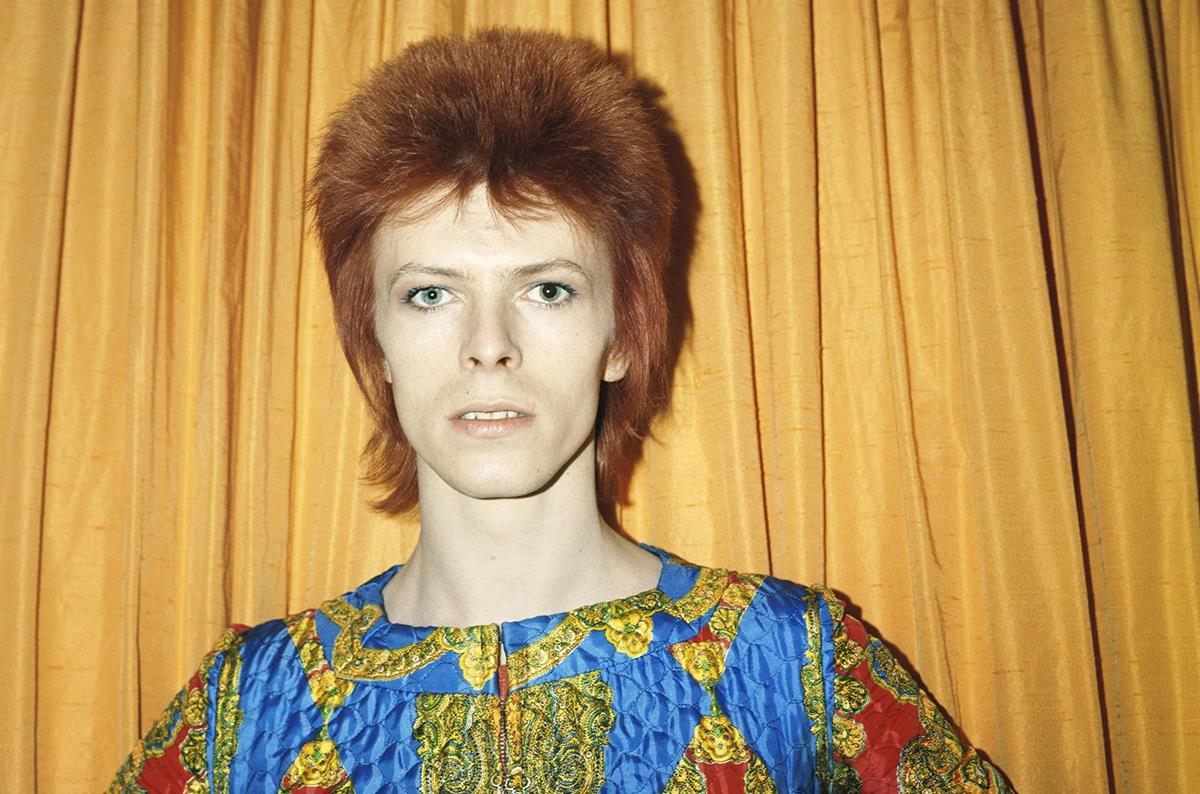

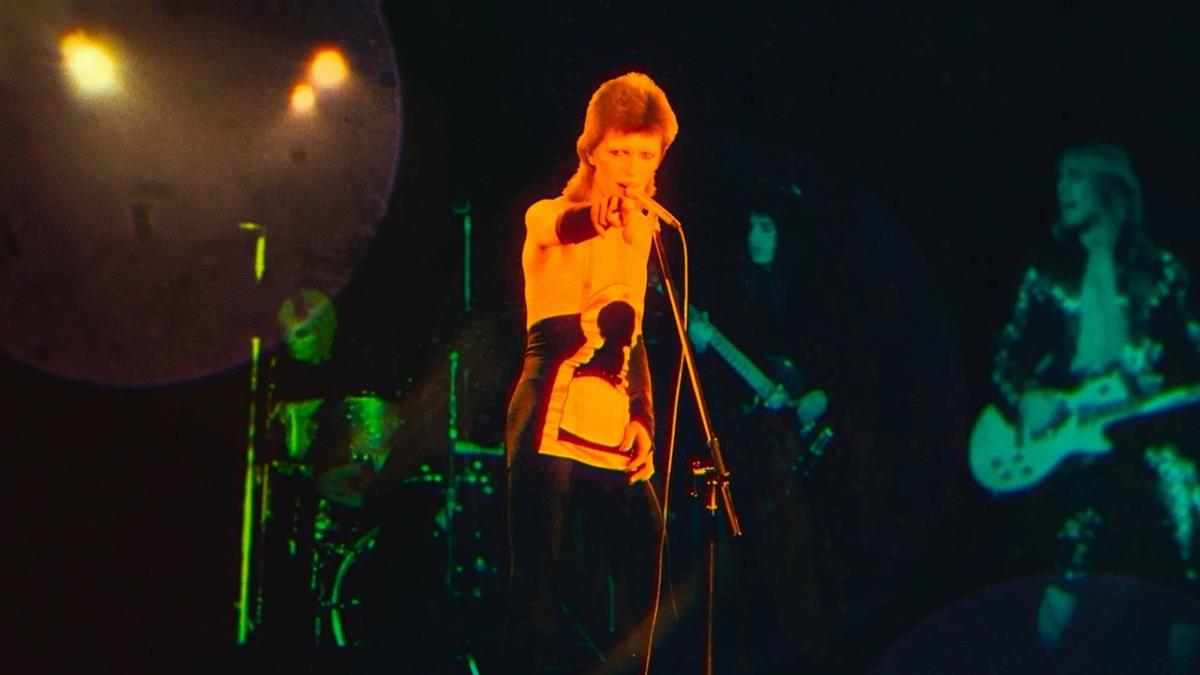

Brett Morgen’s documentary feature Moonage Daydream, Bill Desowitz writes in IndieWire, is “a kaleidoscopic, mind-blowing journey about the chameleon of rock, built around David Bowie as narrator (culled from pre-existing material), performer, and philosopher about the transience of life and the promise of the new millennium.”

Describing what it is that Morgen has created is the first hurdle for the reviewer. New York Times culture reporter Melena Ryzik gamely tries, writing, “Morgen’s opus about Bowie is billed not as a traditional documentary but as an immersive experience. It’s equal parts psychedelic and philosophical — a corkscrew into Bowie’s carefully constructed personae, assembled entirely from archival footage and audio, some of it rare and never broadcast before.”

READ MORE: A Filmmaker Explores David Bowie’s Life and Finds Clarity About His Own (The New York Times)

Esquire UK’s Alex Bilmes turns a fan’s eye to the new film. “Now comes something more daring, and cinematic, and still more successful: Moonage Daydream, an attempt to capture on film some of the otherworldly appeal of the extraordinary David Bowie,” he writes.

“Sanctioned by the Bowie estate, which apparently gave Morgen access to five million pieces of archived material, Moonage Daydream does not seek to be definitive, or exhaustive. It’s a meditation on Bowie’s brilliance, an immersion in his aesthetic, and a portrait of the artist as existentialist — a searching, compulsively creative spirit.”

READ MORE: ‘Moonage Daydream’ is the Greatest Rock Movie of the Decade (Esquire)

But the movie’s story can’t be told without Brett Morgen, the director and eventual super-fan. He told IndieWire’s Desowitz his goals for Moonage Daydream and described how they took form. “I was hoping to create a theme park ride [in IMAX] around my favorite musical artist, something that would be intimate and sublime and experiential,” Morgen recounts.

“But the film became something much deeper and richer, which I didn’t expect to encounter,” he adds, “because prior to starting the film, I only listened to David’s music — I hadn’t really listened to his interviews. So the film became more life affirming than I anticipated.”

READ MORE: ‘Moonage Daydream’: How Brett Morgen Cut His Mind-Blowing David Bowie Documentary (IndieWire)

Venerable critic Hilton Als, from The New Yorker, isn’t necessarily taken in by all the kaleidoscopic visuals: “Bowie gave a damn. But his love of the rogue spirit in others, his collaborative urges, his paternal instincts — all of it wrapped in his own particular freak flag — aren’t much in evidence in Brett Morgen’s new documentary, Moonage Daydream,which instead fills the screen with visual bombast.”

As an artist who tried to align himself with others who, “like him, had broken down the walls between “real” art and the pop world,” Bowie’s career was constantly full of evolution and experimentation, Als contends. Yet despite the use of fast cuts, “Moonage Daydream is strangely inert, with only occasional flashes of Bowie’s personality, his fascinating combination of British formality, eccentricity, and wit. Morgen’s daydream is that he’s the only person who truly gets Bowie, and foremost among the things he supposedly understands is how alienated Bowie was, as much by nature as by inclination.”

He quotes Ellen Willis, who questioned Bowie’s authenticity in a 1972 piece for The New Yorker. “Bowie doesn’t seem quite real,” she wrote. “Real to me, that is — which in rock and roll is the only fantasy that counts.” But Als argues that, actually, “Bowie’s reality was always there, hiding in plain sight. To my mind, it wasn’t coldness or alienation of the kind that seems to interest Morgen but a pervasive loneliness that was at the heart of so much of his music, and perhaps the reason that he kept reaching out to, or defending, all those other artists and listeners who knew more than a little about difference.”

READ MORE: A Portrait of David Bowie as an Alienated Artist (The New Yorker)

In an interview for Filmmaker Magazine, Tiffany Pritchard sits down with Morgen to discuss his unconventional approach. “The first 20 minutes you are not supposed to understand [the film], it’s supposed to wash over you and be a mystery,” Morgen tells Pritchard. “Once you get past these 20 minutes, you can relax.”

Morgen, who says he’s never had interference from artists when it came to music and generally doesn’t work with a music supervisor, “had a bit of fun with the audience” for those first 20 minutes: “I call it a jukebox musical — the film starts with a playlist that, in my interpretation, included songs that relate to transience, chaos and fluidity. But really, I don’t know about music more than anyone else. These are simply music tracks from my playlists.”

So what inspired the filmmaker’s intimate montage of Bowie? “My number one rule for this film was ‘no facts and no learned information.’ The best way to experience Bowie is to not explain but to just succumb. And so the film was put together very spontaneously, with a lot of techniques that Bowie employed.

“I wanted to arrive at something different, totally experiential. We all have our own Bowie — I tried to make the film so that everyone can find their own Bowie.”

READ MORE: “I Tried to Make the Film So Everyone Can Find Their Own Bowie”: Brett Morgen on Moonage Daydream (Filmmaker Magazine)

Carole Horst’s interview with Morgen for Variety had the director questioning why he had even attempted documenting an artist with an already-published cache of 27 books solely about him. But he dismissed them just as quickly. “…So if you want to know that stuff, you can go do that. But what can I offer that you can’t get from those books? That’s generally the first question as I approach it: What can I offer in this space of cinema?”

Morgen blew through his initial timeline of 68 weeks to complete Moonage Daydream, with the project eventually spanning five years, albeit with a pandemic stuck somewhere in the middle. He explained his evolving timeline to Horst. “After trawling through the material for two years, a through-line definitely emerged related to chaos and transience, and which was a little different than change. I think people think of change as the through line of David — you know, cha-cha-changes. But it’s more on a spiritual level, like transience,” he said.

“I spent a year working on the script, which [involved] collating his interviews into these sort of more philosophical endeavors and creating a playlists that would play out a little bit like a jukebox musical, so that the songs were all chosen for the way they captured him in those particular moments, but more importantly because they had some thread back to the through-line of the film about transience. So that’s how I kind of was able to weave the stitch the narrative together.”

READ MORE: David Bowie Doc Director Brett Morgen Paints a Portrait of an Artist in ‘Moonage Daydream’ (Variety)

AnOther’s Carmen Gray reports that, while sorting through the materials from Bowie’s estate, Morgen came to appreciate the star “as someone able to embrace change on a deeper, spiritual level, and navigate the anxiety and chaos of our times.”

Calling Bowie a “21st-century prophet,” Morgen imbues the artist with nearly mystical powers. “He was very attuned, and could hear things that we couldn’t hear, and see things that we couldn’t see,” he tells Gray.

“We are living in a digital world inundated with information, and Bowie was talking about this before there was the internet. And the issues that have risen to the forefront of mainstream culture finally after 50 years with gender fluidity, he was talking about 50 years ago.”

When he finally reached the estate, Morgen was faced with the fabled persona Bowie had crafted around himself. But this didn’t seem to faze the director, as Gray notes. “It’s critical not to be intimidated by either the subject or the amount of material,” Morgen said, describing the process as a “murder scene,” where some raw material naturally stands out, as if dye had been applied to reveal blood.

Regardless, the predicted 68-week production ended up taking five years. “The freedom to work until he feels truly done is essential to Morgen — something he learned the hard way,” Gray writes.

“I decided I would never under any circumstances do that again,” Morgen insists. “When a film comes out and isn’t ready, it becomes a product.”

READ MORE: Five Years in the Making, the New David Bowie Doc Is Finally Here (AnOther)

Morgen described the challenges he encountered while making what he referred to as “The David Bowie Experience” in an interview with Tom White for Documentary Magazine following the UK premiere of Moonage Daydream at the Sheffield Doc/Fest.

Creating a structure for the theatrical cinematic experience he envisioned, as opposed to a more conventional, linear documentary, was particularly vexing to Morgen, as he recounted to White. His usual approach of applying “a very rigorous aesthetic” to his films well before entering the edit bay, wasn’t working.

“Every film I’ve done has been written before I’ve gone into the editing room, and the edits don’t deviate much from the scripts,” he said. But after reviewing footage for two solid years, “and telling my investors that I was going to do this crazy Laserium-like experience,” he sat down to write an experience only to find that he didn’t know how.

“I am very linear in my thinking,” Morgen explains. “Jane, Montage of Heck and The Kid Stays in the Picture are very much scripted like dramatic films, with cause-and-effect narratives and three acts.

“With Moonage Daydream, I struggled mightily for eight months. I had a tremendous amount of self-doubt. I had exhausted most of our budget by that point before I had started editing, just getting all of this material ingested. And I didn’t know how to do it.”

Initially, Morgen attempted to cut the first space scene that helps bookend the film. “It is like a template of what the film should be, but I didn’t know how to go anywhere from there,” he said. “I realized that the film was going to require more structure. And as I went through the materials, I was able to establish a throughline of action related to transience and transcendence, or some variation thereof.”

Channeling chaos and fragmentation as Bowie’s throughline allowed Morgen to connect many of the elements that helped define the iconic artist. “The cut-up process that he borrowed from William Burroughs is involved in that. One can argue that his belief in no absolutes and his ability to stay in the now, in the moment — I had falsely thought that David created these different characters that defined him, and as you notice in the film, it’s not about characters.

Morgen began to perceive Bowie’s life and career “as more like a series of movements, like Picasso—these periods where you would just see these dramatic shifts. Once I landed on this idea of transience as the through line, and it was not going to be biographical, per se, I was still stuck. I pulled a trick out of Bowie’s book, which is, Get out of your own environment.”

With that in mind, Morgen traveled to Los Angeles by train, vowing that he wouldn’t return until he cracked the script. “Twenty-four hours later I had the script that the film is based on. And the way I arrived there was, I decided to play a game. And I said, OK, let’s pick three songs from each album that relate to these themes and see what that looks like. And I was like, Oh, wow, that could be the movie. And it covers the whole career. It doesn’t just lean towards the hits. And then it became a question of reorganizing and restructuring that playlist and using that as the foundational blueprint for the film. And that inherently was driving me towards a more linear path.”

Moonage Daydream, Morgen insists, was designed to be a film about the viewer, not David Bowie, “attempting to use the techniques that Bowie employed, and to make a film that’s more felt than learned.

“The idea was that it wasn’t so much about humanizing David but as inviting the audience, as one does with every film. To project themselves, project their own story. My hope was that people would be meditating on their own lives throughout the film. And they can leave the theater thinking about their lives, not David’s life. And the hope was that what he’s talking about would resonate with almost anyone, because it isn’t specific to the music industry or even to the creative process. This is about life. There are words of wisdom that emanate from David that are so applicable to enhancing our day-to-day living.”

READ MORE: ‘Moonage Daydream’: Brett Morgen Presents The David Bowie Experience (Documentary Magazine)

Variety chief film critic Owen Gleiberman reviews the film in what seems to be a more matter-of-fact manner which, for the non-fan, is more helpful as a guide to whether you watch it or not. “Moonage Daydream is no hippie-dippy daydream,” he writes.

“Bowie narrates the film, with Morgen splicing together interview clips so that Bowie is basically ruminating on who and where he was at any given moment. He’s a magician who’s willing to reveal his tricks, and also a happy doomsday philosopher; describing the cultural fragmentation that set in during the ‘70s, he says he embraced the idea that ‘Everything is rubbish, and all rubbish is wonderful.’ ”

He continues, “That meshes nicely with Morgen’s filmmaking, which is a form of apocalyptic montage. It’s the school of pop-drenched free association that, yes, we think of as music video, but Morgen evokes the most dangerous and visionary landmarks of the form, like Natural Born Killers and Godard’s The Image Book and the 28-minute film that started it all — Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising.”

But what are we, as fans, meant to take away from the movie? Morgen had intentions for that, as he relayed to the audience at the Sheffield Documentary Festival. “I tried to design the film in a way that invites everyone to find their own Bowie,” he said. “The less you put out there the more you invite the audience to project their own ideas on it. In the film I try to do that by withholding biographical information. By just giving you broad strokes, it allows you to more closely identify with the material.”

READ MORE: Behind the Scenes: Moonage Daydream (IBC365)

Tim Lewis from The Guardian asked Morgen if he agreed with one fan’s response to the film, which had been posted on Twitter: “Drugs would be redundant. It’s mind-bending.”

Morgen responded, “I’m not sure I agree wholeheartedly with that statement, but I don’t want to be irresponsible. It’s a maximalist film, it’s definitely kaleidoscopic and it really embraces the idea of being a piece of immersive entertainment.”

But his inspiration for the project “was probably more my experiences at the planetarium [at Griffith Observatory, Los Angeles] seeing the Pink Floyd Laserium and going on those inside-theme-park rides at Disneyland than any specific movie,” he said, before adding, “But you know, I’ve been to Disneyland on acid and it’s kind of awesome, so…”

READ MORE: Brett Morgen on his David Bowie film: ‘Moonage Daydream is maximalist, it’s kaleidoscopic’ (The Guardian)

Mashable’s Kristy Puchko compares Moonage Daydream to the recent stream of popular “immersive” touring art installations. “You know the emerging trend of immersive art exhibits?” she asks. “The paintings of the likes of van Gogh and Klimt are re-imagined in a 3D space, perfect for Instagram selfies. Glittering and in motion, their long-ago brush strokes become interactive as they are projected across massive walls, surrounding the viewer in masterpieces come alive. This is what Morgen seems to strive for with Moonage Daydream, and I do admire his apparent ambition.”

Commenting on the film’s limited release in IMAX theaters, Puchko says, “The cosmic candy-colored treatments of Bowie’s archival footage is meant to be displayed massively, swirling before the audience as if to envelop them.

“The soundscape, crashing waves of Bowie’s interviews and music with a rat-a-tat-tat of sputtering gears might well intoxicate, urging you away from the concreteness of common bio docs in favor of something purposefully more ethereal and inexplicable.”

But as the film goes on, Puchko notes how Morgen steers towards “moody re-enactments, muddled montages, and a barrage of film clips, ranging from Nosferatu and The Wizard of Oz to Labyrinth. One might extrapolate that Morgen is connecting Bowie’s influences to the artist’s own works to illustrate a continuum of imagination and daring,” she says.

READ MORE: ‘Moonage Daydream’ review: David Bowie remembered if not revealed in daring documentary (Mashable)

But let’s go back to Gleiberman, as his previous inclusion was a mere prelude to his ultimate fan-boy stance: “More than ever, our identities seem liquid, and David Bowie was the avatar of that. Yet in Moonage Daydream, the more you listen to and look at Bowie in all those different guises, the more you see just one man: not a chameleon but a searcher,” he enthuses. “The changes he went through as if he were surfing them are the changes that life puts all of us through. Life, says Moonage Daydream, is a lot like rock ‘n’ roll. It exists in the moment, and that moment will soon be destroyed. But it’s beautiful while it lasts.”