TL;DR

- Deep fake technology is starting to be used in documentaries and for advocacy work.

- Several filmmakers and human rights advocates told the International Documentary Association that they believe the generative AI can be used responsibly to help shield subjects’ identities and to creatively (and responsibly) tell true stories.

- They also say that disclosure and watermarking are both crucial to building audience trust in synthetic media and avoiding the trap of “context collapse,” when content is excerpted from its point of origin.

Most of the time when you hear about deep fakes in the news, the reason is negative or at least controversial.

“Synthetic media is at the center of many of the most pressing conversations about the social and political uses of emerging tech,” International Documentary Association moderator Joshua Glick said in his introduction to a panel discussing the ethics of using deep fakes and generative for non-fiction media. Watch the full discussion, below.

GUIDELINES FOR GOOD

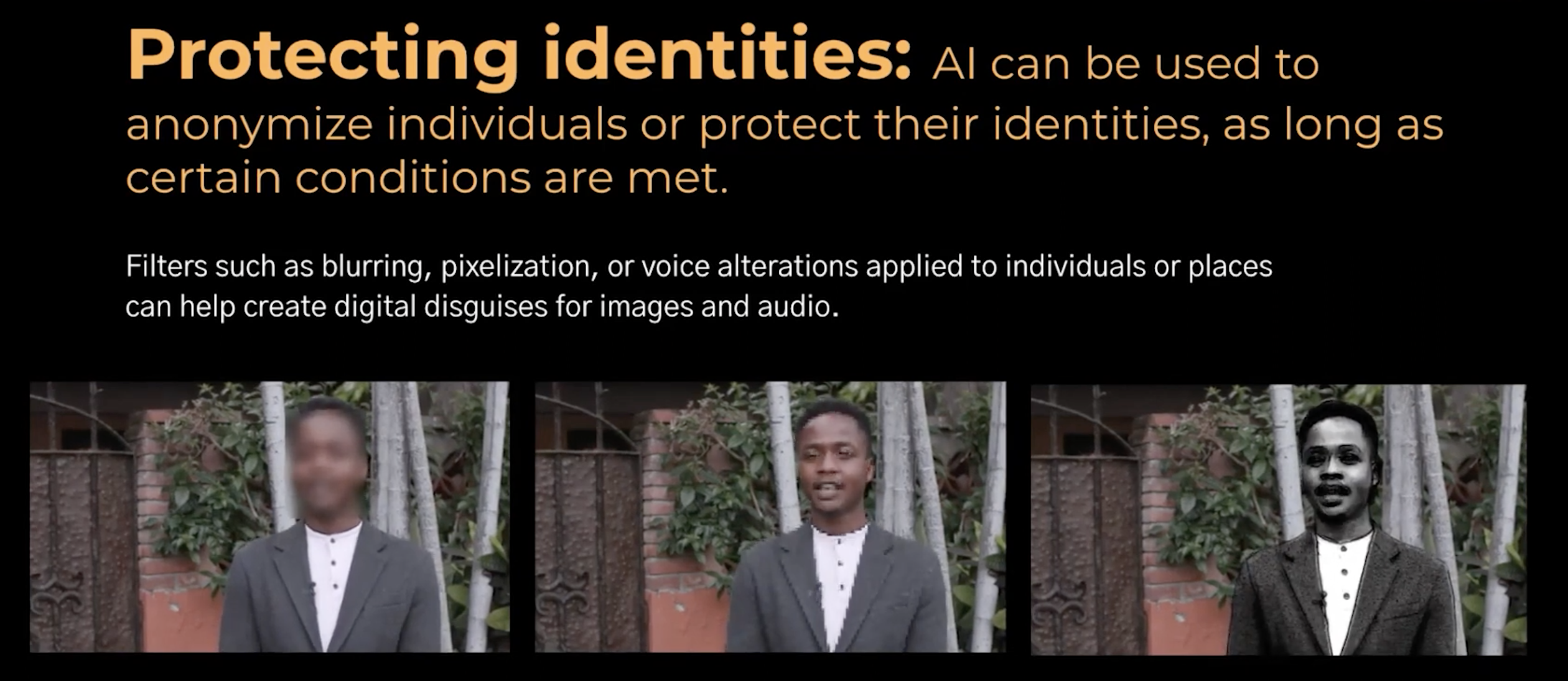

“These tools can be very useful, but only following certain guidelines around dignity, transparency, and consent of the individuals,” human rights lawyer and Witness documentarian Raquel Vazquez Llorente explained. “So any process that uses AI for identity protection, shall always have careful human curation and oversight along with a deep understanding of the community and the audience it serves.”

Although it may be counterintuitive at first, Vazquez Llorente says deep fake tools can be deployed in “ways that could humanize the subject,” in addition to lowering the lift for filmmakers who want to protect them.

“There was also something… very powerful about this capacity to reclaim this technology. And we strongly believe that technology itself is not the problem. It’s the application. It’s the cultural conditions around the way that it’s able to be used,” explains filmmaker Sophie Comption.

Also, Violeta Ayala told the audience, “I ask you to not wait until a government will legislate these things because we can even trust those governments and how far they’re gonna go. So we need to start thinking and talking and put these ideas and these questions and these possible guidelines that maybe then we can push forward and understand that we’re not coming here to say no, no, no, no, I don’t like these.”

Additionally, Vazquez Llorente says, they advocate for “disclosing of the editing and the manipulation.” Meaning “any AI output, we firmly believe it should be clearly labeled and watermark considered, for instance, including metadata, or invisible fingerprints that allow us to track the provenance of media.”

For example, “voice cloning is one of those that is very difficult for an audience to tell if there’s been any kind of a manipulation. So how are we disclosing that modification to the audience?”

They must, Vazquez Llorente says, fight the problem of “context collapse,” which is common across the internet.

“We also have a responsibility to educate the audience… so that they will be more media literate going forward, and will understand its sort of uses when they encounter it,” says Reuben Hamlyn.

CHALLENGES

“The use of AI to create or edit media should never undermine the credibility, the safety or the content that human rights organizations and journalists and the commutation groups are capturing,” says Vazquez Llorente.

Unfortunately, she admits, “the advent of synthetic media has made it easier to dismiss real footage.”

Hamlyn agrees: “We’re at a time where synthetic media technologies are dissolving trust in imagery. And as documentary filmmakers, you know, trust in the imagery is the foundation of our medium.”

That’s why disclosure is so crucial, but that can create challenges in and of itself. “You also run up against this issue where the disclosure [is] sort of complex and it can disrupt the sort of the emotional process of the film,” he suggests.

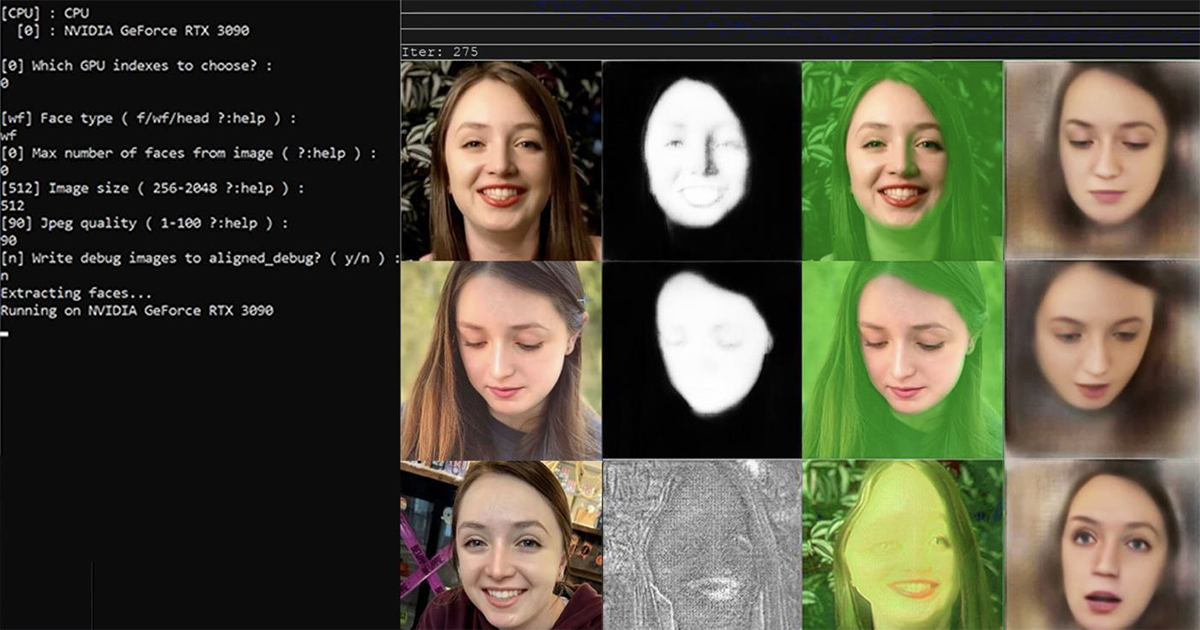

Then there’s the problem of inadvertently further “dehumanizing” subjects and using AI-generated “results that often enhance social, racial and gender biases and also produce visceral errors, right that sometimes they pick the form buddies. So it’s important also to keep in mind, I will preserve the dignity of the people we are trying to represent and that we are editing with AI. And the final question is, does the reformatting the resulting footage as I was mentioning, inadvertently, or directly reinforce these biases that already exist because of the data sets that have been fed into the generative AI models?”

Creators also must consider “whether the masking technique could be reversed and reveal the … real identity of an individual or their image,” she advises.

HOW TO USE IT

Identity Protection: We’ve all seen documentaries when witnesses share information from the shadows with their voices digitally altered. Generative AI could make the both tropes passé very soon by instead creating a new face for interviewees that would show their expressions while hiding their true identity, or utilize voice cloning to retain inflection while shielding their vocal signature.

Creative Advocacy and CTAs: PSAs might not need to feature real people or even actors.

Visualizing Testimonies: When done right, viewers may be able to use these tools to better understand and empathize with the plight of victims.

Repurposing Footage: “You may capture in footage for certain purposes today, but then in few years time, maybe revisit or reclaim for other different purposes,” Vazquez Llorente suggests, explaining that you may need to anonymize participants for the new context, even if they agreed to be shown in the first.