One of the biggest surprises in streaming recently has been the overwhelming international success of Netflix series Baby Reindeer, receiving over 50 million views in its first month.

The series powerfully immerses the viewer in the desperate world of protagonist, Donny Dunn (portrayed by series creator/writer Richard Gadd), a struggling prop comic desperately searching for success and attention with his questionable act who ironically receives very unwanted attention from a troubled woman.

While working at his day job in a London bar, Donny gives a rather strange patron, Martha (Jessica Gunning), a free cup of tea and she responds to the small act of kindness by stalking Dunn with tens of thousands of emails, hundreds of hours of voicemails, more than 700 tweets and, eventually, physical confrontations.

So far, this could describe one of hundreds of more pedestrian stalker stories, but the factors that make Baby Reindeer so impactful come from the fact that it’s based in part on Gadd’s real-life experiences, so the stranger-than-fiction twists pull the viewer further into the visceral story than most shows even attempt.

Beyond the care that Gadd took with the scripts, plowing through hundreds of drafts for each of the seven episodes, the material was shot with the intention of forcing the viewer to look directly at events from which they might want to turn away.

“I think life is a comedy-drama,” Gadd explains. “Some of the darkest places I’ve been in, I’ve found giggles somehow. And some of the funniest places I’ve been in, including backstage at comedy clubs with other comedians, can be the most depressing places as well. I always think life is a mixture of light and shade. So, I wanted Baby Reindeer to be a blend of them both.”

Framing a Difficult Story

The series was broken down into two director/cinematographer teams, with Weronika Tofilska (His Dark Materials) directing the first four episodes and Krzysztof Trojnar (of music video, short film and commercial work previously) shooting and then Josephine Bornebusch (Bad Sisters) directing and Annika Summerson (Breeders) lensing the final three.

Trojnar, who had never shot a series before, worked with Tofilska prior to principal photography on the overall concept for the imagery.

“At the very early stage of prep,” the cinematographer recounts for GoldDerby’s Joyce Eng, “I listened to the audio track from the theater play” — the one-man show where Gadd first told the story he would later turn into Baby Reindeer — “and that had this very distinct, dynamic pace of Richard’s voiceover. And when I heard it, it kind of felt like you knew where you were going with it in a way that that’s going to be this intense fast pace.”

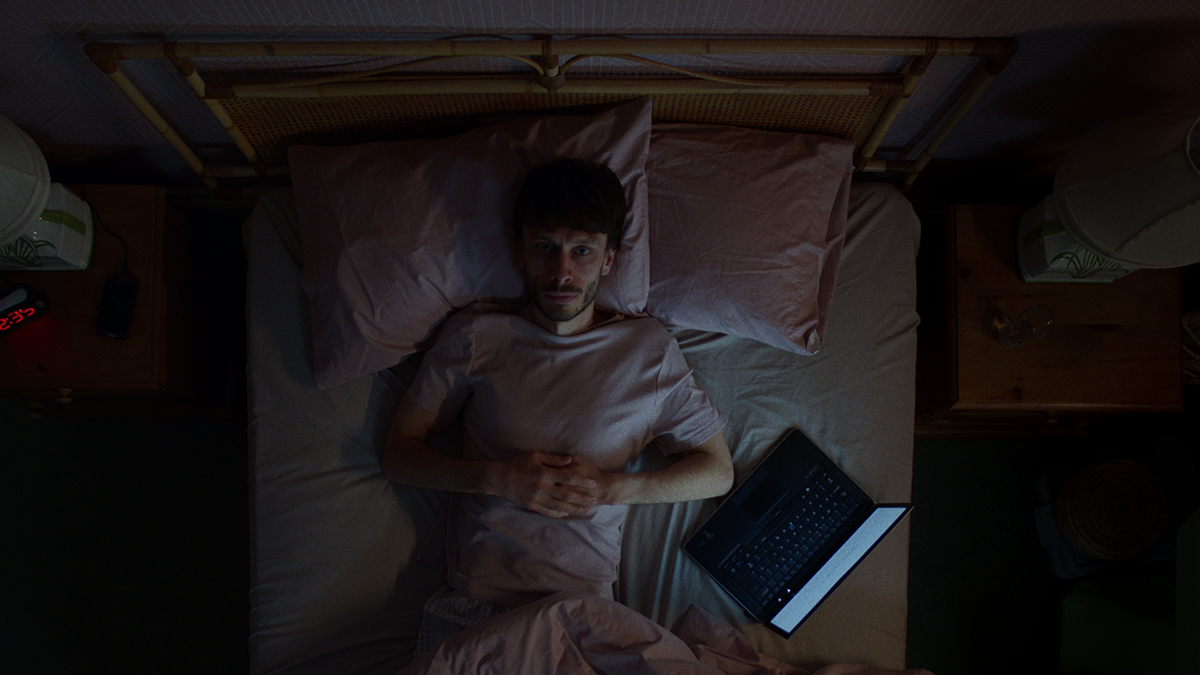

The cinematography, they decided, should be very much based on Donny’s point of view in every composition, and, within that construct, it should enhance the overarching sense of claustrophobia, even dread, that he feels.

Trojnar recalls this process to Ben Consoli of GoCreative. It was, he says, “definitely the character being stuck. Oppressed. In the sense of [the] environment [of] the world pressing down on the character or Martha sort of intruding the space and intruding his life.”

Trojnar placed his ARRI Alexa Mini LF (Large Format) camera up close to the characters, frequently invading their personal space. The sensor size (equivalent to 5-perf 65mm film) naturally requires longer focal length lenses to cover the same image area in the scene than would be needed for a traditional (equivalent to 4-perf 35mm film) cinema sensor.

As a matter of course, this results in a more compressed look between camera and subject as well as between subject and background. In other words: claustrophobic.

Taking this further, the framing was quite often very tight. They discussed placing Donny generally in the center of the frame, Trojnar explains to Kelle Long at motionpictures.org, “almost in the spotlight – something he is searching for in his life – and obviously also being sort of entrapped sometimes in [the] composition.”

Martha, he adds, becomes a “visual intruder in the sense of how close people are to Donny or how close the eyeline is to the camera. You almost feel their presence, and the camera is sort of between Donny and Martha.”

Later in the interview with Long he elaborates, “We used wide angle lenses so we could get close that’s abrasive in a way. It’s not something you would maybe do in a normal dialogue scene where you’re that close, but that gave this effect of intensity and intrusion that you almost can’t escape.”

“We paid a lot of attention and pushed really hard to always get that camera further in, the cinematographer tells GoCreative. “If it means moving something out of the way, moving the bar out of the way, we will do it to create that kind of intense experience and the intense effect on screen.”

Even for exteriors, he adds, shots were generally quite tight. Though the show was primarily shot in London, where it is set, there aren’t too many landmarks or buildings visible.

Even skies are generally excluded from the frame. “There is no sense of comfort or space,” he tells GoCreative, “apart from one scene when he’s in Edinburgh and it’s a flashback where everything feels a little bit more optimistic, little bit more hopeful. There is sky. There is more perspective,” although it should be no surprise that this wider perspective is short lived; soon we’re seeing a lot less sky again.

Episode Four

Even among those who have not yet watched all seven episodes of Baby Reindeer, many are aware that Donny’s dark story takes a significant downturn midway through as he starts to face events in his recent past which are arguably even more upsetting than the ordeal of Martha’s stalking.

These memories concern Darrien (Tom Goodman-Hill), an established comedy writer whose predatory behavior has profoundly affected Donny, even though the frazzled comic has not come to terms with what transpired during his drug-infused visits to this prospective mentor’s flat.

The whole episode starts…sort of optimistic,” he tells GoldDerby’s Eng. “Airy and there’s open space and there’s [the] atmosphere of hope and optimism and [it] ends much sort of tighter, more claustrophobic.”

“We actually used the widest range of lenses on the show in that apartment,” Trojnar explains to Long. “It’s not like he’s in front of the camera. He’s…almost touching the lens… It’s sort of entrapping but in this vacuous space. There’s something unsettling about the atmosphere as soon as Donny enters the apartment.”

It is here, the DP says, during a drug-addled moment where Donny is exploited by the comedy writer, that the technique of pushing the camera to invade Donny’s space is at its apex.

As Donny tries to escape the flat, its walls seem to stretch, isolating him further within the frame. The idea, which was conceived between Trojnar and production designer Debbie Burton, involved modifying the set to increase the character’s feeling of entrapment.

“We made the corridor double the length to what it usually was,” Trojnar tells Long. Burton’s team created a special corridor that was 40 feet long, as opposed to the actual 20-foot-long space we’ve seen to that point.

“When he’s in the corridor, suddenly this corridor gets so long and you kind of feeling lost when he takes LSD and there was definitely a feeling of like we wanted it to feel,” the cinematographer relates to Consoli of GoCreative.

“We installed a [RED KOMODO camera] on Richard’s head,” he tells Long, “so when he was running down the corridor looking down at his hands, that was actually filmed without me operating the camera. It was installed like a micro camera. He is trying to escape, and we get that tunnel vision kind of effect.”

The lighting also becomes its most expressionistic in this sequence. While it always took things beyond the naturalistic, here the cinematography did away with realism altogether.

At one point, he used a Mole Richardson “Mo Beam” he says, to bathe Donny in a totally unmotivated follow-spot — something he so desperate craves as a performer, which is illuminating him in ways he would never want.

Subsequently, Donny takes a vigorous shower back home and he starts to process what happened in that apartment. “We used this special lens that we installed inside the shower head,” the cinematographer tells Long.

“We asked the special effects department to make a … shower head that was hollow inside, then through the hole, we could put this special, very long, thin lens that is like a periscope lens. It’s called Optex Excellence. We used that so you almost have the perspective of the water falling down on Donny.”

This idea of tightly controlling the point of view, Trojnar recalls, extended to the most minute detail, even for what some might consider simple insert shots only there to convey information.

In the apartment as the drugs start to flow, there is a very tight close-up of some cocaine landing on a surface, and “it was so important that we see it from the top, we see it from Donny’s perspective, as you would…looking down in the counter.

“You would see it as a top shot,” he tells GoCreative. “You could just plunk the camera [down] and shoot it really fast without doing the whole rigging to achieve the top shot,” but it wouldn’t provide the sense of being Donny’s point-of-view onscreen.

So, despite some strong encouragement from producers to speed things up, Trojnar permitted his crew the time necessary to properly mount the camera in a way that would provide that sense of POV.

Color Theory in Action

Baby Reindeer was a particularly fascinating job for Senior Colorist Simon Bourne of Company 3 London.

The filmmakers, including Richard Gadd, who was very involved in every facet of the filmmaking, were after a grade that really made its own statement and a colorist who wasn’t afraid to push things beyond a safe sort of look, especially as Gadd’s Donny character descends into ever more frightening circumstances.

“All the colors had to be very bold,” Bourne recalls. “We definitely pulled away from a wide color palette. In fact, the palette is actually quite small. For example, there are almost no blues at all.”

His work started before shooting began with a show LUT that would bring the dailies partway into the realm of the intense, bold look that the final version would have without being so constraining as to limit what he could accomplish during the final grade.

Some people, he says, want to put too much into the LUT, which he sees as “seventy-five percent of the work. When we did final color, I graded through that LUT to pull more out of the shadows and fine-tune everything shot by shot. I’d sometimes blend the LUT, and I didn’t use it at all for some shots. I just built the look from scratch.”

Throughout the series a small number of colors stand out. Some greens, some yellows and red most of all. This naturally started with production and costume design and lighting, but which he enhanced in Filmlight Baselight through keying and drawing shapes around portions of the frame and either bringing out the red that was there or pushing some things that weren’t towards the red realm.

He did this frequently for scenes set in the pub where Donny works and in some of the other locations.

Nowhere was the red motif more pronounced than in the apartment in the much-discussed Episode Four in which Donny finds himself in a compromising position with another character.

“There were parts that were almost all red,” he says. “But we didn’t want it to just look like a red wash over everything because that would just look flat. So, we still built separation into the image.

“I’d key certain elements of the scene and just make them red. I’d build shapes around certain parts of the room that had a lot of red and make them a deeper red.

“The outside lights were yellow, so I isolated them in Baselight and made them red. The practical lamps were clean white, and I did the same.”

The process, he recounts, was very unusual for the degree to which he was encouraged to push the look and, of course, for the whole business of working in collaboration with both the creator and the subject of such a dark, revealing primarily true story.

“I don’t know anyone who’s ever gone through that,” he says. “It was unique for everybody, but he was very professional. He was heavily involved in everything — from the color to the edit to the music. He was very hands-on frame by frame by frame, but also very open to ideas.”

Audience Reaction

The filmmakers reportedly were confident that they had made a powerful series that explored Gadd’s story with an intensity and complexity not often seen in the medium, but they were still quite surprised by the enormous reaction. It is, after all, not designed to be a pleasant watch.

While it evokes empathy for characters whose behavior is by no means admirable, it is also essentially devoid of any character that an audience would instantly root for. In other words, it took great risks in trying to present something real, rather than soften the story into something designed merely to entertain.

“It was, like, crazy,” Gadd is quoted in the Daily Record newspaper. “I never expected it to sort of blow up like this,”

“We always thought about it as more of a niche project,” Trojnar elaborates for Eng. “We knew the script was good,” he notes to GoCreative, adding “we were kind of hoping it [would] find its audience, the size of the audience [was] definitely beyond our imagination or expectations.”

Why subscribe to The Angle?

Exclusive Insights: Get editorial roundups of the cutting-edge content that matters most.

Behind-the-Scenes Access: Peek behind the curtain with in-depth Q&As featuring industry experts and thought leaders.

Unparalleled Access: NAB Amplify is your digital hub for technology, trends, and insights unavailable anywhere else.

Join a community of professionals who are as passionate about the future of film, television, and digital storytelling as you are. Subscribe to The Angle today!