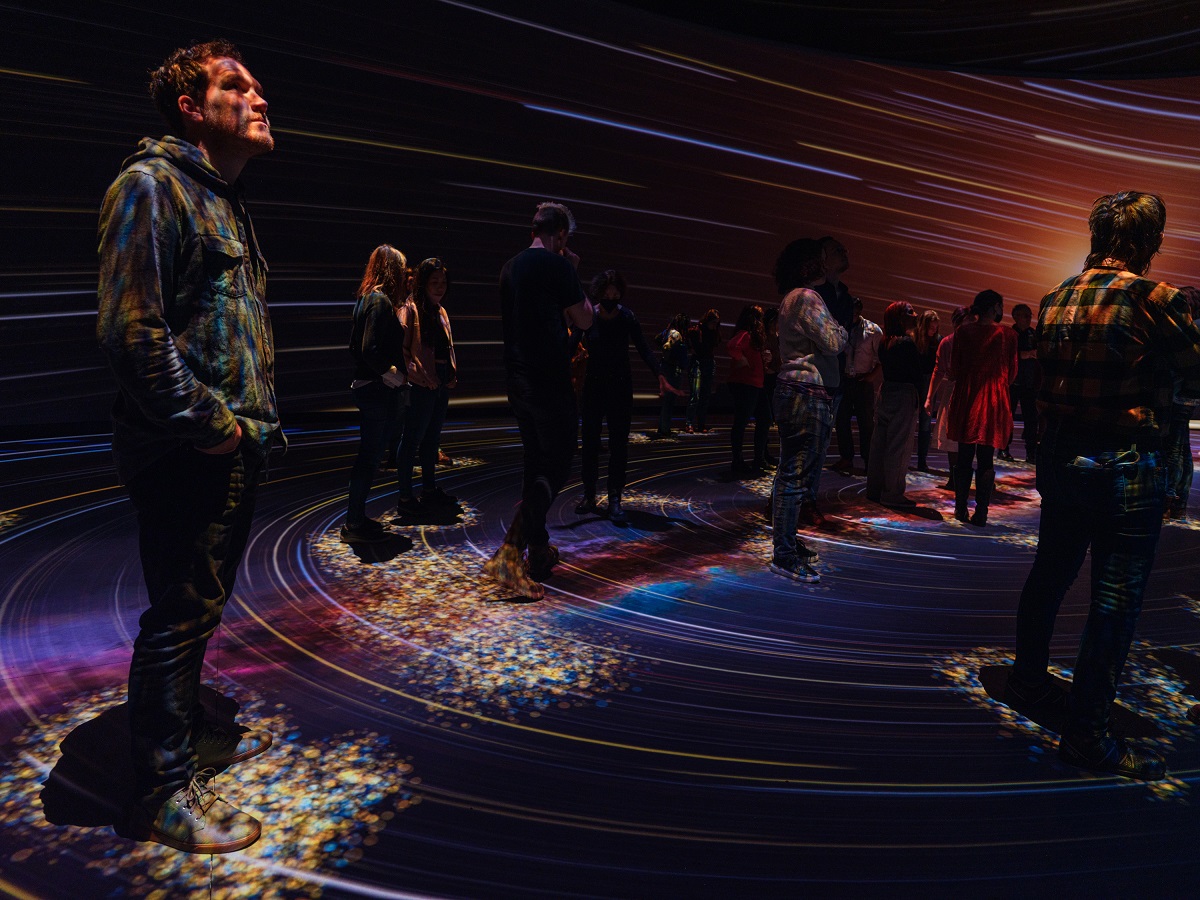

The “Invisible Worlds” exhibit at the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation.

TL;DR

- The American Museum of Natural History in New York City recently launched the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, a new 230,000-square-foot expansion.

- The $465 million project was designed by Chicago-based architecture firm Studio Gang and took nine years to complete.

- One of the key features of the center is “Invisible Worlds,” an immersive exhibit that invites visitors to explore unseen networks of life from the microscopic to the cosmic.

- Designed by Berlin-based Tamschick Media+Space, the exhibit is housed inside a vast virtual production volume nicknamed “the bowl,” featuring 23-foot-high walls that surround visitors with projections at all scales.

The Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, a recent addition to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, stands as a testament to the fusion of modern architecture and innovative design. The 230,000-square-foot expansion was meticulously constructed to bridge the gap along the museum’s western edge, introducing 30 new access points to the institution’s sprawling 20-building complex. The result is a harmonious blend of old and new, extending the museum’s central axis westward from the iconic Roosevelt Rotunda and aligning the fresh facade with the bustling 79th Street.

James Panero, writing at The New Criterion, explains the seemingly impossible problem represented by the museum’s patchwork construction, describing warrens seemingly built with no rhyme or reason. “Anyone who has walked through the American Museum of Natural History might have sensed something was wrong,” he says. “Just go through its Hall of Gems and Minerals, or its Hall of South American Peoples, or its Hall of Pacific Peoples. At the end of each of these long rooms, which were only reached through other long rooms, you found nothing less than a dead end.”

But the reason for the museum’s confusing layout, Panero reveals, was — in a way — by design. “The master plan of this museum, founded in 1869 and first envisioned by Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould in 1872, has never been fully realized,” he notes. “Much like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and other grand 19th century American edifices, New York’s natural-history museum was laid out on a massive cross-in-square plan, which has only been partially built out over time.”

Amid unrealized plans filled with dead ends, the museum’s evolution has only compounded these issues, Panero continues. “What this means is that, over a century and a half after its founding, the street-facing facades and infill architecture of this museum have been created in a progression of styles that have reflected, for better and worse, the ideals of their times.”

READ MORE: The inside-out diorama (The New Criterion)

In other words, the architecture was a hot mess, and the new Gilder Center was specifically designed to undo a multitude of practical and aesthetic sins. But don’t call it a makeover.

Unveiled to the public on May 4, 2023, the center embodies the transformative potential of immersive technology in education. The center owes its existence to the patronage of the late financier Richard Gilder, a philanthropist renowned for his support of numerous New York-based institutions. Its mission is to broaden the museum’s educational horizons, offering additional classroom spaces and a platform to display a greater portion of the museum’s vast collection of scientific specimens and artifacts. The center represents a significant leap in the museum’s evolution, inviting visitors to engage in a dynamic, interactive experience that transcends the confines of traditional museum exhibitions.

Fast Company’s Nate Berg explores the $465 million project, which was designed by the Chicago-based architecture firm Studio Gang, and stretched over nine years to reach completion.

The center “has a rib cage of a facade and a bird bone of an interior,” Berg writes. “The atrium’s walls bend and move to become staircases and bridges, and open up to form entrances to exhibition halls or views through and out of the buildings. It resembles the hollow-but-buttressed inside of birds’ bones sliced open and viewed through a microscope, strong enough to provide structure but light enough to allow them to take off.”

Inside the expansive center, “there are exhibitions on zoology, paleontology, geology, anthropology, and archaeology, as well as a butterfly vivarium and a decidedly of-the-moment immersive experience looking at networks of life in nature at scales both visible and invisible. These spaces all radiate out from a connecting central atrium that is the Gilder Center’s showpiece, which is a swooping, Swiss cheese monolith of raw concrete.”

The walls of the atrium, a soaring, four-story civic space that serves as a new gateway into the museum from Columbus Avenue, “bend and move to become staircases and bridges, and open up to form entrances to exhibition halls or views through and out of the buildings,” says Berg. “It resembles the hollow-but-buttressed inside of birds’ bones sliced open and viewed through a microscope, strong enough to provide structure but light enough to allow them to take off.”

READ MORE: This spectacular new museum could be a skeleton, a cave, or the fabric of the universe (Fast Company)

That “of-the-moment” immersive experience Berg references is Invisible Worlds, both a key feature of the center and a game-changer in the world of immersive exhibitions. It invites visitors to explore the unseen networks of life, from the microscopic to the cosmic, in an unprecedented interactive journey.

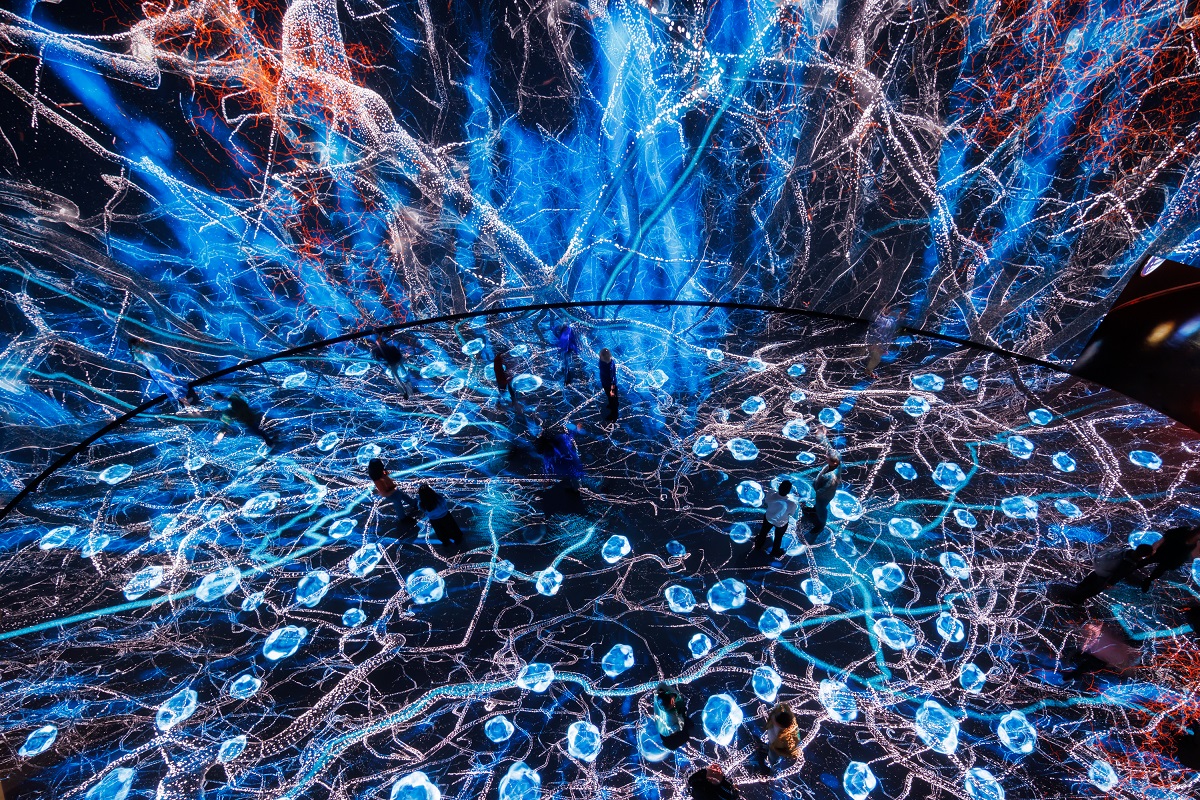

The extraordinary 360-degree immersive science-and-art experience offers a breathtakingly beautiful and imaginative yet scientifically rigorous window into the networks of life at all scales. It was designed by the Berlin-based Tamschick Media+Space (TMS) in conjunction with the Seville-based Boris Micka Associates, who worked closely with data visualization specialists and scientists from the museum and around the world to bring the exhibit to life.

Building on the museum’s iconic habitat dioramas and Hayden Planetarium Space Shows, the Invisible Worlds exhibit takes place inside what looks like an enormous virtual production volume, nicknamed “the bowl.” The space is as large as a hockey rink, featuring 23-foot-high walls that surround visitors with projections at all scales and mirrors at ceiling height suggesting infinity.

A looping 12-minute immersive experience reveals that all life on Earth is interconnected: from the building blocks of DNA to ecological interdependencies in forests, oceans, and cities to communication made possible by trillions of connections within the human brain.

Accompanied by responsive audio, the imagery ranges from LiDAR scans of New York City and airplane-traffic data to 3D renderings of a dragonfly’s nervous system, models of fish schooling behavior, and a map of the human brain. At key moments, visitors become part of the story as their own movements affect the images of living networks depicted all around.

Alex Pasternack at Fast Company takes a deep dive into the exhibit, asking us to “imagine an immersive Planet Earth, or Powers of Ten, built with powerful GPUs, 3D software, and a constellation of speakers and laser projectors that respond to you.”

Moving inside the bowl, visitors see a fungal network branching across the walls and floor. “As you get your bearings, your sense of perspective and scale, you step on one route and water glides along it,” Pasternack writes. “Then you’re floating up to the rainforest canopy, with lemurs and snakes and a giant hummingbird and a leaf in its microscopic glory, and flocks of birds that fly around you on their way north. Next, flying from space down to Manhattan, you see humans’ own digital signals, not unlike those fungal networks, or elsewhere, the webs of neurons that also signal when you step on them. Later, deep in San Diego Bay, a giant humpback, blue in a veil of glowing plankton, emerges from the darkness with a low wail, dwarfing you and everyone else.”

Marc Tamschick, founder and creative lead of TMS, explains to Pasternack how the goal was to use real-world data without pummelling visitors over the head with mountains of tech and science. “If you dig deeper, you’ll find relationships to all the galleries in the museum. And I think people will add their own memories to what they see,” he said, “and then it kind of starts to open the heart.”

Vivian Trakinski, director of science visualization at the American Museum of Natural History, told Pasternack that during the development process she was afraid the experience would be “completely overwhelming,” as she put it. “But when we came in for the first time, it was peaceful, it was contemplative.”

Pasternack calls Invisible Worlds “a feat of modern science communication.” Comparing it to a recent real-world trip undertaken to observe humpback whales off of the coast of Southern California, he says, “It’s hard to describe the vertiginous feeling of glimpsing these majestic animals even at a distance; now I was underwater with one of them, and I wanted to stay there.”

READ MORE: The future of the museum is an empty room that can take you anywhere (Fast Company)

Tim Deakin at MuseumNext asked Tamschick how advancements in technology helped shape the Invisible Worlds exhibit over the nearly seven years it took to complete the project. “We always have to start with the idea. Only when we know what we want to share with the audience do we look at technologies to carry that message. I think that projects should never be driven by the hardware; instead it should always be driven by the content,” Tamschick said.

“That gives us greater ability to choose how we want to progress the project. In saying that, we are also fortunate in our line of work to collaborate with experts who can see what technologies are coming in the future. In this instance, that helped us to understand that what we wanted to visualize was only going to become more precise and more high quality as the project developed.

“We also planned the project in such a way that, if the technology improves significantly in the next five years, the museum could simply upgrade the hardware but deliver the same content.”

For Tamschick, the aim of Invisible Worlds is to create an environment visitors can explore in an authentic way. This contrasts with other immersive experiences that serve as contemplative experiences or learning opportunities. “We hope that people will connect with topics they didn’t know they were interested in before,” he says. “People may never have considered what happens when you shrink to the size of a molecule or sink to the depths of the ocean.”