TL;DR

- Editor Yorgos Mavropsaridis, ACE discusses his longtime collaboration with director Yorgos Lanthimos on the multi-Oscar nominated “Poor Things.”

- Mavropsaridis explains how the dance scene on the cruiser became a microcosm for the whole film.

- He shares how he had to rip up the rule book for editing when they first met — and continues to do it on Lanthimos’s films to this day.

Editor Yorgos Mavropsaridis has collaborated with director Yorgos Lanthimos for more than 20 years and knew from the first moment they met that he had to ditch all the rules he had learned.

“The first question is ‘what is reality?’ he told Hayden Hillier Smith in an extensive interview at The Editing Podcast about the making of awards season favorite Poor Things.

“From the first collaboration I discerned that this is a guy who wants to say things in a different way, not the usual way we approach themes or character. For Poor Things I discovered many themes that existentially if you like, are about how easy it is to be in a society, which puts some rules on you.

For Lanthimos storytelling is not a didactic experience. “I want you to feel no, it’s more loose, it’s more open to interpretations and feelings,” says Yorgos Mavropsaridis who is Oscar nominated again following his work on previous Lanthimos drama The Favorite.

“All Lanthimos’ films desire a new kind of reality, which has certain rules how an individual can behave and questions whether this behavior is dictated by the character’s needs or by some external force. And of course, it’s the same with Bella Baxter.”

The lead character is played by Emma Stone in what has already been a BAFTA and SAG Award-winning performance.

Mavropsaridis says he still has to go against his instinctive approach to editing. “And I have to surprise myself as well, to create something new and not to repeat the same situations all the time.”

In all his previous films, they had used classical music mostly, but the director commissioned Jerskin Fendrix to compose the music for Poor Things months before the shooting started. Not the exact music as it was in the final film, but the general themes so they could have them in editorial after the first cut.

Lanthimos also used a lot of this music on set, having done this previously on The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017). “Different music was played back for [Stone] to somehow get inspired by the music — to have this surprise of — for the firsttime — seeing something.There was also music to set the inner rhythm or their external movements because Yorgos likesthe choreography of the actors — not only the facial expressions — and this way, the movement,internal or external, is influenced.”

Almost every scene uses an extremely wide-angle fisheye lens. Mavropsaridis explains there was no discussion with the director about when to use them.

“The usual pattern was a fisheye lens, or the 4mm lens with the iris mask, then a long take with movement combination, zoom in or out with tracking shot. Usually, my editing brain needs a reason to use them.

For example, the first time we used this 4mm lens was when Godwin Baxter went down the stairs, heard the piano playing, and then we cut to him. He looks at her and smiles. At that moment, I thought, “Okay, that 4mm lens would be a nice point of view from this strange man.’ Then the next time was when Max comes in, Bella runs and embraces Godwin Baxter like a baby. I thought it was funny: a grown-up woman being like a baby, maybe seeing it through Max’s eyes for the first time — this strange situation, there are always small reasons. Subliminally they might say something to a viewer.”

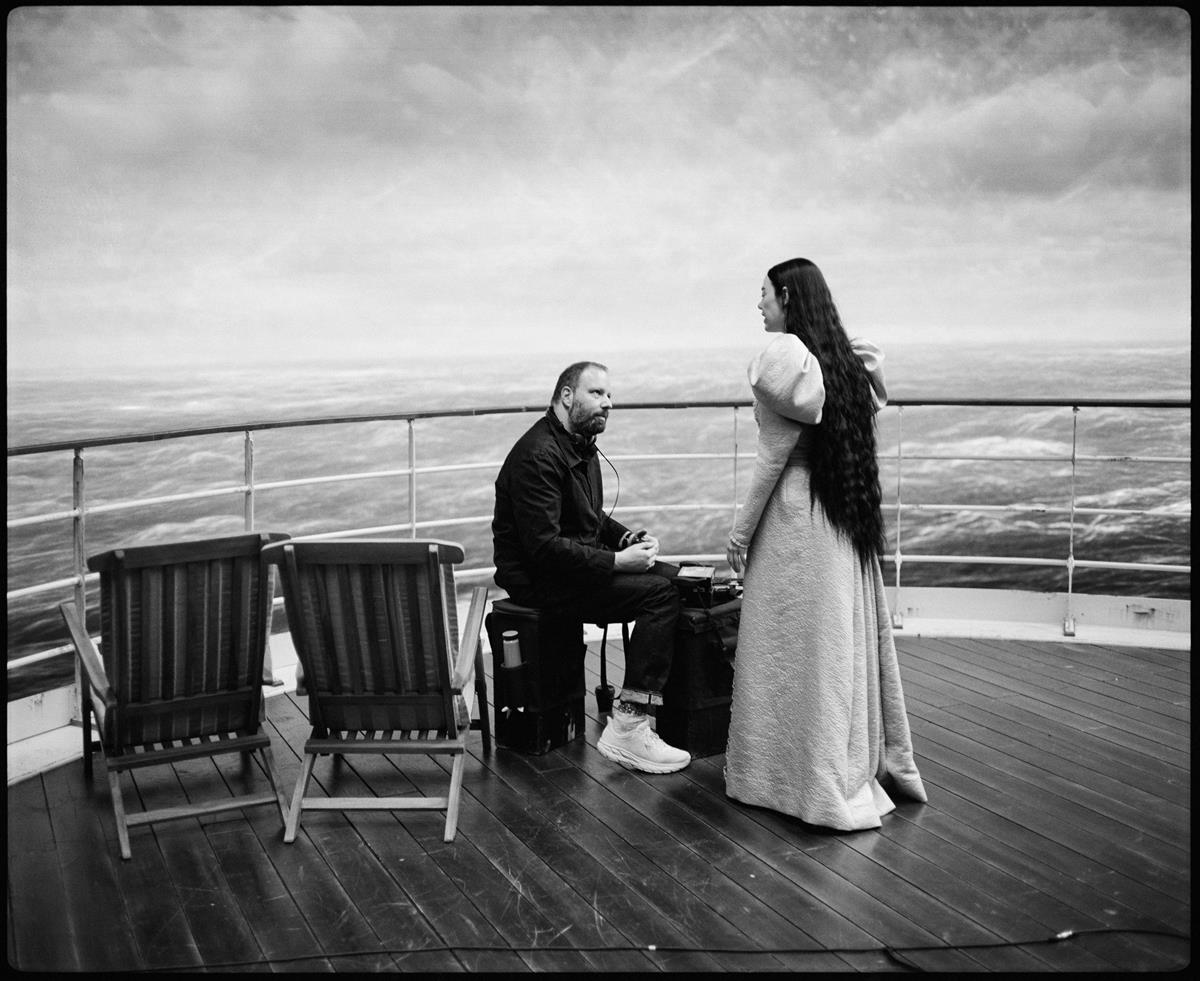

Another example is when they are in the cruiser and Bella Baxter says to Duncan Wedderburn, “You’re in my sun!” so Mavropsaridis cuts to the 4mm lens when he throws the books away, “just to punctuate the situation. Different reasons all the time.”

It was the director’s idea from the beginning to have the first part of the film be a kind of homage to the old Gothic films shot in black and white. They then break that by introducing the color picture in the beginning.

“It was broken in an interesting way when Godwin Baxter recites the story of Victoria Blessington: how he found her, being pregnant with the baby, was shot in color,” Mavropsaridis says.

“There was a good juxtaposition between black and white in the office narration and the color of her suicide and the discovery of her body, which also breaks interestingly the time continuum between the two situations that are kept continuous with his narrating tale. Then the rest of the film, after her leaving London, was in extreme color and also in different hues of color. For example, the first part in Lisbon was shot with color negative.”

The scene where Bella dances without a care in the world was edited “incorrectly” by Mavropsaridis initially. He felt the choreography should remain intact when in fact it had to be awkward. The creative idea was that the dance was “a microcosm of the big world of the film.”

“Of course, it was very nice to see her in a situation with other dancers, and I thought it was nice to keep this situation with the other people dancing around her that was so funny. But this was not what it was supposed to be,” he says.

“Bella is about 16 years old at that time. She sees people dancing for the first time, and the particular music excites her and she wants to dance, but she hasn’t danced before, her movements are rough and awkward, but she doesn’t care about what other people would think. And we didn’t have to care if her movements were choreographed or ‘correct.’ It had to be spontaneous,” he continues.

“Everybody wants to control her, so the main part of the choreography we had to keep were these movements: When Duncan puts his arm around her, trying to manipulate it, and she reacts, trying to free herself. This dance scene is a microcosm of the whole life situation.”

Once they had reached this point where everything was in place the cut was three-and-a-half hours. Then they had to deconstruct the whole thing.

“We have constructed it. Now let’s take it apart and see what we can do to try this or that. He’s very precise in what he wants, but usually, the edit has to improvise on how to achieve it,” Mavropsaridis says.

“He doesn’t say much, but since we’ve edited together for almost 25 years now, I know what he means, and I know which way I have to tackle it. I have a lot of freedom from him to try things, even if they were not discussed. If I have an inspiration in the middle of the night, I will do it,” he continues.

“Maybe it works, maybe it doesn’t. After many trials and errors, many hours, and many films together, we have reached a very understanding way of working. I believe that Poor Things was an easier film to edit.”

A discussion at the dinner table about marrying Bella includes flash forwards and flashbacks. This was composed in the edit to cut length and keep the story moving, Mavropsaridis told Steve Hullfish on the Art of the Cut podcast.

“It is a method that we developed on the film we did together, Dogtooth because Yorgos likes to shoot his film in continuity. He doesn’t edit during the shoot so in editorial we felt that this big scene with a lot of discussion going on needed to be compressed.”

Typically, editor and director will have a few issues that can only be resolved in the edit, but there is now a telepathic connection between the pair that is only the result of like minds working together for so long.

“There was a problem about a scene on the cruise ship,” he told CinemaEditor magazine. “While Yorgos was emailing me I sent over my solution and he said, ‘That is exactly what I have in mind.’ I have reached a point of being able to understand his thoughts without talking to him. After so many years I know what the small things are that bother him and what he tries to achieve. At the same time, he has helped me to overcome my laziness of the mind, so it is now easy to me to throw a scene out and do it a different way.

“I always have in my mind Lanthimos’ own phrase — ‘Is that all we can do?’ So I have to prove each time we can do more and better.”