With actor, director and performance capture artist Andy Serkis brought on to direct Venom: Let There Be Carnage, there’s no surprise that raging personality disorders were high on the agenda. Who can forget the schizophrenic bickering between Smeágol and Gollum — both performance captured by Serkis — in Lord of the Rings. Serkis also brought with him his VFX experience especially in weaving CGI into live human interaction.

When we last met Eddie Brock and Venom, both played by Tom Hardy, the two had formed an uneasy alliance. “It’s a joy to play two different parts of a psyche because Venom and Eddie are one for me,” says Hardy. “They are just differentiated by the fact that one is the monster and one is Eddie, but they are always contained within one individual.”

In the new film, that shaky marriage is starting to crumble. But Serkis sees it differently. “The film is a love story — but not the love story you might think,” explains Serkis. “It’s very much about the extraordinary relationship between symbiote and host.

“Any love affair has its pitfalls, its high points and low points; Venom and Eddie’s relationship absolutely causes problems and stress, and they have a near-hatred for each other. But they have to be with each other — they can’t live without each other. That’s companionship — love — the things that relationships are really about.”

Actor Tom Hardy had sought Serkis out as the possible director for the Venom sequel and Serkis believes that had something to do with the need for blending live capture with heavy CGI, “I think it was because he wanted a director who would be capable of safeguarding his performance, translating it into a visual-effects realm, with some degree of authority from experience with that.”

There’s no doubt that Serkis is one of the world’s best-known champions of film characters that blend CG with actors’ performances. Serkis’s experience with CG characters came through on the Venom film set. “I’ve spent a considerable amount of my life playing a character with two sides to his personality,” says Serkis. “I knew that this film would be about how to free up Tom to imagine Venom’s presence. We knew it would not be helpful for him to act opposite a man in a suit, because Venom is a symbiote, coming out of him.”

That is why, despite his many years of acting in performance capture, Serkis chose to animate Venom and Carnage with a more traditional CG animation approach. “We wanted to give Tom the freedom in his process to give the performance he wanted,” he says. Serkis and his team, however, did find ways to apply what he has learned from performance capture to this film. “We used it as a tool to find the physicality of the characters,” he adds.

For example, Spencer Cook, who oversaw the animation, says that footage of Hardy performing as Venom would inspire his team’s work. “That gives us some clues and indications of what we would want to take from Tom’s performance to put into Venom,” Cook explains. “We take those ideas and apply them to the Venom version — it’s an artistic interpretation of what Tom is doing.”

As he did on the first film, Hardy found that his best performance came from pre-recording Venom’s lines, which the sound team would then feed into his ear for Hardy to act against. “Tom’s process is driven mostly by audio,” says Serkis. “He builds a whole sound radio play before every scene.

“After rehearsing a scene, Tom would go off into a corner with a sound recorder and lay down a Venom track, which the sound guys would quickly cut into shape,” Serkis explains. “Then, we’d fit Tom with an earpiece, an ‘earwig,’ with the sound guys feeding Venom’s voice into his ear. That way, Tom can get his timing, he’s able to act against Venom, and he creates a physical presence for the character wherever he chooses to place his eyeline.”

“I have a radio transmitter that can play audio in and out, from up to 200 yards away,” says Patrick Anderson, the production’s playback sound technician — the sound engineer specifically responsible for the playback of Venom — whom Hardy calls his “partner” for the scenes in which he acts opposite Venom.

“I can feed him the Venom dialogue — and Tom will give me feedback, like ‘Take an extra beat before you feed me this line,’ or ‘Interrupt me with this line, mess with me’ — because Eddie can’t control the alien living inside of him. Having the cues set up individually, line by line, we’re able to make it free-flowing and chaotic, and a little more kinetic for Tom.”

Venom’s voice is enhanced by movie magic, but not by much — according to Anderson, Hardy’s performance brings the character most of the way there. “It’s pretty phenomenal how much of the character he can inherently give me,” says Anderson. “I’m just polishing the last 10% with a couple effects of my own — a little bit of pitch shifting to put it in that low monster register, some modulation to make it spacey sounding.”

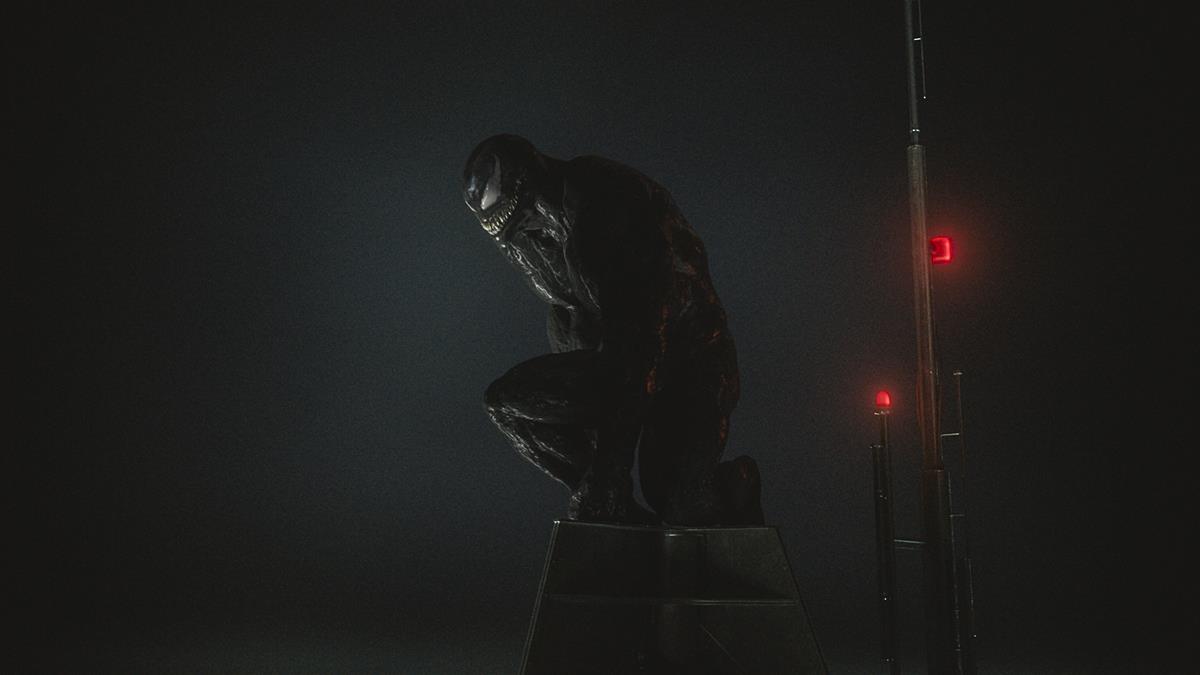

Bringing the characters to the screen also required a close collaboration with the film’s legendary director of photography, the three-time Oscar winner Robert Richardson. “Venom needs to be lit in a specific way, or you can’t see the articulation of his anatomy,” says Sheena Duggal, the film’s visual effects supervisor. “We found the best way to articulate the form of Venom is to use spectacular highlights that reflect off of his slimy surface.

“On set, we had a standalone bust that the stand-in could wear on his head and shoulders, and a bit of Venom material on a ball that we could hold in place of tentacles. With these, when Bob was lighting the shot, he could have a physical reference of what Venom would ultimately look like in the visual effects shot.”